Category of Astronomical Heritage: tangible immovable

Seeberg Observatory, Gotha, Germany: General Description

Description

Geographical position

Gotha Seeberg Observatory, Gotha, Thuringia, Germany, Elevation 406m above mean sea level.

(The transit instrument had the coordinates, also used as zero point for surveying: 50° 56′ 05″ N, 10° 43′ 51″ E)

New Gotha observatory: Jägerstraße 7, 99867 Gotha

Location

Seeberg observatory

- Lat. 50° 56′ 1.5″ N, long. 10° 43′ 41.5″ E, elevation 406m above mean sea level.

New Gotha observatory

- Lat. 50° 56′ 34.512″ N, long. 10° 42′ 30.996″ E, elevation 318.3m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code

279

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage

Private Observatory in Castle Friedenstein in Gotha

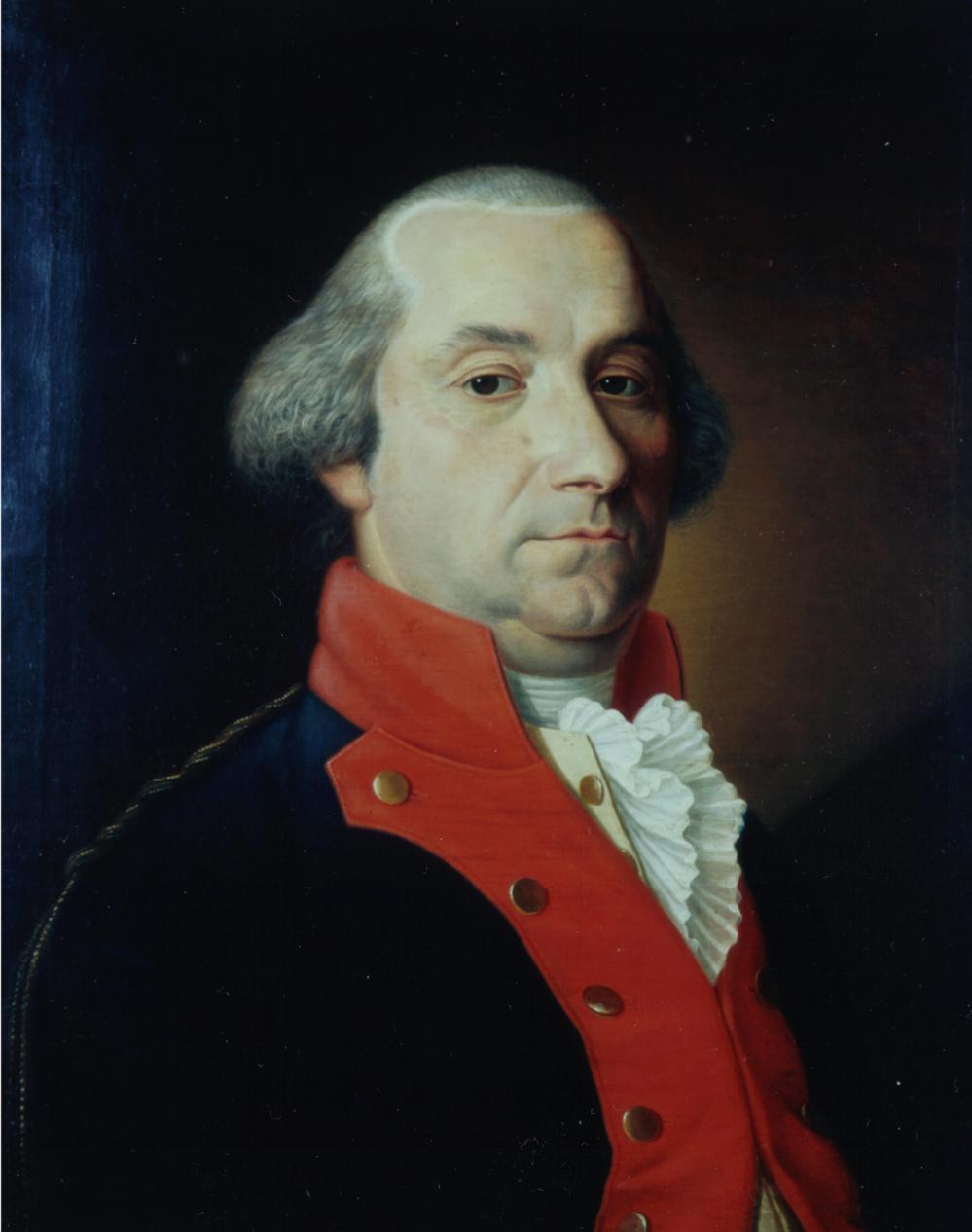

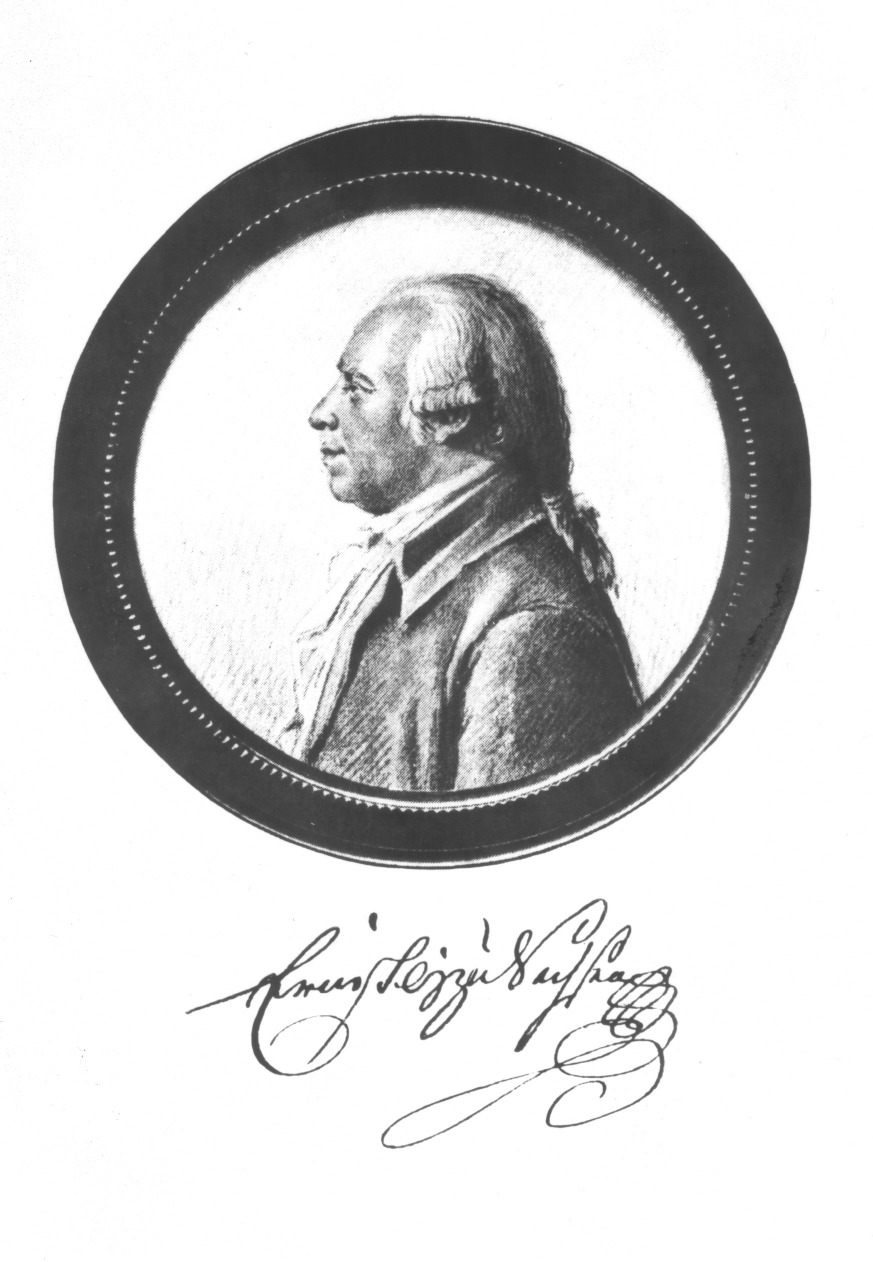

Ernest II, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg (1745-1804) used first his castle Friedenstein in Gotha as a private observatory.

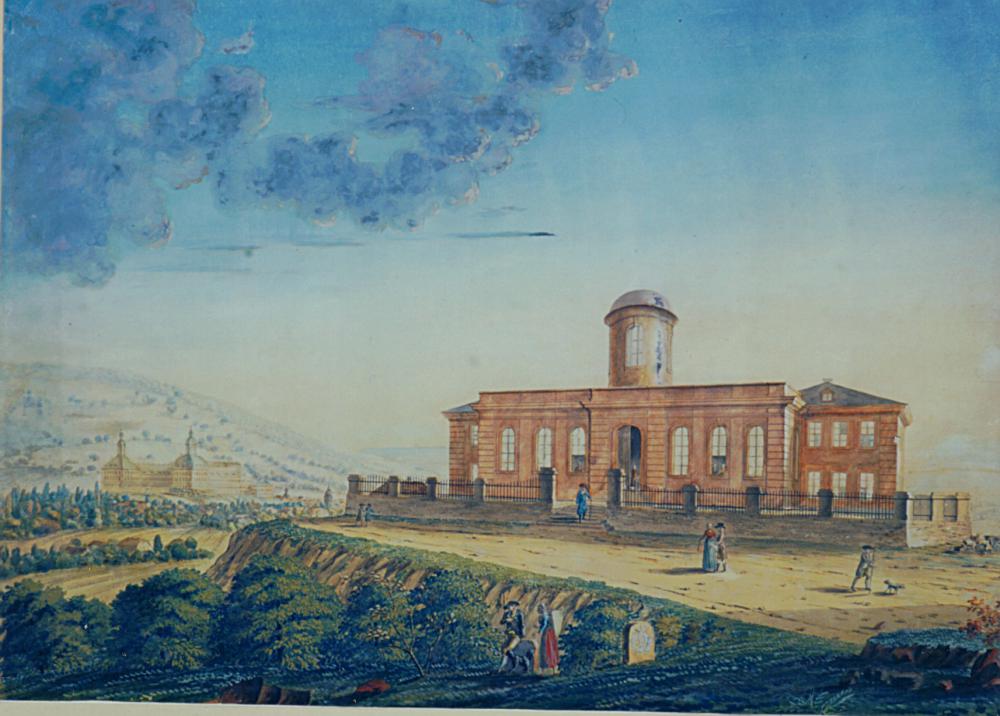

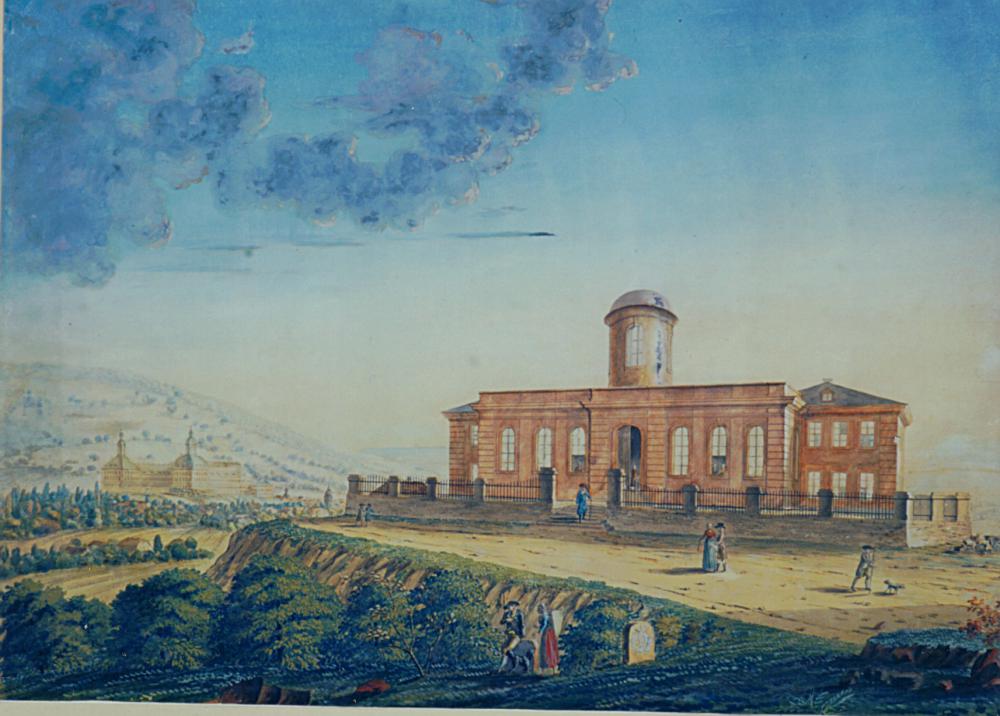

Fig. 0. Seeberg observatory Gotha, around 1800, to the left the Ducal Castle Friedenstein of the early Baroque (1643-1654), built by Ernst I (1601-1675), Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg (aquarelle, Forschungs- und Landesbibliothek Gotha, Wikipedia)

Seeberg Observatory Gotha (1788)

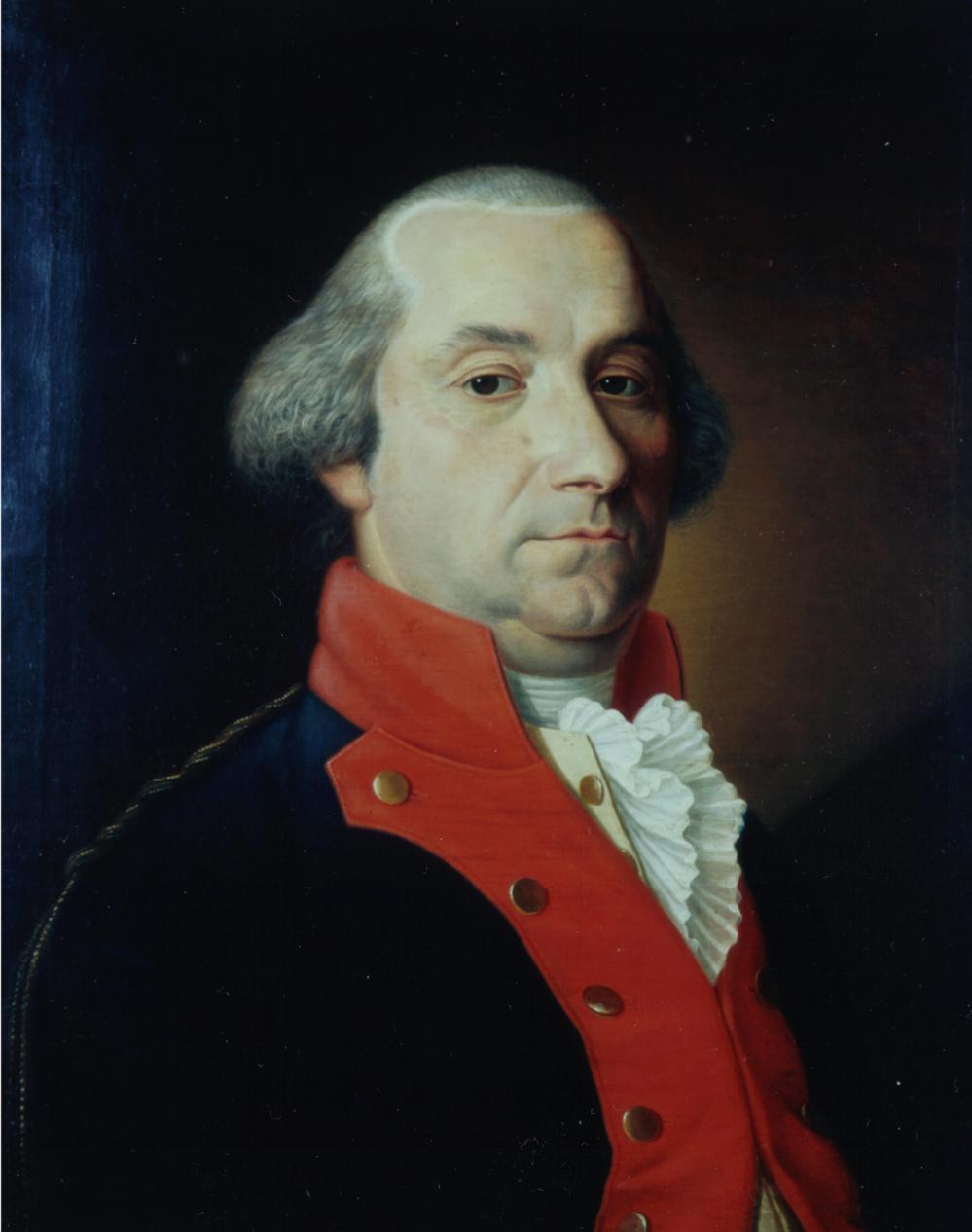

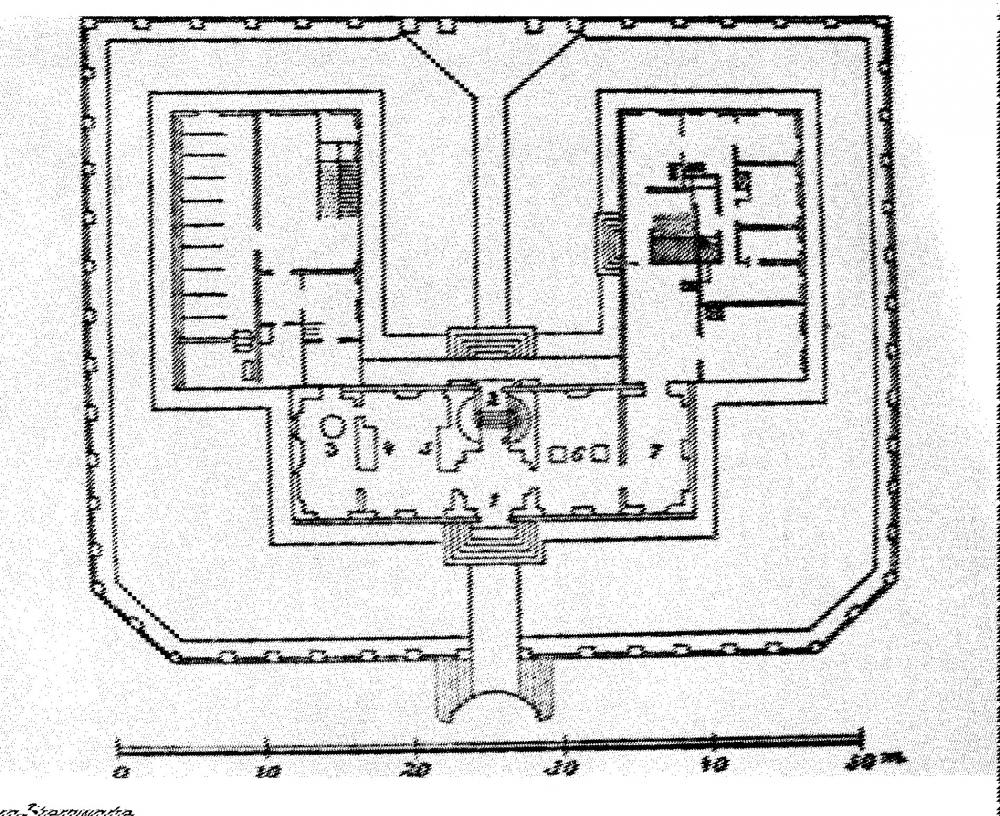

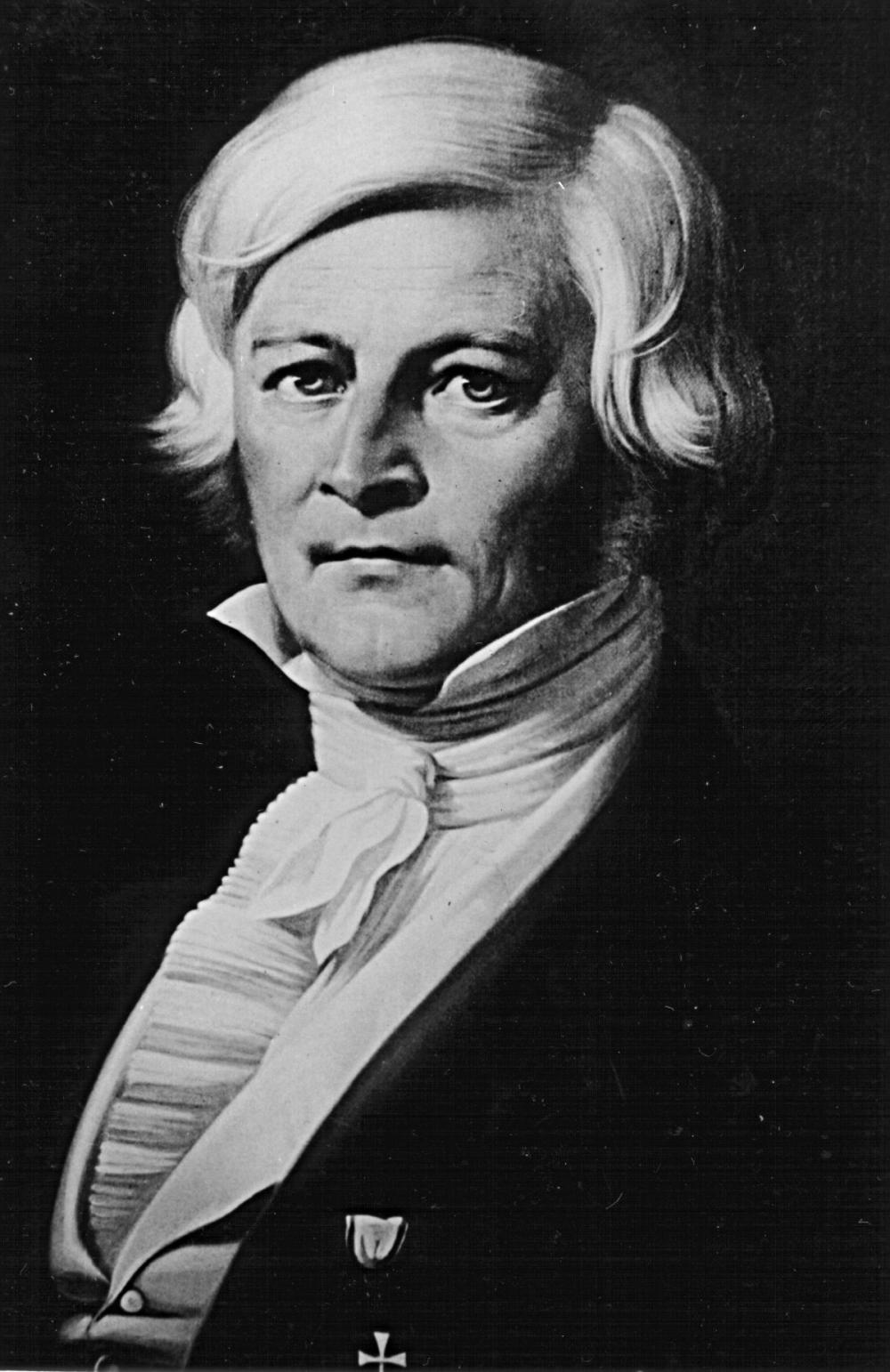

In 1787, Franz Xaver von Zach (1754-1832) planned a new observatory outside of Gotha on the top of hill Seeberg, financed by the Duke (building 36,000 Taler, instruments 20,000 Taler; for comparison: the director got several hundreds Taler/year). The focus of research was astrometry, timekeeping, geodetic and meteorological observations.

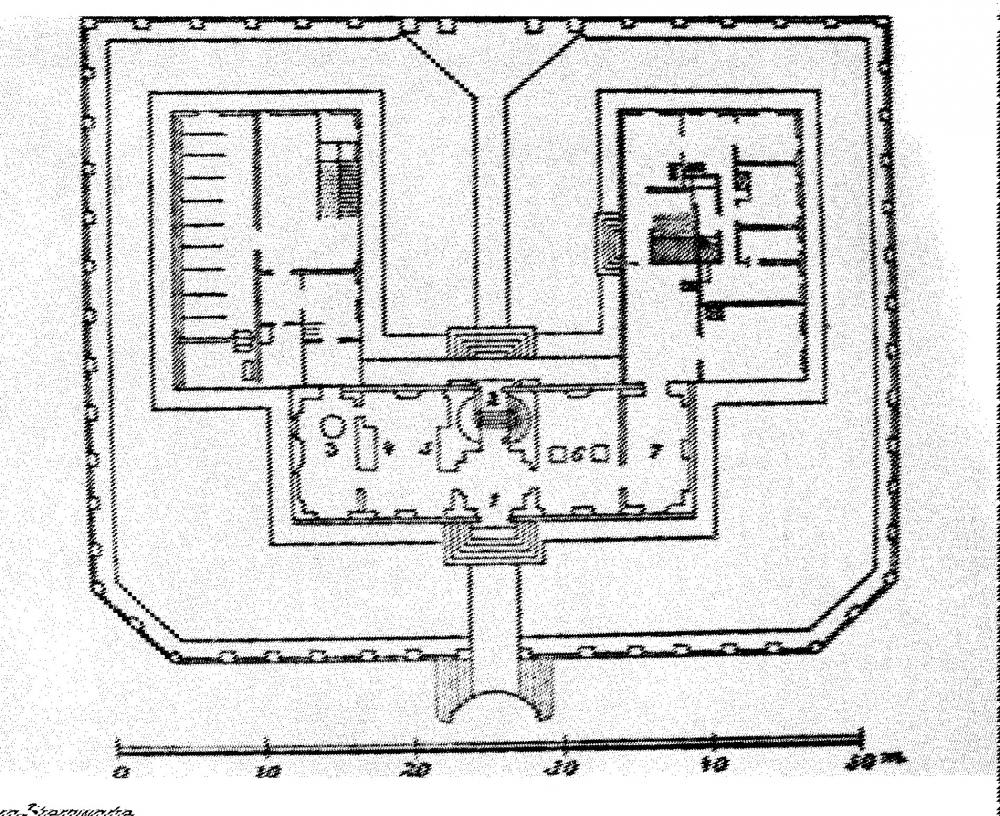

The observatory building, built by the Gotha architect and engineer Carl Christoph Besser (1724-1800), 1787-1789, was remarkable:

It was a massive building, erected on sand stone in east-west direction as meridian room, which provided space for the mounting of two wall quadrants, a passage instrument and the associated pendulum clocks. The observations were to be made through slits in the wall that allowed a clear view to the north or south horizon.

In the middle of the building, above the entrance hall, there was a small small - relatively high - circular tower with a revolving dome roof - one of the earliest examples of revolving domes - in which the Cary circle instrument was to be set up.

Zach had another innovative idea: he used the vaulted entrance room as a strong fundament (but not a pillar like in Dunsink Observatory Dublin (1785) and Armagh Observatory, Northern Ireland (1790)) for the mounting of the instrument, the Cary circle, and thus avoided the measurement errors that resulted from oscillating components of higher buildings.

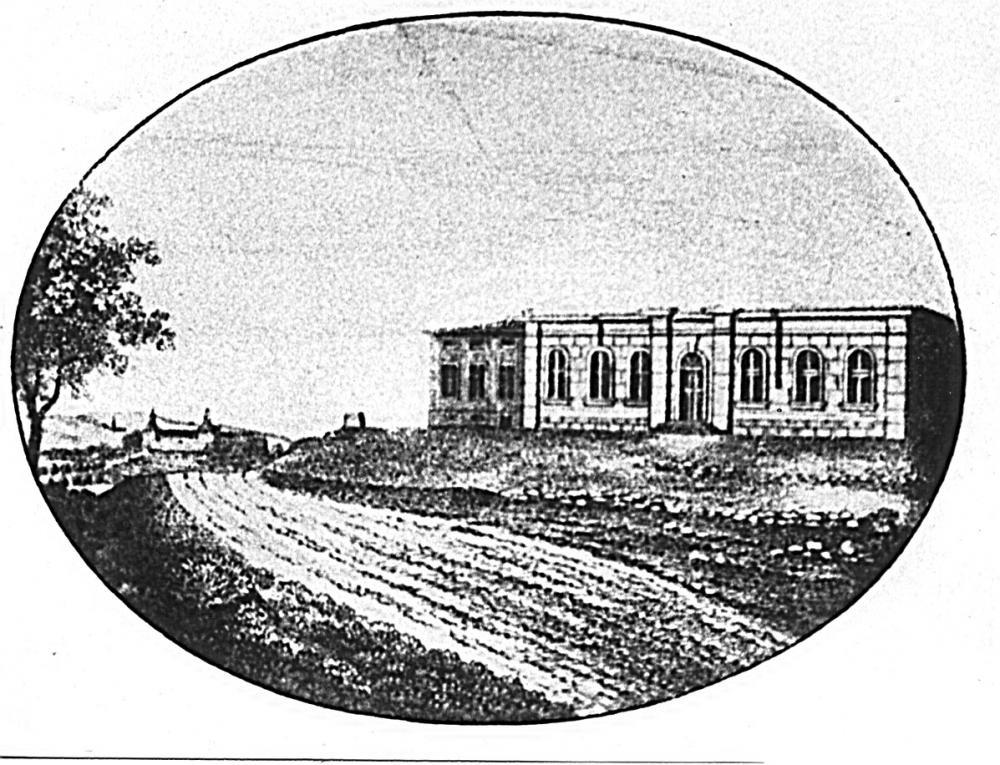

Later, it was discovered that the observing tower was too high and thus not stable enough for precision observations, and the tower was removed (Fig. 2b and 3a show the observatory without the tower including the dome).

Two side wings were intended as a home of the astronomer (eastern wing) and for the staff (5 servants), the guard (one "Ordonanz", one "Sergeant" and 3 soldiers) and stables for the 4 horses (western wing).

Fig. 1a. Franz Xaver von Zach (1754-1832) as Major (painting by Luise Seidel, Regionalmuseum Gotha, public domain)

Fig. 1b. Ernest II (1745-1804), Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, around 1800 (Wikipedia)

Zach's own description of the Seeberg observatory (1789)

"Das Gebäude selbst besteht aus einem länglichen Rechteck, das einen nördlichen (1) und eine südlichen (2) Haupteingang hat, dieser schneidet es in zwey Theile, davon jeder wieder in zwey Theile abgetheilt ist: in den einen kommt das Durchgangsinstrument von 8 Schuhen, mit der dazu gehörigen Pendeluhr (6), in die zweite Abtheilung wurden der südliche (4) und nördliche (5) Mauerquadrant placirt, in die dritte kommt der Zenith Sector (3).

Da ich geflissentlich nirgend, wo ich die Instrumente zu stehen habe, Feuerungen oder Kamine habe anbringen wollen, so dient die 4te Abtheilung (7) zur Stube, in der man in der Winterzeit sich erholen kann, ohne erst nötig zu haben ins Wohngebäude zurückzukehren. Aus dieser Eckstube, führt eine kleine Tür unmittelbar in mein Wohngebäude ...

Auf der Mitte der Sternwarte erhebt sich über dem stark gewölbten Eingang, ein kleiner Thurm mit einem runden beweglichen Kuppeldach, in denselben kommt ein beweglicher ganzer 8 schuhiger Zirkel ..."

("The building itself consists of an elongated rectangle that has a northern (1) and a southern (2) main entrance, which cuts it into two parts, each of which is divided into two parts: in one comes the transit instrument of 8 foot, with the associated pendulum clock (6), the southern (4) and northern (5) wall quadrants were placed in the second compartment, and the zenith sector (3) is in the third compartment.

Since I deliberately did not want to install any furnaces or fireplaces anywhere where I would have to keep the instruments, the 4th compartment (7) serves as a living room in which one can relax in the winter without having to return to the residential building first. From this corner room, a small door leads directly into my residential building ...

In the middle of the observatory, above the strongly arched / vaulted entrance, rises a small tower with a round, rotatable dome, in which there is a movable complete 8-foot circle instrument!),

(translated by the author GW).

Gotha's International Relationships

(Surveying, International Congres 1798, Astronomical Journals 1798)

Around 1800 the Gotha observatory was an international center for astronomy. Zach's visitors were not only astronomers but e.g. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) visited in 1801 the observatory; later it was used in 1829 in literature, in his "Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre". In 1798 the first international scientific congres took place, organized by Zach.

Franz Xaver von Zach travelled frequently to the south of France and to Italy with the Duke and Duchess of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg (since 1786). The Duchess Marie Charlotte Amalie also worked as "computer", she made scientific calculations. They visited Marseille Observatory, Genua and erected a small observatory in Hyères; a tower of the city wall was converted into an observatory in 1787.

Zach had made his first astronomical observations to determine geographical coordinates he realised that these old maps had an accuracy of at best some minutes of arc.

According to Hopf & Schwarz (1998), the king of Prussia, Friedrich Wilhelm III (1797-1840), asked Zach in October 1802 to start surveying in his territories. Zach considered a land survey of Thuringia similar to the French model. His ideas were promoted by the duke Ernest II. The documents in the Forschungs- and Landesbibliothek Gotha prove that the diplomatic preparations for the survey; Zach obtained passports and grants to pass and to survey some territories (Hessen-Kassel, Hannover, Coburg-Saalfeld, Braunschweig, Sachsen). The death of Ernest II in 1804, the consequences of the war (battle of Jena and Auerstedt in 1806) and Zach's resignation as director of the Seeberg observatory led to the end of the survey. But it was the starting point for the Prussian land surveying. As geodetic basis the measuring track was the distance from Seeberg observatory to Schwabhausen.

Why Zach is so important and we should have an interest in him today? There is a rational and an emotional answer as Brosche (2009) points out: First, he has rendered organisational services to his sciences which are equivalent to a great scientific achievement. Second, Zach was a very colourful character, travelled across many states in a time of radical changes and had connections with many colleagues and public figures.

Zach founded the first scientific astronomical journals and brought astronomers around the "world", mainly Europe at that time, in contact to each other, much easier than writing letters with astronomical results to everybody:

- Allgemeine Geographische Ephemeriden (Weimar 1798-1816), first ed. by Zach, since 1799 von Friedrich Justin Bertuch (1747--1822) and Adam Christian Gaspari (1752--1830);

- Monatliche Correspondenz zur Beförderung der Erd- und Himmels-Kunde (MC), Gotha 1800--1813 (28 Vol.), ed. by Zach, later by Bernhard August von Lindenau (1779--1854);

- Zeitschrift für Astronomie und verwandte Wissenschaften (ZfA), Tübingen 1816--1818 (6 Vol.), ed. by Bernhard von Lindenau and Johann Gottlieb Friedrich von Bohnenberger (1765--1831);

- Correspondance astronomique, géographique, hydrographique et statistique (CA), Genua 1818--1826 (15 Vol.), ed. by Zach.

Zach organized the first international scientific astronomical congres in 1798 together with the Paris astronomer Joseph Jérôme Lalande (1732--1807); 17 European astronomers participated: one quarter came from France, England, the Netherlands and Switzerland, the rest from the German states Prussia, Württemberg, Hannover and Saxony. New instruments, observing methods and proposals for new constellations were discussed, practical surveying on the Inselberg (916m high) were made. A critical point was the discussion about the instroduction of the new French metrical system; bacause of these revolutionary ideas some astronomers, especially from Austria, were not allowed to travel to this congres. This congres was the basis for the founduing of the first scientific astronomical society, the "Vereinigte Astronomischen Gesellschaft" (VAG) in 1800, which initiated the search for the missing planet between Mars and Jupiter; the result was the discovery of the first four asteroids.

History

Private Observatory in Castle Friedenstein in Gotha

Ernest II, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg (1745-1804) used the following instruments in his private observatory at castle Friedenstein in Gotha; it should be emphasized that all instruments were coming from London, England, was the center of instrument making in the 18th century:

A 18-inch quadrant made by Sisson, London; a small 2-ft transit instrument made by Ramsden, London [DM 67751]; three Hadley sextants; an achromat heliometer made by Dollond, London [DM 67750]; a 2-ft achromat refractor made by Ramsden, London [DM 67754]; a Gregory reflector made by Short, London [Gotha] and several clocks.

Fig. 2a. Footprint of Seeberg Observatory Gotha (im Catalogus Novus von 1792, Wikipedia)

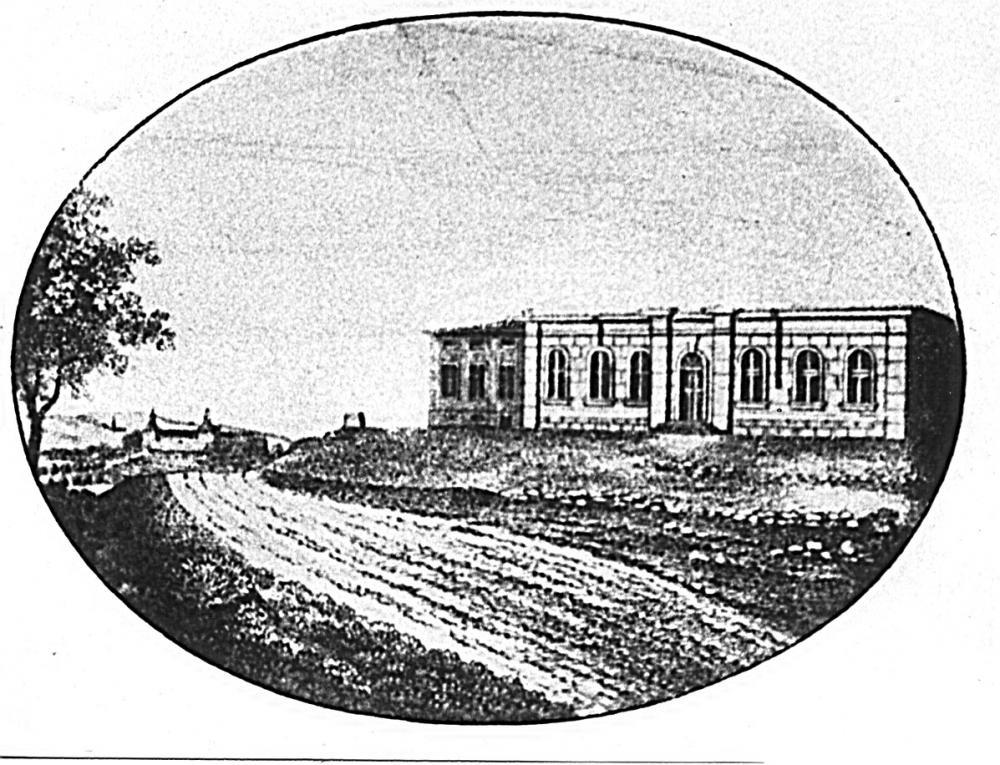

Fig. 2b. Gotha Observatory on the Seeberg hill (steel engraving, Wikipedia)

Seeberg Observatory Gotha and First Instruments

In 1787, Franz Xaver von Zach (1754-1832) planned a new observatory outside of Gotha on the top of hill Seeberg. The focus of research was astrometry, timekeeping, geodetic and meteorological observations.

Most of the instruments came from the leading instrument makers of that time (Wolfschmidt 1998, 2004):

(in brackets is indicated: place of the instrument today:

"DM" - Deutsches Museum Munich (with inventory number),

"Gotha" - Stiftung Schloß Friedenstein Gotha: Museum für Regionalgeschichte / Historisches Museum Gotha,

"Jena" - Jena Observatory):

A southern and a northern quadrant; a 8-ft transit instrument made by Ramsden, London, 1788 [DM 67743 a-c]; a 7-ft Herschel reflector [DM 67483]; a 2-ft vertical circle made by Cary, London, 1796; a 8-ft circle made by Ramsden, London, 1800; a 3-ft vertical circle made by Trougthon, London, 1800; a 3-ft equatorial refractor made by Dollond, London, 1796 [DM 67745 a, b]; a 3-ft equatorial refractor made by Schroeder, Gotha [DM 67746 a, b]; a 3-ft double refractor made by Dollond, London [DM 67747]; a 10-ft refractor mady by Dollond, London, 1796; a 2-ft comet seeker made by Baumann & Kinzelbach, Stuttgart [DM 67755], sideral clock made by Arnold and the master clock made by Mudge & Dutton.

By analyzing the instrumentation, we can see around 1800 a change in the kind of the instruments on one hand from quadrants and sextants to the vertical circle and on the other hand from the transit instrument to the meridian circle. Looking to the newer equipment we recognize a general trend: The English instrument makers did no longer play an important role after the beginning of the 19th century and in contrast the German instrument makers becoming prominent.

Seeberg Observatory Gotha and New Instruments of the 19th Century

In the 19th century, the Gotha observatory acquired new instruments (Wolfschmidt 1998, 2004):

A theodolit made by Reichenbach, Utzschneider & Liebherr, München [DM 67757 a, b]; a heliometer made by Fraunhofer, München, 1817 / in the 1850s: new mounting made by Ausfeld; a 3-ft meridian circle made by Ertel, ``Utzschneider & Fraunhofer'', München, 1826/30 [DM 67744 a, b].

For the new observatory in the town (after 1857): a 162-cm equatorial refractor (with 6-foot telescope and 2-foot circle) made by Repsold, Hamburg, optics: Steinheil, Munich, 1860, later replaced by Reinfelder & Hertel, Munich [Gotha]; a chronograph

introduced for galvanic registration of transits, a 90-cm transit instrument made by Carl Bamberg, Berlin, 1912 with Repsold's automatic recording device (unpersönliche Registriereinrichtung) [Jena].

Missed Opportunity: Introduction of Astrophysics

The only astrophysical equipment of the Gotha observatory was a Zöllner photometer made by Ausfeld, Gotha. Nothing for spectroscopy and photography could be found; this can not be only a problem of too less money.

According to Strumpf (2003) the administration of Gotha missed the opportunity to introduce astrophysics and to accept the application of the wealthy Hungarian Nobleman Nikolaus von Konkoly-Thege (1842-1916), a serious amateur astronomer and one of the pioneers of astrophysics; he applied even twice. Then Konkoly built his impressive private O'Gyalla Observatory (1874) (now in Hurbanovo, Nitra, Slovakia), moved as Konkoly Observatory to Budapest (1921).

The astronomers were still very much interested in astrometric topics, and for this purpose they got also new expensive clocks like Tiede and Riefler (siderial time clock, made by Christian Friedrich Tiede (1794-1877), Berlin, and clock made by Riefler, Munich).

Gotha was -- at the time of its founding -- the most modern astronomical institute with respect to its instruments.

Fig. 3a. Gotha Seeberg observatory - beginning of demolition (without dome), 1835 (public domain)

Fig. 3b. Ernst II monument on Seeberg (Wikipedia, Photo: Pimvantend)

End of Seeberg Observatory Gotha

The building was tumbledown after Zach's time. In 1810 the tower was dismantled, and in 1811 the two wings. In the west of the meridian room a new dwelling for the astronomer, the assistant and the castellan was erected.

In 1813, French troops damaged and distroyed the observatory building complertely and devastated the scientific papers.

The Seeberg Observatory directors

- Franz Xaver von Zach (1754-1832), 1787 to 1802/06

- Bernhard von Lindenau (1780-1854), 1804 to 1818/20

- Johann Franz Encke (1791-1859), 1822 to 1825

- Peter Andreas Hansen (1795-1874), 1825 to 1876, D

In addition there were assistants "Adjunkt", who later became famous astronomers like Johann Friedrich von Bohnenberger ((1765-1831, later Tübingen), Tobias Bürg (1766-1834, later Klagenfurt and 1792 Vienna), Johann Pasquich (1753-1829), Johann Karl Burckhardt (1773-1825, later Paris military school and observatory), Johann Kaspar Horner (1774-1834, Zürich).

For the rise of cartography in Gotha Bernhard August von Lindenau (1779-1834) and Adolf Stieler (1775-1826)was important.

Fig. 4a. Peter Andreas Hansen (1795 in Tondern (Schleswig) - 1874 in Gotha) (Wikipedia)

Fig. 4b. Hansen's Interim Observatory in his own house (PD)

New Gotha Observatory -- From Seeberg Hill to Town Center (1857/59)

In 1839, Peter Andreas Hansen (1795-1874) decided to build a dwelling house in the center of Gotha with a small observatory (interim observatory). In 1844 Hansen made plans to transfer also the observatory to the town (in 1856 the adminitration of Gotha allwed it). He decided to dismantle the old observatory on Seeberg hill, the meridian room in 1858.

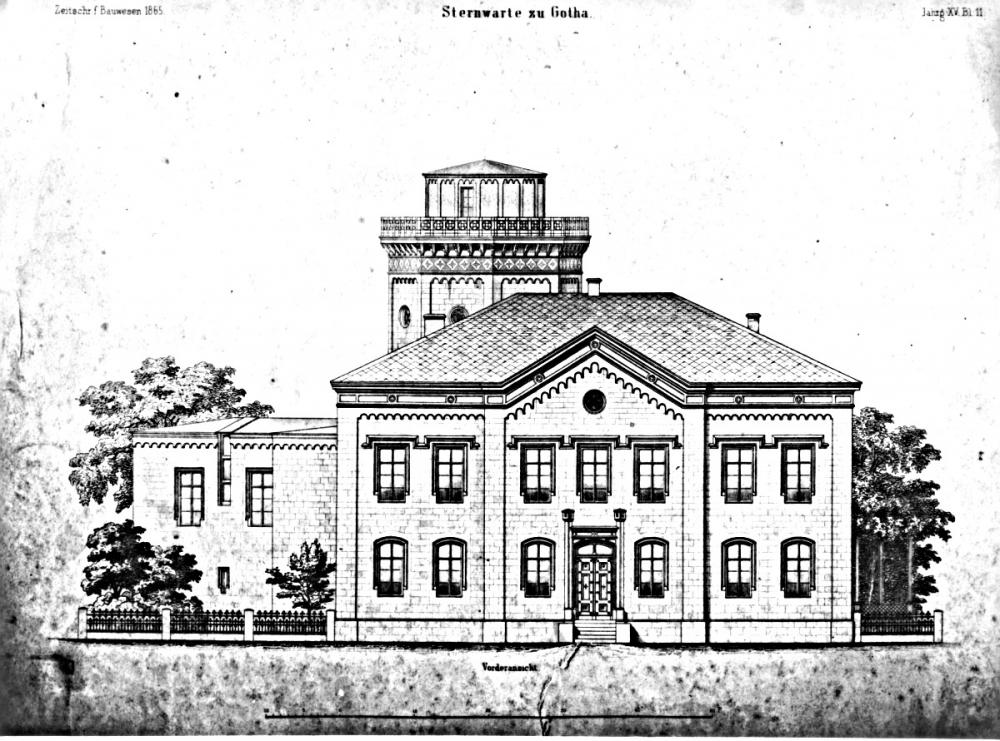

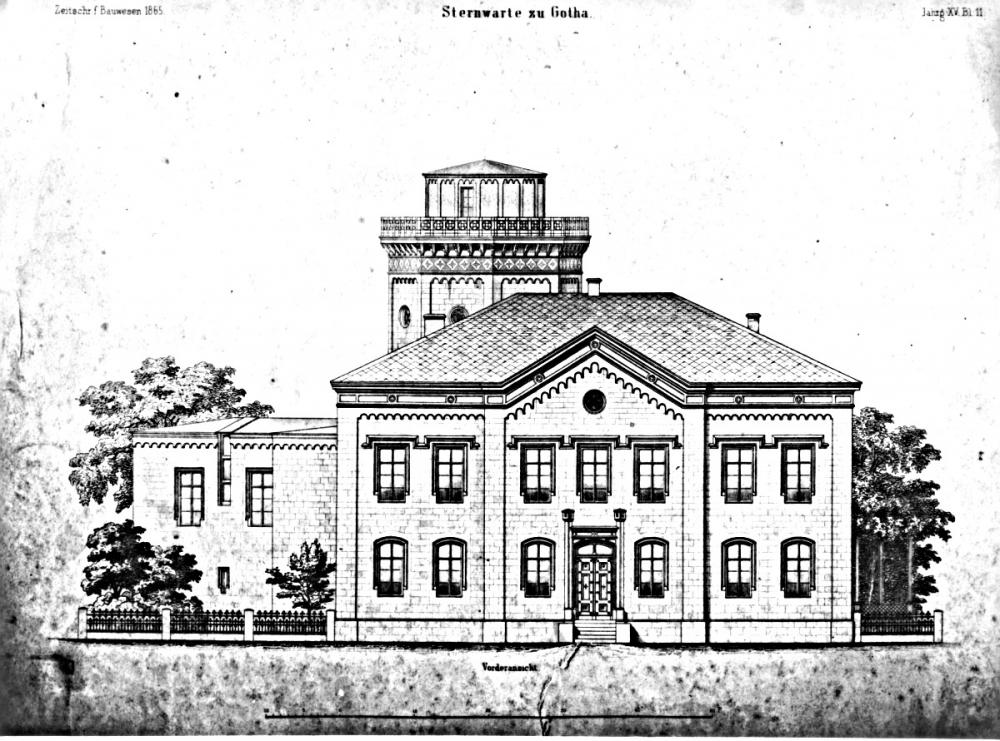

Fig. 5a. New Gotha observatory (1859) (Wikipedia)

Fig. 5b. New Gotha observatory, 1995 (Photo: Strumpf, PD)

A new observatory was erected by the Gotha architect Gustav Eberhard (1805-1880) in the town, Jägerstrasse 7, (1857 dwelling house, 1859 observatory), which was active until 1934.

Peter Andreas Hansen as the first director was interested in the theory and errors of instruments and especially in gravitational astronomy (perturbations of Jupiter and Saturn (published in Berliner Jahrbuch) - prize of the Berlin Academy in 1830, cometary disturbances - prize of the Paris Academy in 1850), "Fundamenta nova investigationis, &c., and the improved Tables of the Moon" (Hansen's Lunar Tables) 1838, 1857, which were rewarded with 1000 pounds by the British Government due to the importance for navigation (published in the Nautical Almanac in 1862), rewarded with a gold medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1842 and 1860.

The new Gotha Observatory directors

- Peter Andreas Hansen (1795-1874), 1860-1874, D

- Karl Nikolaus Adalbert Krueger (1832-1896), 1876-1880, D

- Hugo von Seeliger (1849-1924), 1881-1882, D

- Ernst Becker (1843-1912), 1883-1887, D

- Paul Harzer (1857-1932), 1887-1896, D

- Ernst Anding (1860-1945 ), 1906-1934, D

Vizedirector (VD), observator (O), assistant (A), administration (V):

- Johann Franz Encke (1791-1859), 1818, VD

- Leo Anton Carl de Ball (1853-1916), 1875-1878, A, V

- Ernst Jost (1861-1932 ), 1902-1904, O

- Carl Rohrbach (1861-1932), 1887-1906, V (Rohrbachturm, 1904, private observatory)

Closing of Gotha Observatory (1934)

In 1934 German astronomers had no success in preventing the closing of Gotha observatory. Most of the instruments went to the Deutsches Museum in Munich and some to the museum in Gotha.

State of preservation

Only the pillars for the meridian circle of the Seeberg observatory are visible as traces of the old Seeberg observatory.

In addition there is a monument (1904) for Ernest II, Duke of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg as founder of the Seeberg observatory, built in 1787-1791, and for Franz Xaver von Zach as first astronomer. The meridian room was demolished in 1858. The dwelling house served until a fire in 1901 as restaurant.

Then a new restaurant "Zur Sternwarte" (Old Observatory) was erected in 1904 ("Der Astronomie folgt die Gastronomie"), new restaurant in 1996.

Fig. 6. Restaurant "Zur Sternwarte" (Old Observatory), erected in 1904 (Wikipedia, Photo: Pimvantend)

New Observatory in Gotha

The building of the new Observatory in Gotha (Jägerstrasse), founded in 1857, is still existing.

In 2007 the renovated building got this label with a description:

"Dieses 1857 durch Baumeister Scherzer errichtete Gebäude diente als Wohn- und Arbeitsstätte von PETER ANDREAS HANSEN (1795-1874), BEDEUTENDER ASTRONOM UND GEODÄT DES 19. JAHRHUNDERTS. Seit 1825 trug er als Direktor der Gothaer Sternwarte durch astrometrische Beobachtungen, durch Berechnungen der Bahnen von Mond und Planeten mit ihren Störungen und durch die Konstruktion von Beobachtungsgeräten wesentlich zur Entwicklung der Astronomie in seiner Zeit bei. Als Geodät führte er ab 1838 die Landesvermessung des Herzogtums Gotha durch, entwickelte dabei neue Berechnungsmethoden wie die 'Hansensche Aufgabe' und war später leitend an der Europäischen Gradmessung beteiligt. Die 1859 hinter diesem Wohnhaus bezogene 'Neue Herzogliche Sternwarte' galt mit ihren Instrumenten als Musterbau eines astronomischen Observatoriums. -

Deutscher Verein für Vermessungswesen, Landesverein Thüringen, und Bund der öffentlich bestallten Vermessungsingenieure, Landesgruppe Thüringen, 2007."

The Seeberg Observatory and the new Gotha Observatory are no longer existing. But the legacy of famous astronomical instruments and the scientific output is still existing.

Comparison with related/similar sites

The model for inspiration was the Radcliffe Observatory in Oxford, England.

Seeberg Observatory with the U-shaped footprint served as a model for building other observatories like Göttingen Observatory.

Gotha had one of the earliest domes with the possibility to rotate. The earliest revolving domes, known in architectural history, can be found in King's Observatory, Kew (1768), a one dome observatory of the 18th century. Kew Observatory influenced the architecture of:

Seeberg Observatory, Gotha (*1788),

and the two Irish observatories, Dunsink Observatory Dublin (1785), and Armagh Observatory (1790) as well as later Göttingen Observatory (1803/16) with the dome.

It should be noted that Royal Madrid Observatory (1846) looks like it has a dome, but it is only an architectural feature, and cannot be opened for observing.

Threats or potential threats

The Seeberg Observatory is completely destroyed.

Present use

The observatory was closed in 1934.

Now the building, Jägerstraße 7, 99867 Gotha, is in private use (Planungsgruppe 91 Architekt).

Astronomical relevance today

The Seeberg Observatory and the new Gotha Observatory are no longer existing as an astronomical institution.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles)

- Anding, Ernst: Die Sternwarte. In: Schmidt, K. (Hrsg.): Gotha. Das Buch einer deutschen Stadt. Heft 7: Die wissenschaftlichen Sammlungen und Anstalten der Stadt Gotha. Gotha: Verlag Engelhard-Reyher 1933, p. 121-136.

- Anding, Ernst: Zur Gründung der Sternwarte Gotha. Erwiderung an Herrn Zinner auf VJS 77, S. 281. In: Vierteljahrsschrift der Astronomischen Gesellschaft 79 (1944), p. 92-98.

- Armitage, A.: "Baron von Zach and his astronomical correspondence". Popular Astronomy. 57 (1949), p. 326-332.

- Beck, Daniel A: Life on the Moon? A Short History of the Hansen Hypothesis. In: Annals of Science 41 (1984), p. 463-470.

- Brosche, Peter: Gotha 1798. Vorder- und Hintergründe des ersten Astronomenkongresses. In: Photorin, Mitteilungen der Lichtenberggesellschaft, Heft 5 (Juni 1982), p. 38-59.

- Brosche, Peter: Gotha und der Seeberg. Zum 200. Gründungstag eines astronomischen, geodätischen und kartographischen Zentrums der Goethezeit. In: Sterne und Weltraum 27 (1988), p. 423-427.

- Brosche, Peter: Franz Xaver von Zach und die Gründung der Seeberg-Sternwarte bei Gotha 1788. In: Jahrbuch der Coburger Landesstiftung 33 (1988), p. 173-204.

- Brosche, Peter; Dick, Wolfgang W.R.; Schwarz, O.; Wielen, R. (Hg.): The Message of the Angles -- Astrometry from 1798 to 1998. Proceedings of the International Spring Meeting of the Astronomische Gesellschaft, Gotha, May 11-15, 1998. Acta Historica Astronomiae, Vol. 3. Thun/Frankfurt am Main: Harri Deutsch 1998, p. 89-90.

- Brosche, Peter: Der Astronom der Herzogin - Leben und Werk von Franz Xaver von Zach 1754-1832 [The astronomer of the duchess - Life and work of Franz Xaver von Zach 1754-1832]. Frankfurt am Main: Verlag Harri Deutsch (2., überarb. u. erw. Aufl.) 2009.

- Caplan, James & Marie-Louise Prévot: Zach in Marseille. In: Brosche et al. 1998, p. 76-77.

- Dick, Julius: Auf den Spuren Peter Andreas Hansens. In: Die Sterne 42 (1966), p. 145-154.

- Dick, Julius: Nochmals: Auf den Spuren Peter Andreas Hansens. Richtigstellungen und Ergänzungen. In: Die Sterne 44 (1968), p. 66-70.

- Dick, Wolfgang R. & Jürgen Hamel (ed.): Astronomie von Olbers bis Schwarzschild. Nationale Entwicklungen und internationale Beziehungen im 19. Jahrhundert. [Astronomy from Olbers to Schwarzschild. National developments and international relations in the 19th century]. Frankfurt am Main: Verlag Harri Deutsch (Acta Historica Astronomiae, Vol. 14) 2002.

- Finck, Wolf-Dieter: Christian Friedrich Tiede - Königl. Astronomischer und Hof-Uhrmacher in Berlin. In: Alte Uhren. München: Callwey-Verlag 1982, Heft 1, p. 9-11.

- Hansen, Peter Andreas: Die Einrichtung der neuen herzoglichen Sternwarte in Gotha. In: Berichte der math.-phys. Classe der Königl. Sächsischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften 1859.

- Hansen Taylor, Marie & Lilian Bayard Taylor Kiliani: On Two Continents: Memories of Half a Century. New York: Doubleday & Page 1905 (307 Seiten).

- Hopf, Cornelia & Oliver Schwarz: Geodetic documents in the Gotha library. In: Acta Historica Astronomiae Vol. 3 (1998).

- Harzer, Paul: Die Astronomie in Gotha. Generalversammlung in Gotha 1.-3. Sept. 1894. In: Mitteilungen der Vereinigung von Freunden der Astronomie und kosmischen Physik [VAP] 4 (1894), p. 125-135.

- Inventarverzeichnis der Herzoglichen Sternwarte. In: Forschungsbibliothek Gotha, Chart A 2139.

- Jost, Ernst: Die Sternwarte auf dem Seeberg. In: Ehwald, Rudolf (Hg.): Aus den coburg-gothaischen Landen. Heimatblätter, Heft 3. Gotha: Perthes-Verlag 1905, p. 27-40.

- Kienle, Hans: Astronomie. In: Hartmann, Max (Hrsg.); 25 Jahre Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften, 2. Band: Die Natur wissenschaften. Berlin 1936, p. 36-45.

- Knopf, Otto: Ein Mahnwort zur Sicherung des fortdauernden Bestandes der Gothaer Sternwarte. Jena 1920.

- Lloyd, H. Allen: The Collectors Dictionary of Clocks, S. 22. Gesch 10178a

- Scherzer, R.: Sternwarte zu Gotha. In: Zeitschrift für Bauwesen 15 (1865), S. 11-16, Zeichnungen im Atlas Blatt 11 bis 13.

- Schmadel, Lutz D.: Dictionary of minor planet names. Springer (5th ed.) 2003, p. 109.

- Schwarz, Oliver & Manfred Strumpf: Peter Andreas Hansen und die astronomische Gemeinschaft - eine erste Auswertung des Hansen-Nachlasses. In: Acta Historica Astronomiae Vol. 1 (1998).

- Schwarz, Oliver & Manfred Strumpf: Peter Andreas Hansen and the astronomical community - a first investigation of the Hansen papers. (German Title: Peter Andreas Hansen und die astronomische Gemeinschaft - eine erste Auswertung des Hansen-Nachlasses.) In: Acta Historica Astronomiae Vol. 1 (1998), p. 141-154.

- Siegert, Jutta: Die deutsche Landesvermessung des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts, unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des sächsisch-thüringischen Raumes und der daraus entstandenen Kartenwerke. In: Museum für Regionalgeschichte und Volkskunde Gotha (Hg.): Museumsheft ’91 - Beiträge zur Regionalgeschichte. Gotha 1991.

- Strumpf, Manfred & Marold, Thomas: Astronomie in Gotha. II. Die Sternwarte in der Jägerstraße. In: Die Sterne 56 (1980), p. 227-236.

- Strumpf, Manfred & Thomas Marold: Zur Geschichte der Sternwarten Gothas. In: Gothaer Museumsheft 1985, p. 33-48,

- Strumpf, Manfred & Marold, Thomas: Sachzeugen der "astronomischen Epoche" Gothas - Zum 200. Jahrestag der Errichtung der Sternwarte auf dem Seeberg. In: Gothaer Museumsheft - Abhandlungen und Berichte zur Regional geschichte (1988), p. 17-25, 13 Abbildungen: Tafel 7,1 bis 12,2.

- Strumpf, Manfred: Gothas astronomische Epoche. Horb am Neckar: Geiger-Verlag 1998.

- Strumpf, Manfred: Zach’s letters and messages to the Dukes of Gotha 1786-1805. (German Title: Briefe und Mitteilungen Zachs an die Herzöge von Gotha 1786-1805). .... 2000.

- Strumpf, Manfred: Evaluation in the 19th century - how astronomers were chosen for Gotha observatory. (German Title: Evaluation im 19. Jahrhundert - wie Astronomen für die Sternwarte Gotha ausgesucht wurden). In: Duerbeck, H.W.; Dick, Wolfgang R. & Jürgen Hamel (ed.): Beiträge zur Astronomiegeschichte, Band 5 (Acta Historica Astronomiae Vol. 18) 2003, p. 166-181.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: ’’Gotha - the Instruments of the Observatory.’’ In: Brosche, Peter; Dick, Wolfgang R.; Schwarz, Oliver; Wielen, Roland (ed.): The Message of the Angles - Astrometry from 1798 to 1998. Proceedings of the International Spring Meeting of the Astronomische Gesellschaft, Gotha, May 11-15, 1998. Thun, Frankfurt am Main: Harri Deutsch (Acta Historica Astronomiae, Vol. 3) 1998, p. 89-90.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Gotha - an International Center of Astronomy at the Time of Goethe. In: Klare, G. (Hg.): Astronomische Gesellschaft Abstract Series No. 7, 1992. Hamburg 1992, p. 202.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Beobachtungsinstrumente der Sternwarte Gotha zur Zeit Hansens. In: Ostwald, Jürgen (Hg.): Von Tondern nach Gotha. Der Astronom Peter Andreas Hansen 1795-1874. Aabenrade/Dänemark (Nordschleswiger Hefte, Heft 1) 1995, p. 35-45.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Gotha - the instruments of the observatory. In: Acta Historica Astronomiae (ACHA), vol. 3 (1998), p. 89-90.url{1998AcHA....3...89W}.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Zach’s instruments and their characteristics. In: In: The European Scientist. Symposium on the era and work od Franz Xaver von Zach (1754-1832). Proceedings of the Symposium held in Budapest, on September 15-17, 2004. Edited by Lajos G. Balázs, Peter Brosche, Hilmar W. Duerbeck and Endre Zsoldos. Frankfurt am Main: Harri Deutsch (Acta Historica Astronomiae, Vol. 24) 2004, p. 83-96.

- Zimmermann, B.: Peter Andreas Hansen (1795 bis 1874). In: Vermessungstechnik 22 (1974), p. 103-105.

- Zinner, Ernst: Anding, E.: Einrichtung und Geschichte der Sternwarte Gotha. In: Vierteljahrsschrift der Astronomischen Gesellschaft 77 (1942), p. 281-283.

Links to external sites

Stiftung Schloß Friedenstein Gotha

Links to external on-line pictures

No multimedia content published

Currently there is no multimedia content published for this case study