Category of Astronomical Heritage: tangible immovable

Seven-stone Antas, Portugal/Spain (multiple locations): General Description

Identification of the property

Country/State Party

Portugal / Spain

State/Province/Region

- Alandroal, Arraiolos, Estremoz, Évora, Mora, Reguengos de Monsaraz, and Redondo municipalities, Évora district, central Alentejo region, Portugal

- Castelo de Vide, Crato, Elvas, Nisa, and Ponte de Sor municipalities, Portalegre district, central Alentejo region, Portugal

- Ourique municipality, Beja district, Baixo Alentejo region, Portugal

- Santiago do Cacém municipality, Setúbal district, Baixo Alentejo region, Portugal

- Agualva, Loures, and Sintra municipalities, Lisboa district, Grande Lisboa region, Portugal

- Barcarrota, Jerez de los Caballeros and Mérida municipalities, Badajoz province, Extremadura region, Spain

- Cedillo and Valencia de Alcántara municipalities, Cáceres province, Extremadura region, Spain

- Aroche and Rosal de la Frontera municipalities, Huelva province, Andalusia region, Spain

Name

186 individual names as listed in Table 1 below.

Geographical co-ordinates and/or UTM

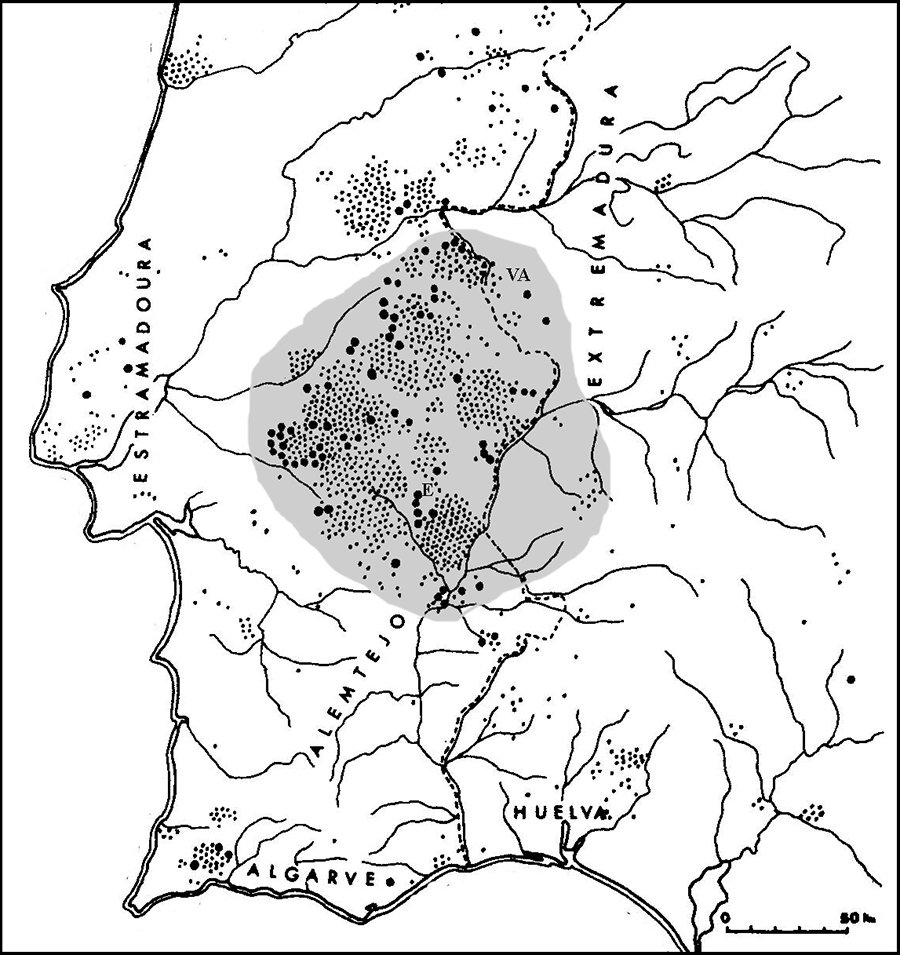

The seven-stone antas identified in Table 1 occupy 186 separate locations concentrated in the central Alentejo region, Portugal, and the provinces of Badajoz and Cáceres, Extremadura region, Spain. Their latitudes vary from 37.8° to 39.6° N, their longitudes vary from 8.2° to 7.0° W, and their elevations range from c. 200m to 580m above mean sea level.

The Portuguese sites are mostly located within the limits of the Évora and Portalegre districts, an area to the south and west of Elvas, close to the Spanish frontier, and just below the latitude of Lisbon.

Note concerning the location of site markers on the portal finder mapsThe precise locations of anta sites, where known, are listed in Table 1, and shown correspondingly on the maps. However, in many cases the latitude is only quoted in publications to a precision of 0.1° and the longitude is unavailable. In these cases, the marker on the finder map is placed at the exact decimal latitude and at a longitude which is an exact multiple of 0.01° and which places the marker in the correct municipality. Within some municipalities, several such sites appear on the map in a straight east-west line. Users are encouraged to contact the portal team if they know of more accurate positions for any of the anta sites concerned.

Maps and plans,

showing boundaries of property and buffer zone

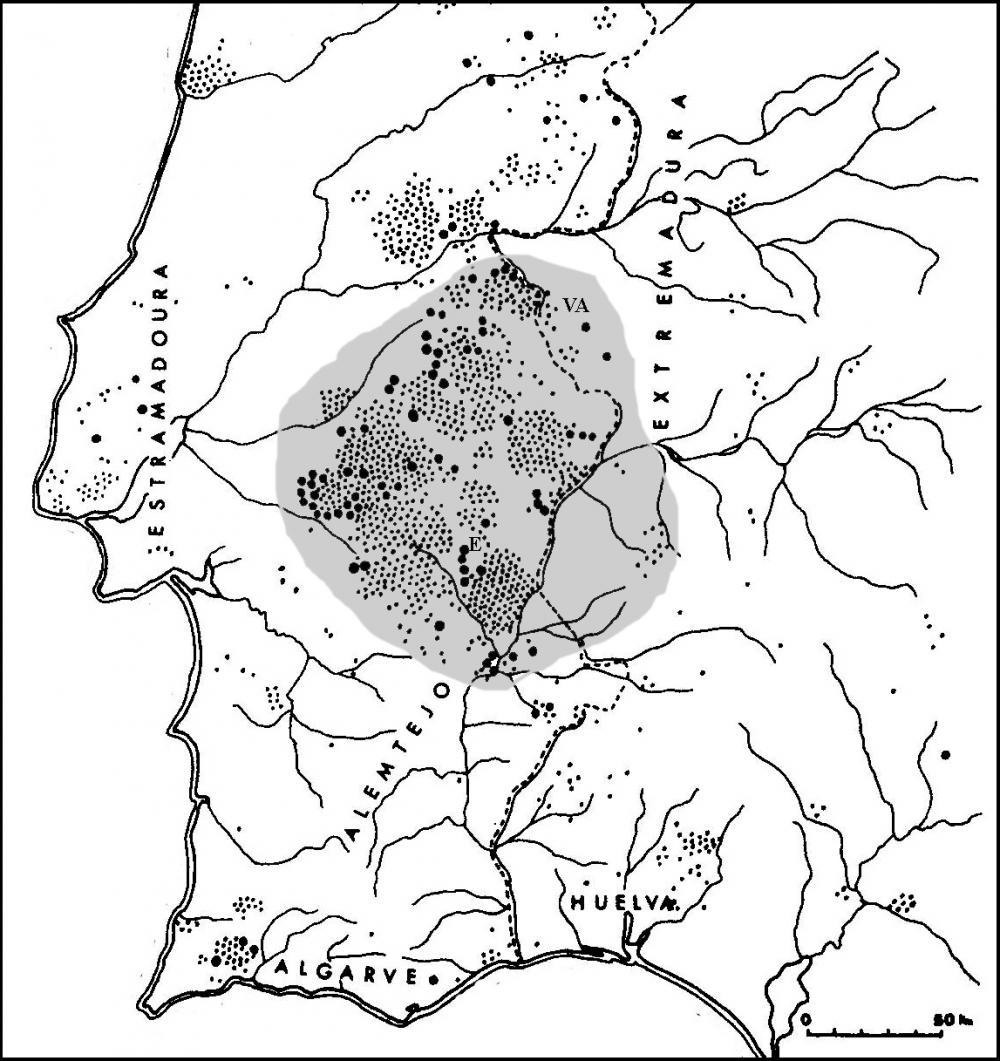

Fig. 1. The neighbouring regions of Alentejo (Portugal) and Extremadura (Spain) where seven stone antas can be found. The vast majority are in Portugal (notice the huge concentration around Évora, E in the map), hence the common name of Antas Alentejanas by which they are also known. The Spanish town of Valencia de Alcántara (VA) is also shown on the map. Adapted from Belmonte and Hoskin (2002), fig. 2.

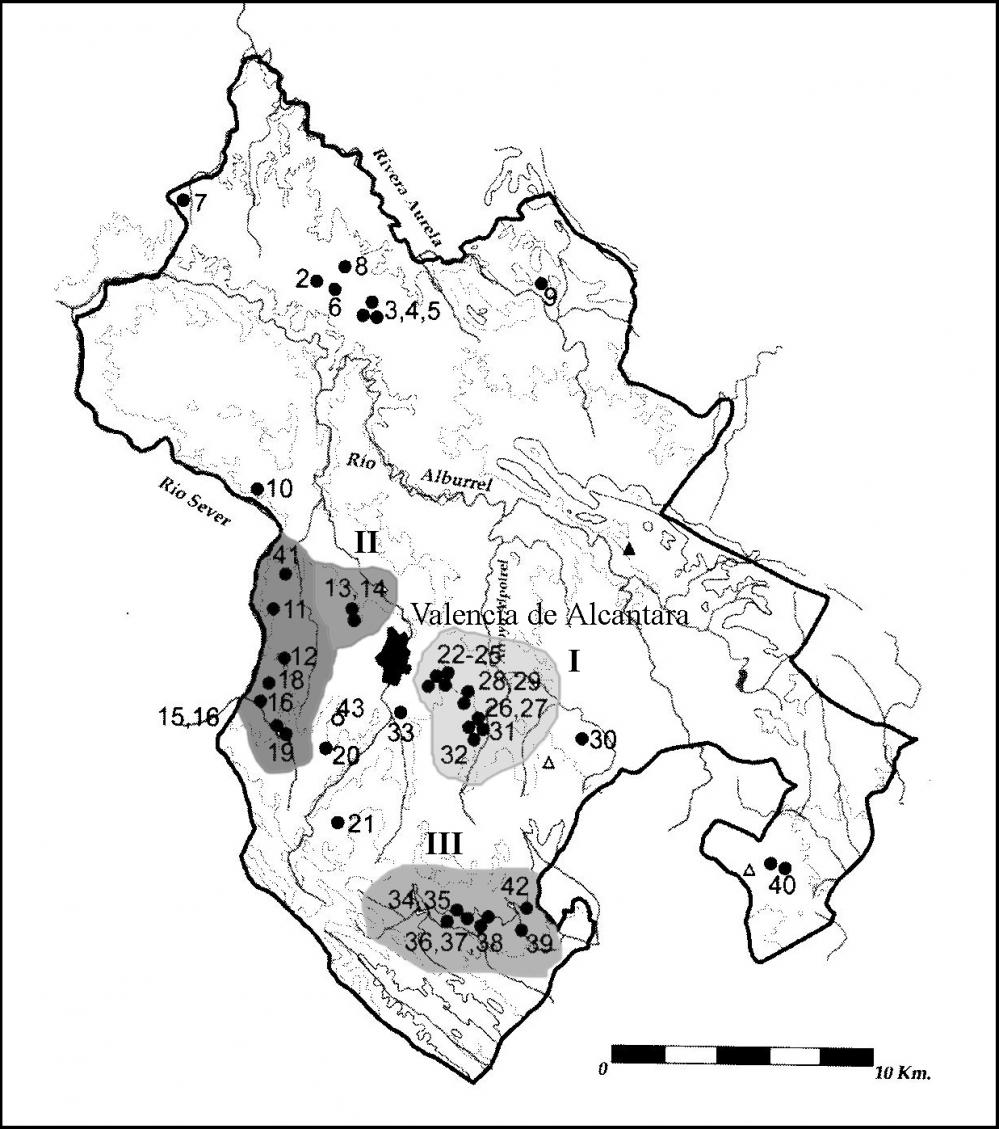

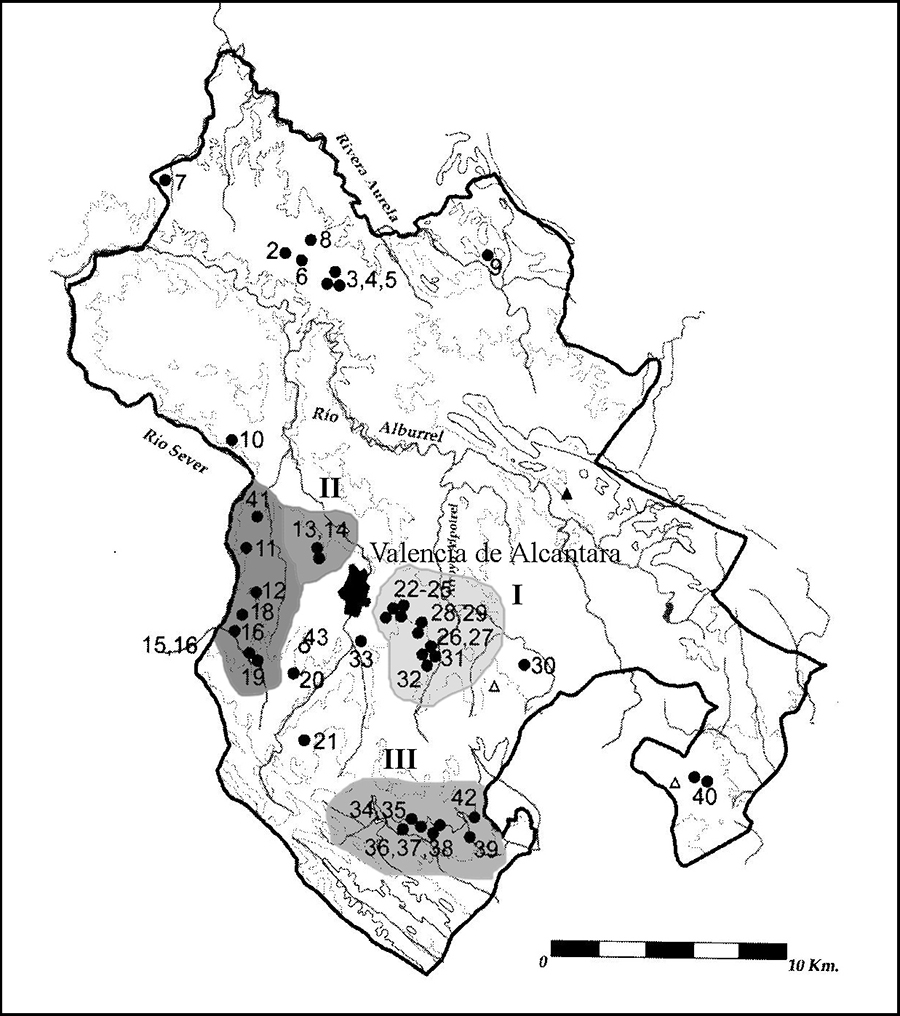

Fig. 2. Map of the Valencia de Alcántara municipality showing the areas discussed below where well-preserved groups of seven-stone antas, conforming to the ‘standard’ design and orientation pattern, are located. These are (I) Collados de Barbón, (II) Río Sever banks and (III) the granite outcrop of Santa María de la Cabeza (in light, dark and middle tone grey respectively). Dolmens 2 to 9 were built of schist and poorly preserved. The river Sever forms the frontier between Spain and Portugal. A handful of antas can be found on its west (Portuguese) bank. For details see Table 2. Adapted from Bueno Ramírez and Vázquez Cuesta (2008).

Area of property and buffer zone

Seven-stone antas are distributed over an area approximately 100km east to west, from about 50km from the coast near Lisbon to the Spanish border provinces, and a little over 200km from south to north, from Ourique to the River Tejo (see Fig. 1).

Description

Description of the property

General description

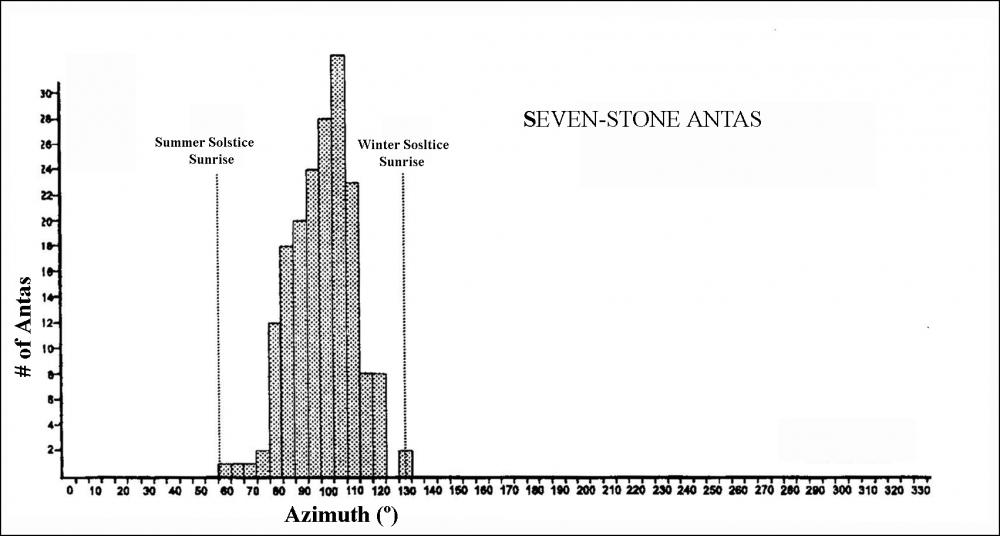

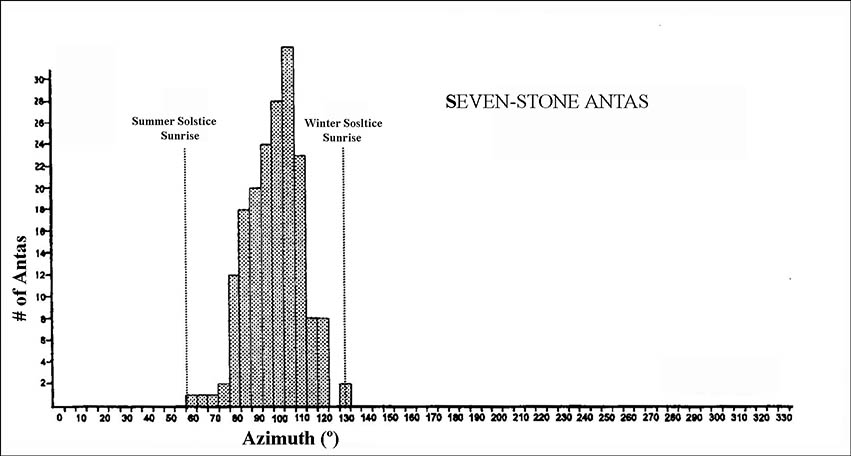

The seven-stone antas are a distinctive form of megalithic tomb. The 177 examples whose principal orientation has been reliably determined all, without exception, face within the arc of sunrise (the part of the horizon where the sun rises at some time during the year) or moonrise (see Fig. 7). The extraordinary consistency in an orientation pattern that extends over hundreds of kilometres provides an exceptionally clear indication of its astronomical origin.

They were built in a wide area extending over the present day regions of Alentejo, in Portugal, where most of the antas are located, and Extremadura, in Spain (see Fig. 1). The main concentrations of sites within the group with the best preserved and some of the most impressive monuments are around the towns of Évora (Portugal) and Valencia de Alcántara (Spain).

The name anta is the Portuguese term for dolmen and will be loosely used as a synonym throughout this case study, although the Spanish counterparts are normally denoted as dolmens in the corresponding archaeological or tourist literature.

The seven-stone antas can easily be described as standard corridor dolmens but their most impressive features are that

- they were constructed using a surprisingly consistent architectural design (see Figs 3, 4, 5) over an extended period of time (hence their common name); and

- they manifest a pattern of orientations that place them among the oldest monuments on Earth with indisputable astronomical orientations.

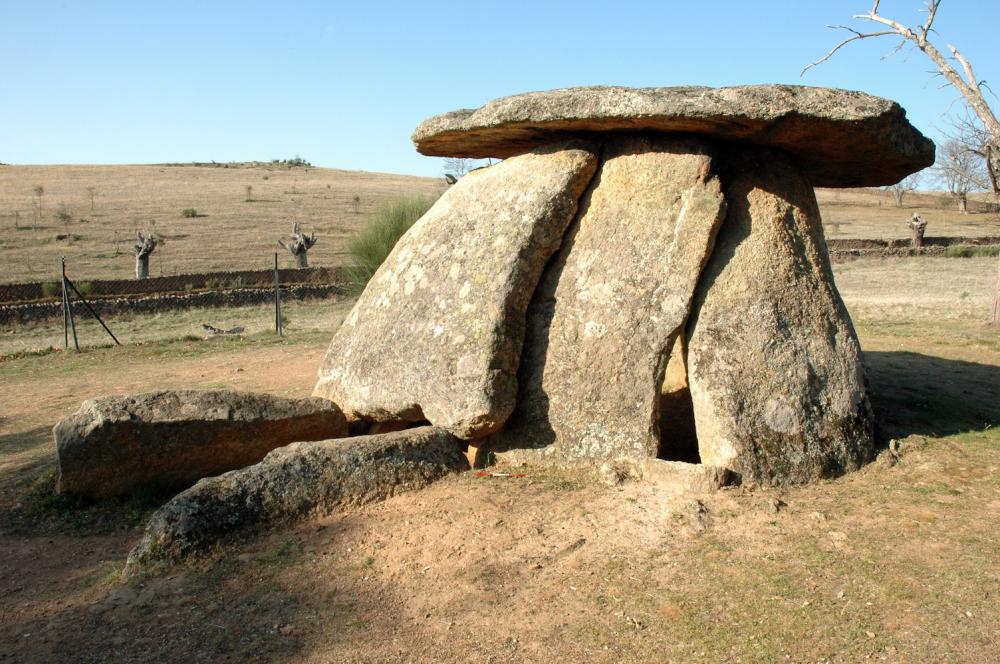

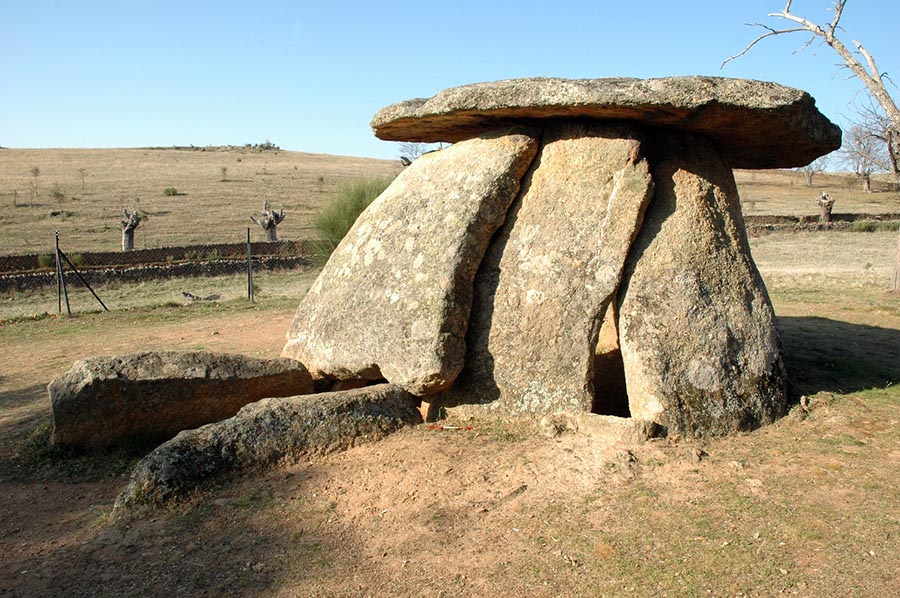

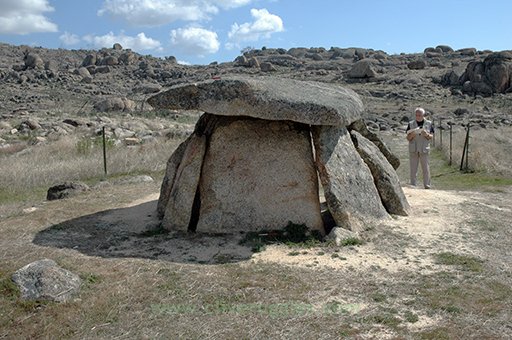

Fig. 3. Tapias 1 (no. 143 in Table 1), a good example of a seven-stone anta, well-preserved, in the vicinity of Valencia de Alcántara, Spain. Photograph courtesy of Margarita Sanz de Lara

Form and construction

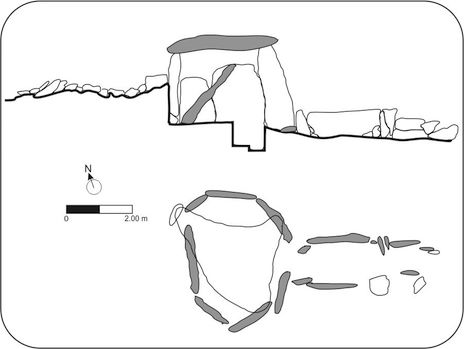

Fig. 4. Huerta de las Monjas (no. 3 in Table 1), a typical long-corridor seven-stone anta on the eastern bank of the river Sever. Plan (top) adapted from Bueno Ramírez (1988). Photograph (bottom) courtesy of Margarita Sanz de Lara

The seven-stone antas (dolmens) were mostly constructed using tall blocks of granite, typically 3m or more in height. In some areas to the north the builders used smaller blocks of schist but as a result these examples are mostly in a poor state of preservation. Seven-stone antas are distinguished from other megalithic tombs found in the same and neighbouring regions by two factors. The first is the presence of a passage—shorter or longer depending on the date of construction: the seven-stone antas are thought to have been constructed from c. 4000 BC onwards, with longer corridors appearing around 3200 BC.

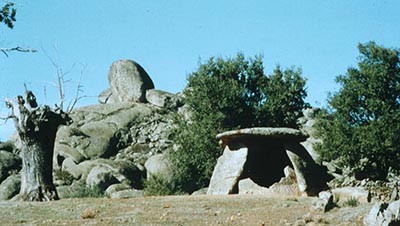

The second factor is their distinctive method of construction. This involved erecting a backstone and then leaning three uprights in succession on each side so as to form a chamber typically some 4m to 5m in diameter with a clearly defined entrance to which a passage of smaller orthostats was attached (see Fig. 4). In very few cases, an eighth orthostat, acting as a sort of front stone, has been preserved; it is unknown if this component was more frequent than the present state of preservation of many monuments may indicate (see Fig. 5). In any case, the dominant feature is the seven-orthostat chamber, as the name suggests.

Among the Alentejo antas are a few exceptional monuments, in particular the Anta Grande do Zambujeiro, a huge dolmen with a chamber 6m high and orthostats measuring nearly 8m. Another is the complex monument at Olival da Pega 2 (Reguengos de Monsaraz), excavated by Victor S. Goncalves in the 1990s, where a corridor 16m long was found. The excavations here demonstrated various reutilizations and structures added at different times.

Fig. 5. Anta de la Marquesa, also known as Mellizo (no. 101 in Table 1), a good example of a short-corridor seven-stone anta with the addition of an eighth orthostat blocking the corridor. Photograph © Clive Ruggles

Landscape

Fig. 6. The typical landscapes where seven-stone antas can be found: the plains of central Alentejo (top) and the granite outcrops of the north-east (bottom), including the Spanish sector close to Valencia de Alcántara. Photographs © Luís Tirapicos (top) and Juan Belmonte (bottom)

Most of the region in which the seven-stone antas are found comprises low hills with scattered granite outcrops, the latter being where the quarries are usually located. However, to the north-east, in the Spanish sector and on the Portuguese side close to the border, the terrain is scarped by small mountain ranges and large granite outcrops (see Fig. 6).

Orientation

The orientation of each of these monuments can be determined (according to the state of preservation) either from the alignment of the stones forming the corridor or from the direction perpendicular to the backstone, or both. All of them point towards the eastern half of the horizon, within about 25° of due east. Such a strong consistency in orientation could not have been achieved using topographic referents such as conspicuous distant mountain peaks: the Alentejo region, in particular, is a very flat area. This implies that the target used to determine the orientations was a celestial object.

The range of the 177 measured orientations corresponds almost exactly to the range of possible rising positions of the sun. In other words, every tomb in the group without exception is oriented within the arc of sunrise, corresponding to about one sixth of the available horizon (Figs. 7, 8). In almost all cases the orientations fall between azimuths of 61° (29° north of east) and 122° (32° south of east); there are two exceptions, which are oriented more towards the south (azimuth 128°-129°), but these are within a deep valley with a higher eastern horizon, and so still face sunrise. This remarkable statistic provides the strongest possible indication of an association between these tombs and the sun. If the tombs were oriented to face sunrise on the day when construction began, then the distribution of azimuths would suggest that this took place predominantly in the spring or autumn, but the fact that orientations span the entire solar rising range implies that in some cases construction was commenced in the middle of summer or winter. The ‘exactness of fit’ between the range of tomb orientations and the arc of sunrise suggests that the tombs were aligned with a precision of about 1-2 degrees (2-4 solar diameters). This is indeed the easiest explanation applying Ockham’s Razor.

It remains possible to argue that the moon rather than the sun was used to determined the orientations, since any possible solar orientation can also be interpreted as a lunar one (the lunar rising arc on the horizon being somewhat wider than the solar one). In 2004, using the data collected by Hoskin and collaborators, Cândido Marciano da Silva proposed a new interpretation explaining the orientations of the antas. According to da Silva’s statistical analysis the entrance of seven-stone antas of Alentejo, and neighbouring regions, may have been oriented to the full moon rise near the vernal equinox - when the positions of the rising sun and moon ’cross-over‘ on the horizon. This idea can be further supported by historical and ethnographical sources. It must be emphasized, however, that the solar explanation fits the observed orientation data closely and simply, and the fact that scientific debate continues about the precise nature of the astronomical target does not in any way cast doubt upon the assuredly astronomical character of the alignments of the seven-stone antas.

Fig. 7. Orientation histogram of 177 seven-stone antas as obtained by Hoskin and collaborators after several years of fieldwork in the region. How every single monument fits within the sector of sunrise (or moonrise) is clearly illustrated. The strength of this evidence makes the seven-stone antas the oldest group of monuments for which there is incontrovertible proof of their connection to astronomy. Adapted from Hoskin (2001), p. 98

Fig. 8. Aldeia da Mata, Crato, northern Alentejo (no. 49 in Table 1) facing the rising sun. Photograph © Luís Tirapicos

Inventory

Table 1 lists the 177 seven-stone antas listed by Hoskin (2001, Table 6.2), for 173 of which measured orientations were obtained by Hoskin (2001), together with an additional 9 sites in the Valencia de Alcántara area identified more recently. The sites are ordered by their direction of orientation (azimuth). Where necessary, the name has been corrected from that provided by Hoskin. The latitude and longitude is given correct to the nearest 1’’ (approx. 25m) where available (sources C, D, R as below); otherwise the latitude is given to the nearest 0.1° (approx. 150m) as provided by Hoskin (H). Azimuth, altitude and orientation data are also taken from Hoskin’s table; T under azimuth indicates that, although the exact orientation was unmeasurable, this dolmen faced a ’typical direction‘ (i.e., in the solar rising range) according to Hoskin (2001: 232).

Column headings

No. = Reference number in this case study

N4 = Number shown in Fig 2.

Group = Group as shown in Fig 2.

Dist/Prov = District [Portugal] or Province [Spain]

Lat = Latitude (N) in degrees to the nearest 0.1°, supplied where more accurate information unavailable

Lat N = Latitude (N) in deg/min/sec, to the nearest second

Long W = Longitude (W) in deg/min/sec, to the nearest second

S = Source for co-ordinate information (see key below)

az = (true) azimuth in degrees

alt = horizon altitude in the direction of orientation, in degrees

dec = astronomical declination in the direction of orientation, in degrees

Sources for co-ordinate information

B = Co-ordinates supplied by JB

C = Co-ordinates from Calado 2004, converted from Coordenadas Militares (Lisbon datum).

D = Co-ordinates from de Oliveira 1997 and/or Google Earth.

H = From Hoskin 2001, Table 6.2.

R = Clive Ruggles, hand-held GPS, 2005.

Table 1: Seven-stone antas ordered by their direction of orientation (azimuth). Please note that due to the presented amount of information, the following table cannot be shown on smaller devices.

| No. | N4 | Name | Group | Municipality | Dist/Prov | Country | Lat | Lat N | Long W | S | az | alt | dec | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dehesa Bollai 1 | Jerez de los Caballeros | Badajoz | Spain | 38.3 | H | 61 | 1 | +23 | ||||||||

| 2 | Contada | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 38 | 57 | 57 | 7 | 18 | 46 | D | 64 | 1 | +20½ | |||

| 3 | 17 | Huerta de las Monjas | Río Sever banks | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 24 | 18 | 7 | 18 | 8 | B | 70 | 4 | +18 | |

| 4 | 13 | Lanchas 1 | Río Sever banks | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 23 | 42 | 7 | 15 | 59 | B | 76 | 0 | +10½ | |

| 5 | Gonçala 2 | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 56 | 40 | 8 | 0 | 27 | C | 77 | 0½ | +10 | |||

| 6 | Remendo 1 | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 53 | 17 | 7 | 58 | 51 | C | 79 | 1 | +9 | |||

| 7 | Pero d’Alba | Castelo de Vide | Portalegre | Portugal | 39 | 28 | 13 | 7 | 27 | 10 | D | 79 | 2½ | +10 | |||

| 8 | 35 | Datas 1 | Santa María granite outcrop | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 20 | 0 | 7 | 13 | 36 | B | 81 | 3½ | +9 | |

| 9 | Sobral | Castelo de Vide | Portalegre | Portugal | 39 | 24 | 1 | 7 | 29 | 26 | R | 81 | 6½ | +11 | |||

| 10 | Coureleiros 3 | Castelo de Vide | Portalegre | Portugal | 39 | 26 | 48 | 7 | 28 | 2 | D | 81 | 0½ | +7 | |||

| No. | N4 | Name | Group | Municipality | Dist/Prov | Country | Lat | Lat N | Long W | S | az | alt | dec | ||||

| 11 | Pedra d’Anta | Ourique | Beja | Portugal | 37.8 | H | 82 | 0 | +6 | ||||||||

| 12 | Caeira 3 | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 53 | 5 | 7 | 57 | 13 | C | 82 | 0 | +6 | |||

| 13 | 15 | Tapada del Anta 1 | Río Sever banks | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 23 | 48 | 7 | 18 | 1 | B | 82 | 2 | +7½ | |

| 14 | Herdade do Duque | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 27 | 6 | 7 | 26 | 26 | C | 82 | 0 | +6 | |||

| 15 | Patalim | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 37 | 12 | 8 | 4 | 32 | C | 82 | 0 | +6 | |||

| 16 | Coureleiros 2 | Castelo de Vide | Portalegre | Portugal | 39 | 26 | 48 | 7 | 28 | 6 | D | 82 | 0 | +6 | |||

| 17 | Torráúo 1 | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 38 | 58 | 30 | 7 | 16 | 17 | D | 82 | -0½ | +5½ | |||

| 18 | Coureleiros 4 | Castelo de Vide | Portalegre | Portugal | 39 | 26 | 48 | 7 | 28 | 14 | D | 83 | 0 | +8 | |||

| 19 | Caeira 4 | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 53 | 3 | 7 | 57 | 9 | C | 83 | 0 | +5 | |||

| 20 | Cré 1 | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 51 | 51 | 7 | 58 | 15 | C | 83 | 3 | +5½ | |||

| No. | N4 | Name | Group | Municipality | Dist/Prov | Country | Lat | Lat N | Long W | S | az | alt | dec | ||||

| 21 | 39 | La Morera | Santa María granite outcrop | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 19 | 2 | 7 | 11 | 17 | B | 83 | 0 | +5 | |

| 22 | Olival do Monte Velho | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 39.0 | H | 84 | 3 | +6½ | ||||||||

| 23 | Silval | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 40 | 59 | 8 | 2 | 27 | C | 84 | 0 | +4½ | |||

| 24 | Coureleiros 1 | Castelo de Vide | Portalegre | Portugal | 39 | 26 | 43 | 7 | 28 | 10 | D | 84 | 0 | +4½ | |||

| 25 | Paredes | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 39 | 46 | 8 | 2 | 21 | C | 84 | 1 | +5 | |||

| 26 | Defesinhas 1 | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 38 | 47 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 23 | D | 84 | 0 | +4½ | |||

| 27 | Cré 2 | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 52 | 5 | 7 | 58 | 23 | C | 85 | 0½ | +4 | |||

| 28 | Bota 1 | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 29 | 54 | 7 | 54 | 36 | C | 85 | 0 | +3½ | |||

| 29 | Camino de los Bombonas | Barcarrota | Badajoz | Spain | 38.5 | H | 86 | 2 | +4 | ||||||||

| 30 | Hermosina | Barcarrota | Badajoz | Spain | 38.5 | H | 86 | 2 | +4 | ||||||||

| No. | N4 | Name | Group | Municipality | Dist/Prov | Country | Lat | Lat N | Long W | S | az | alt | dec | ||||

| 31 | Currais do Galhordas | Castelo de Vide | Portalegre | Portugal | 39 | 27 | 49 | 7 | 32 | 34 | D | 86 | 2½ | +4½ | |||

| 32 | 23 | Zafra 2 | Collados de Barbón | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 24 | 21 | 7 | 13 | 15 | B | 86 | 0 | +2½ | |

| 33 | 29 | Tapias 2 | Collados de Barbón | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 24 | 15 | 7 | 12 | 36 | B | 86 | 5 | +6 | |

| 34 | Claros Montes 1 | Arraiolos | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 53 | 21 | 7 | 54 | 40 | C | 86 | 1½ | +4 | |||

| 35 | Dehesa de la Muela | Mérida | Badajoz | Spain | 39.1 | H | 87 | 1 | +2½ | ||||||||

| 36 | Caeira 1 | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 52 | 33 | 7 | 56 | 57 | C | 88 | -0½ | +1 | |||

| 37 | 20 | La Barca | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 23 | 28 | 7 | 16 | 4 | B | 88 | 0½ | +1½ | ||

| 38 | Pinheiro do Campo 1 | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 36 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 13 | C | 88 | 1 | +2 | |||

| 39 | 31 | Huerta Nueva | Collados de Barbón | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 23 | 39 | 7 | 11 | 53 | B | 89 | 0½ | +1 | |

| 40 | 19 | (La) Miera | Río Sever banks | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 23 | 37 | 7 | 17 | 46 | B | 89 | 4 | +3 | |

| No. | N4 | Name | Group | Municipality | Dist/Prov | Country | Lat | Lat N | Long W | S | az | alt | dec | ||||

| 41 | Freixo de Cima 1 | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 24 | 39 | 7 | 51 | 18 | C | 89 | 0½ | +1 | |||

| 42 | Pavia | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 53 | 39 | 8 | 1 | 2 | D | 89 | 0 | +0½ | |||

| 43 | Gonçala 6 | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38.9 | H | 89 | 4 | +3 | ||||||||

| 44 | Figueirinha 2 | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 56 | 47 | 8 | 0 | 12 | C | 90 | 1½ | +0½ | |||

| 45 | Portela | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38.9 | H | 90 | 0½ | +0½ | ||||||||

| 46 | Farisoa 4 | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38.4 | H | 91 | 0 | -1 | ||||||||

| 47 | Cabeçáúo | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38.9 | H | 91 | 0 | -1 | ||||||||

| 48 | Entreáguas | Estremoz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 47 | 7 | 7 | 37 | 53 | C | 91 | 1½ | 0 | |||

| 49 | Aldeia da Mata | Crato | Portalegre | Portugal | 39 | 18 | 3 | 7 | 42 | 39 | D | 91 | 0 | -1 | |||

| 50 | Sáúo Lourenço 1 | Crato | Portalegre | Portugal | 39.2 | H | 91 | 0 | -1 | ||||||||

| No. | N4 | Name | Group | Municipality | Dist/Prov | Country | Lat | Lat N | Long W | S | az | alt | dec | ||||

| 51 | Rana | Barcarrota | Badajoz | Spain | 38.5 | H | 91 | 1 | -0½ | ||||||||

| 52 | TapadáÁes | Crato | Portalegre | Portugal | 39.2 | H | 91 | 0 | -1 | ||||||||

| 53 | Pombal | Castelo de Vide | Portalegre | Portugal | 39 | 26 | 19 | 7 | 27 | 25 | D | 92 | 3 | 0 | |||

| 54 | Torre das áüguias 1 | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 52 | 18 | 8 | 6 | 52 | C | 92 | 1 | -1 | |||

| 55 | Pasada del Abad | Rosal de la Frontera | Huelva | Spain | 38.0 | H | 93 | 1 | -2 | ||||||||

| 56 | Herdade da Anta | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38.6 | H | 93 | 1 | -2 | ||||||||

| 57 | Cré 3 | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 52 | 4 | 7 | 58 | 42 | C | 93 | 1 | -2 | |||

| 58 | 24 | Zafra 3 | Collados de Barbón | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 24 | 4 | 7 | 13 | 18 | B | 93 | 4 | 0 | |

| 59 | Monte dos Frades | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 39.0 | H | 93 | -0½ | -3 | ||||||||

| 60 | Aguiar | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38.6 | H | 94 | 0½ | -3 | ||||||||

| No. | N4 | Name | Group | Municipality | Dist/Prov | Country | Lat | Lat N | Long W | S | az | alt | dec | ||||

| 61 | Torre das áüguias 2 | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 52 | 27 | 8 | 6 | 53 | C | 94 | 1½ | -2½ | |||

| 62 | Adua 1 | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 54 | 18 | 8 | 1 | 33 | C | 94 | 0 | -3½ | |||

| 63 | Caeira 2 | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 53 | 31 | 7 | 56 | 55 | C | 94 | 0½ | -3 | |||

| 64 | Sauza 4 | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38.6 | H | 94 | 0½ | -4½ | ||||||||

| 65 | Tajeno | Barcarrota | Badajoz | Spain | 38.5 | H | 95 | 2½ | -1 | ||||||||

| 66 | Serrinha | Crato | Portalegre | Portugal | 39.0 | H | 95 | 2 | -3 | ||||||||

| 67 | Vale d’Anta | Redondo | Évora | Portugal | 38.6 | H | 95 | 0 | -4½ | ||||||||

| 68 | 25 | Zafra 4 | Collados de Barbón | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 23 | 59 | 7 | 13 | 16 | B | 95 | 5 | -1 | |

| 69 | Claros Montes 2 | Arraiolos | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 53 | 30 | 7 | 54 | 58 | C | 95 | 2 | -3 | |||

| 70 | Cebolinhos 3 | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 23 | 27 | 7 | 29 | 10 | C | 95 | 0 | -4½ | |||

| No. | N4 | Name | Group | Municipality | Dist/Prov | Country | Lat | Lat N | Long W | S | az | alt | dec | ||||

| 71 | Gonçala 1 | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 56 | 23 | 8 | 1 | 2 | C | 95 | 0 | -4½ | |||

| 72 | Bota 2 | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 30 | 11 | 7 | 54 | 37 | C | 95 | 0 | -4½ | |||

| 73 | Colmeeiro | Redondo | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 41 | 32 | 7 | 38 | 9 | C | 96 | 0½ | -4½ | |||

| 74 | Alcalaboza | Aroche | Huelva | Spain | 37.9 | B | 96 | 4 | -2½ | ||||||||

| 75 | San Blas | Barcarrota | Badajoz | Spain | 38.5 | B | 96 | 2 | -3½ | ||||||||

| 76 | Cabeças | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 40 | 59 | 7 | 53 | 46 | C | 96 | -0½ | -5½ | |||

| 77 | Vale Carneiro 1 | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 23 | 12 | 7 | 27 | 57 | C | 98 | -0½ | -7 | |||

| 78 | Sardinha | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 38.8 | H | 98 | 1 | -6 | ||||||||

| 79 | Sauza 3 | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38.6 | H | 98 | 1 | -6 | ||||||||

| 80 | Paço 1 | Redondo | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 46 | 13 | 8 | 13 | 31 | C | 98 | 0½ | -6 | |||

| No. | N4 | Name | Group | Municipality | Dist/Prov | Country | Lat | Lat N | Long W | S | az | alt | dec | ||||

| 81 | Monte Abraáúo | Sintra | Lisboa | Portugal | 38.8 | H | 98 | 0 | -6½ | ||||||||

| 82 | Olheiros | Castelo de Vide | Portalegre | Portugal | 39 | 28 | 34 | 7 | 27 | 17 | D | 99 | 10½ | 0 | |||

| 83 | Zambujalinho | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 40 | 18 | 7 | 46 | 6 | C | 99 | -0½ | -8 | |||

| 84 | 14 | Lanchas 2 | Río Sever banks | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 25 | 23 | 7 | 16 | 4 | B | 100 | 5 | -4½ | |

| 85 | Gonçala 4 | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 56 | 26 | 8 | 1 | 10 | C | 100 | 0½ | -8 | |||

| 86 | Vale de Moura 1 | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 31 | 39 | 7 | 51 | 32 | C | 100 | 1 | -7½ | |||

| 87 | 37 | Cajirón 1 | Santa María granite outcrop | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 19 | 37 | 7 | 12 | 32 | B | 100 | 0½ | -7½ | |

| 88 | Silveira | Redondo | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 40 | 32 | 7 | 31 | 8 | C | 100 | 1 | -7½ | |||

| 89 | Lapita | Barcarrota | Badajoz | Spain | 38.5 | H | 101 | 1½ | -8 | ||||||||

| 90 | Paço das Vinhas | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 37 | 24 | 7 | 52 | 43 | C | 101 | 0 | -9 | |||

| No. | N4 | Name | Group | Municipality | Dist/Prov | Country | Lat | Lat N | Long W | S | az | alt | dec | ||||

| 91 | Horta do Zambujeiro | Redondo | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 37 | 51 | 7 | 35 | 5 | C | 101 | 0½ | -8½ | |||

| 92 | Monte Ruivo | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 38.8 | H | 101 | 0 | -9 | ||||||||

| 93 | Gáfete 1 | Crato | Portalegre | Portugal | 39.4 | H | 101 | 0 | -9 | ||||||||

| 94 | 38 | Cajirón 2 | Santa María granite outcrop | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 19 | 46 | 7 | 12 | 20 | B | 101 | 5½ | -5 | |

| 95 | 22 | Zafra 1 | Collados de Barbón | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 24 | 21 | 7 | 13 | 28 | B | 101 | 6½ | -4½ | |

| 96 | Anta Grande dos AntáÁes | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 54 | 31 | 8 | 0 | 31 | C | 101 | 0½ | -8½ | |||

| 97 | Cebolinhos 2 | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 23 | 27 | 7 | 29 | 3 | C | 101 | 0 | -9 | |||

| 98 | Páúo Mole | Alandroal | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 41 | 57 | 7 | 18 | 43 | C | 102 | 4 | -7 | |||

| 99 | Candeeira | Redondo | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 42 | 16 | 7 | 33 | 11 | C | 102 | 1 | -9 | |||

| 100 | Torre das Arcas 1 | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 38 | 51 | 50 | 7 | 13 | 4 | D | 102 | -0½ | -10 | |||

| No. | N4 | Name | Group | Municipality | Dist/Prov | Country | Lat | Lat N | Long W | S | az | alt | dec | ||||

| 101 | 34 | Anta de la Marquesa | Santa María granite outcrop | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 19 | 47 | 7 | 13 | 8 | B | 102 | 0 | -9½ | |

| 102 | Gáfete 2 | Crato | Portalegre | Portugal | 39.4 | H | 102 | 0 | -9½ | ||||||||

| 103 | Lacara | Mérida | Badajoz | Spain | 39.0 | H | 102 | 0 | -9½ | ||||||||

| 104 | Casas do Canal | Estremoz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 46 | 18 | 7 | 36 | 23 | C | 103 | 2 | -9 | |||

| 105 | Farisoa 1 | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 23 | 2 | 7 | 31 | 51 | C | 103 | -0½ | -11 | |||

| 106 | Azaruja 2 | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38.6 | H | 103 | 1 | -9½ | ||||||||

| 107 | Azaruja 1 | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38.6 | H | 103 | 0 | -10½ | ||||||||

| 108 | Gorginos 3 | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38.4 | H | 103 | 0 | -10½ | ||||||||

| 109 | Barrosinha 1 | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 37 | 55 | 7 | 46 | 32 | C | 103 | 0 | -10½ | |||

| 110 | Olival da Pega 2 | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 27 | 3 | 7 | 24 | 4 | C | 103 | 2½ | -8½ | |||

| No. | N4 | Name | Group | Municipality | Dist/Prov | Country | Lat | Lat N | Long W | S | az | alt | dec | ||||

| 111 | Bernardo | Ponte de Sor | Portalegre | Portugal | 39.3 | H | 104 | 0½ | -11 | ||||||||

| 112 | Anta do Crato | Crato | Portalegre | Portugal | 39.3 | H | 104 | 2½ | -9½ | ||||||||

| 113 | Anta Grande do Zambujeiro | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 32 | 21 | 8 | 0 | 52 | D | 104 | 0½ | -11 | |||

| 114 | Monte Novo 2 | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 23 | 36 | 7 | 31 | 46 | C | 104 | 0 | -11½ | |||

| 115 | Anta Grande, Olival da Pega | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 27 | 3 | 7 | 24 | 4 | C | 104 | 3 | -9 | |||

| 116 | Freixo de Cima 2 | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 24 | 49 | 7 | 51 | 23 | C | 104 | 0½ | -11 | |||

| 117 | Sáúo Gens | Nisa | Portalegre | Portugal | 39 | 26 | 60 | 7 | 40 | 30 | D | 104 | 1 | -10½ | |||

| 118 | Farisoa 5 | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 23 | 24 | 7 | 31 | 59 | C | 104 | 0 | -11½ | |||

| 119 | Dom Miguel | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 38 | 59 | 19 | 7 | 19 | 48 | D | 104 | 2 | -9½ | |||

| 120 | 11 | Fragoso | Río Sever banks | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 26 | 23 | 7 | 18 | 0 | B | 105 | 3½ | -9½ | |

| No. | N4 | Name | Group | Municipality | Dist/Prov | Country | Lat | Lat N | Long W | S | az | alt | dec | ||||

| 121 | Sáúo Rafael 1 | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 38.8 | H | 105 | 1 | -11½ | ||||||||

| 122 | Farisoa 2 | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 23 | 10 | 7 | 31 | 59 | C | 105 | 0 | -12 | |||

| 123 | Matanga | Ponte de Sor | Portalegre | Portugal | 39.3 | H | 105 | -0½ | -12½ | ||||||||

| 124 | Sauza 1 | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38.6 | H | 105 | 1 | -11½ | ||||||||

| 125 | Milano | Barcarrota | Badajoz | Spain | 38.5 | H | 105 | 6 | -8 | ||||||||

| 126 | Monte das Oliveiras | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38.9 | H | 105 | 1 | -11 | ||||||||

| 127 | Pau | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 38 | 23 | 7 | 46 | 44 | C | 106 | -0½ | -13 | |||

| 128 | Santa Luzia | Alandroal | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 35 | 32 | 7 | 18 | 50 | C | 106 | 0½ | -12½ | |||

| 129 | 36 | Datas 2 | Santa María granite outcrop | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 20 | 2 | 7 | 13 | 36 | B | 106 | 5½ | -9 | |

| 130 | Briços | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 52 | 11 | 8 | 5 | 53 | C | 106 | 1½ | -11½ | |||

| No. | N4 | Name | Group | Municipality | Dist/Prov | Country | Lat | Lat N | Long W | S | az | alt | dec | ||||

| 131 | Cebolinhos 1 | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38.4 | H | 106 | 0 | -13 | ||||||||

| 132 | Vidigueiras 2 | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 23 | 9 | 7 | 30 | 20 | C | 106 | 0 | -13 | |||

| 133 | Galváúes | Alandroal | Évora | Portugal | 38.7 | H | 107 | 2½ | -11½ | ||||||||

| 134 | Sauza 2 | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38.6 | H | 107 | 0½ | -13 | ||||||||

| 135 | Gonçala 3 | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 56 | 38 | 8 | 0 | 32 | C | 108 | 1 | -13½ | |||

| 136 | Pedra Branca | Santiago do Cacém | Setúbal | Portugal | 38.1 | H | 108 | 1 | -13½ | ||||||||

| 137 | Defesinhas 2 | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 38.8 | H | 108 | 0 | -14½ | ||||||||

| 138 | — | Sobral | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 38 | 40 | 15 | 7 | 55 | 43 | C | 108 | 0 | -14½ | ||

| 139 | Pombal 5 | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 38.9 | H | 109 | 1 | -14½ | ||||||||

| 140 | Azinheiras | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 32 | 20 | 7 | 52 | 59 | C | 109 | -0½ | -15½ | |||

| No. | N4 | Name | Group | Municipality | Dist/Prov | Country | Lat | Lat N | Long W | S | az | alt | dec | ||||

| 141 | Paço 1 | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 23 | 54 | 7 | 27 | 47 | C | 109 | 1 | -14½ | |||

| 142 | Pena Clara 1 | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 38.9 | H | 109 | 0 | -15 | ||||||||

| 143 | 28 | Tapias 1 | Collados de Barbón | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 24 | 15 | 7 | 12 | 41 | B | 110 | 2 | -14 | |

| 144 | Lapeira | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 53 | 22 | 8 | 0 | 41 | C | 110 | 0 | -16 | |||

| 145 | Gonçala 5 | Mora | Évora | Portugal | 38.9 | H | 110 | 1 | -15 | ||||||||

| 146 | Carrascal | Agualva | Lisboa | Portugal | 38.8 | H | 110 | 1 | -15 | ||||||||

| 147 | Vale de Rodrigo 3 | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 30 | 9 | 8 | 3 | 46 | C | 110 | 0 | -16 | |||

| 148 | Forte das Botas | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 38.8 | H | 111 | 1½ | -15½ | ||||||||

| 149 | Conto do Zé Godinho | Castelo de Vide | Portalegre | Portugal | 39 | 28 | 52 | 7 | 31 | 0 | R | 111 | 2 | -15 | |||

| 150 | Quinta das Longas | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 38.9 | H | 111 | 0 | -16½ | ||||||||

| No. | N4 | Name | Group | Municipality | Dist/Prov | Country | Lat | Lat N | Long W | S | az | alt | dec | ||||

| 151 | Carcavelos | Loures | Lisboa | Portugal | 38.9 | H | 111 | 2 | -15 | ||||||||

| 152 | Monte dos Negros | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 38.9 | H | 112 | 0 | -17½ | ||||||||

| 153 | Palacio | Barcarrota | Badajoz | Spain | 38.5 | H | 112 | 4½ | -14 | ||||||||

| 154 | Vale de Moura 2 | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 31 | 7 | 7 | 50 | 53 | C | 112 | 0 | -17½ | |||

| 155 | Vale de Rodrigo 2 | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 29 | 44 | 8 | 3 | 35 | C | 112 | 0 | -17½ | |||

| 156 | Hospital | Redondo | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 39 | 43 | 7 | 36 | 3 | C | 113 | 0½ | -18 | |||

| 157 | Farisoa 7 | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 23 | 11 | 7 | 31 | 31 | C | 113 | 0 | -18 | |||

| 158 | Gorginos 1 | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 24 | 19 | 7 | 30 | 38 | C | 113 | 0 | -18 | |||

| 159 | Sáúo Rafael 2 | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 38.8 | H | 114 | 0 | -19 | ||||||||

| 160 | 18 | Corchero | Río Sever banks | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 24 | 49 | 7 | 17 | 25 | B | 114 | 0½ | -18½ | |

| No. | N4 | Name | Group | Municipality | Dist/Prov | Country | Lat | Lat N | Long W | S | az | alt | dec | ||||

| 161 | Corticeira | Estremoz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 45 | 28 | 7 | 36 | 24 | C | 116 | 10 | -13 | |||

| 162 | Vidigueiras | Redondo | Évora | Portugal | 38.6 | H | 116 | 0½ | -20 | ||||||||

| 163 | Casas Novas | Redondo | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 41 | 1 | 7 | 38 | 1 | C | 117 | 2 | -19½ | |||

| 164 | Torre das Arcas 2 | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 38.9 | H | 118 | -0½ | -22 | ||||||||

| 165 | Valmor | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 38 | 50 | 25 | 7 | 11 | 16 | D | 118 | 1 | -21 | |||

| 166 | Vidigueiras 1 | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 23 | 40 | 7 | 31 | 9 | C | 118 | 0 | -22 | |||

| 167 | Roca amador | Barcarrota | Badajoz | Spain | 38.5 | H | 121 | 2½ | -22 | ||||||||

| 168 | Melriça | Castelo de Vide | Portalegre | Portugal | 39 | 26 | 7 | 7 | 30 | 2 | D | 121 | 2½ | -22 | |||

| 169 | Barrosinha 2 | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 37 | 59 | 7 | 46 | 14 | C | 122 | -0½ | -25½ | |||

| 170 | Avessadas | Elvas | Portalegre | Portugal | 38.8 | H | 122 | 0 | -25 | ||||||||

| No. | N4 | Name | Group | Municipality | Dist/Prov | Country | Lat | Lat N | Long W | S | az | alt | dec | ||||

| 171 | Pinheiro do Campo 2 | Évora | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 35 | 50 | 8 | 4 | 57 | C | 122 | 0 | -25 | |||

| 172 | Tierra Caída 2 | Cedillo | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 38 | 41 | 7 | 31 | 25 | R | 128 | 9 | -21½ | |||

| 173 | Tierra Caída 1 | Cedillo | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 38 | 42 | 7 | 31 | 26 | R | 129 | 10 | -21½ | |||

| 174 | Monte Novo 1 | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 35 | 50 | 8 | 4 | 57 | C | T | 0 | ||||

| 175 | Monte Novo 4 | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 23 | 40 | 7 | 31 | 45 | C | T | 0 | ||||

| 176 | Vale Carneiro 5 | Reguengos de Monsaraz | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 23 | 12 | 7 | 31 | 29 | C | T | 0 | ||||

| 177 | Paço 2 | Redondo | Évora | Portugal | 38 | 23 | 36 | 7 | 27 | 51 | C | T | 0½ | ||||

| 178 | 26 | Barbón 1 | Collados de Barbón | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 23 | 29 | 7 | 12 | 25 | B | Unmeasured | |||

| 179 | 27 | Barbón 2 | Collados de Barbón | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 23 | 28 | 7 | 12 | 30 | B | Unmeasured | |||

| 180 | 21 | El Palancar | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 21 | 15 | 7 | 15 | 25 | B | Unmeasured | ||||

| No. | N4 | Name | Group | Municipality | Dist/Prov | Country | Lat | Lat N | Long W | S | az | alt | dec | ||||

| 181 | 12 | Changarilla | Río Sever banks | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 25 | 38 | 7 | 18 | 3 | B | Unmeasurable | |||

| 182 | 41 | El Caballo | Río Sever banks | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 26 | 43 | 7 | 17 | 36 | B | Unmeasurable | |||

| 183 | 40 | El Torrejón | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | Unavailable | Unmeasurable | ||||||||||

| 184 | 32 | Huerta Látigo | Collados de Barbón | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 23 | 20 | 7 | 12 | 2 | B | Unmeasurable | |||

| 185 | 30 | San Antón | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 23 | 24 | 7 | 9 | 36 | B | Unmeasurable | ||||

| 186 | 33 | Tapada del Puerto | Valencia de Alcántara | Cáceres | Spain | 39 | 23 | 38 | 7 | 14 | 20 | B | Unmeasurable | ||||

History and development

Seven-stone antas were built in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula over a period of about one thousand years spanning the 4th millennium B.C. for the burial of people belonging to a pastoralist culture.

The dolmen cluster is very consistent, with all the monuments being built with seven huge slabs of granite (orthostats) up to 3.5m high, of which the largest is the so-called backstone, which by architectural logic would be the first slab to have been put in place (Figs 3-6). The resulting polygonal chamber was approached by a corridor of variable length that can be used to date the structures: short corridor dolmens date from the beginning of the fourth millennium (c. 4000 B.C.), while the long corridor dolmens are, on average, about 800 years younger. The structures were continually reutilized: they remained ’in use‘ until the beginning of the Bronze Age, towards the end of the 3rd millennium B.C., and perhaps much later. The whole structure would have been covered by a huge mound of earth and pebbles which has nearly completely disappeared in the vast majority of cases.

The Alentejo region is exceptionally rich in megalithic remains (enclosures, menhirs, dolmens, etc.). According to recent surveys by Manuel Calado and Jorge de Oliveira (Calado 2004; de Oliveira 1997), the number of funerary megalithic monuments in the region exceeds 1000, with the number of seven-stone antas exceeding 800.

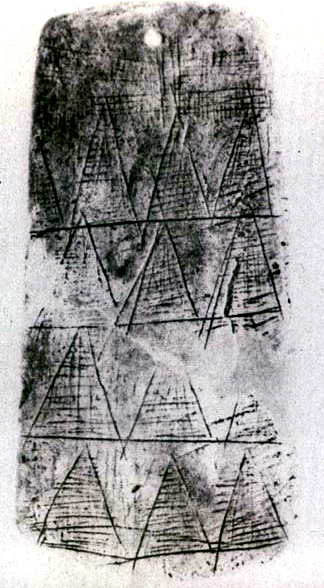

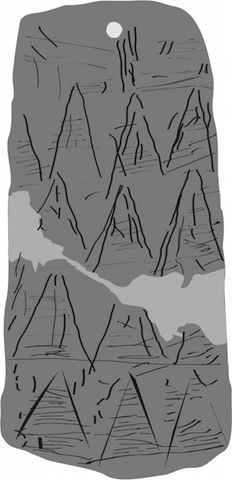

Fig. 9a. Graph showing the number of decorative elements found on 130 plate-idols discovered in megalithic monuments of the south-west of the Iberian Peninsula, including seven-stone antas. There are statistically significant peaks centred at around 12½ and 29½, close to the number of lunar (synodic) months in a seasonal (solar) year and the number of days in a lunar (synodic) month. Graph by Juan Belmonte

A consistency in the orientation of megalithic enclosures in central Alentejo implies that, like those of the seven-stone antas, these too were astronomically determined (e.g, Pimenta et al. 2009). If, as Calado (2004) has argued, the antas represent a continuity of the basic horseshoe plan of the older enclosures, then an orientation custom based upon celestial targets may have had even deeper roots in the region.

Fig. 9b. A typical plate-idol found precisely in one of the dolmens of Valencia de Alcántara. Photograph adapted from Bueno Ramírez (1988)

The dolmens of the region of Valencia de Alcántara, on the Spanish side of the border, were studied in detail in the 1980s by Jorge de Oliveira and others. Some of them were excavated, this being the main objective of the PhD thesis of Primitiva Bueno, of the University of Alcala de Henares, published in 1988, and further archaeological and restoration work has been carried out since that date.

Interestingly, a century before the quantitative fieldwork of Hoskin and his collaborators, José Leite de Vasconcellos, a Portuguese archaeologist and ethnologist, argued in his book ReligiáÁes da Lusitania, published in 1897, that the orientations of dolmen entrances, which were ’very frequently facing East‘, might have been related to a sun cult.

Justification for inscription

Comparative analysis

The seven-stone antas found in the central Alentejo region in Portugal and the adjacent border provinces of the Extremadura region in Spain represent one of the largest and best-preserved groups of megalithic monuments in the Iberian Peninsula. The great majority are built with granite slabs, frequently including a corridor. The concentrations around Évora and Valencia de Alcántara are easily located, representative, and contain some of the most impressive individual examples.

Many other groups of European later prehistoric monuments show patterns of orientation that were certainly determined astronomically and in most cases were probably related to the sun (Hoskin 2001, Ruggles 2010).

The range of astronomical declinations of the horizon points towards which the seven-stone antas face is from –24° to +24° (see Table 1 and Fig. 7). This corresponds to the range of declinations reached by the sun over the course of the year; in other words, each monument is oriented towards a point where the sun rises at some time in the year, with the various monuments effectively covering the entire range. Hence, applying Ockham’s Razor, this appears to be very strong indication of a custom of orientating monuments towards sunrise, with no particular preference for specific times within the seasonal year. Among the many groups of European later prehistoric monuments, only the seven-stone antas manifest a clear and consistent practice of orientation related specifically to the rising arc of the sun over the course of a year. They are quite exceptional in this respect.

Integrity and/or authenticity

As regards the astronomical significance of this group of monuments, a critical issue is the extent to which the intended, or original, direction of orientation is accurately represented and well preserved.

Fig. 10. Coureleiros 4 (no. 18 in Table 1), as seen in 2005. The chamber has completely collapsed. Photograph © Clive Ruggles

Fig. 11. (La) Miera (no. 40 in Table 1). One of the authors (JB) is measuring the horizon altitude in the direction of the only surviving corridor orthostat. This would give a loose, but still valid, orientation of the partly destroyed dolmen. Photograph courtesy of Margarita Sanz de Lara

Fig. 12. Cajirón 2 (no. 94 in Table 1) before (top) and after (bottom) excavation and restoration; in this particular case, the reconstruction was carried out

with much caution and the orientation of the monument was preserved. Photographs © Juan Belmonte (top) and Clive Ruggles (bottom)

The sites are in various states of repair. Some are well preserved (Figs 3, 5, 6). In other cases the chamber has collapsed leaving only the backstone, the stone put in place first, but the direction perpendicular to this backstone still gives a reliable estimate of the orientation (see Fig. 10). In other cases just a few stones are preserved, often the backstone or some stones of the corridor, but this still permits a potential measurement of the orientation (see Fig. 11).

Some of the Spanish examples, such as Cajirón 2 (see Fig. 12), have been reconstructed since their orientations were determined in the 1990s. In Portugal, especially near Évora, Montemor-o-Novo and Castelo de Vide, a limited number of seven-stone antas have been cleaned, excavated and/or restored.

A few of the antas in the Valencia de Alcántara group have been restored but where this has happened it has been done cautiously, using the original slabs found scattered in situ. Thus very little ’reconstruction‘ has taken place and only a few of the stones have been moved back to their ’original‘ position. Where, as at Cajirón 2 (Fig. 12), the capstone has been replaced on top of the structure, this has been achieved without altering its overall orientation.

Criteria under which inscription might be proposed

Criterion (iii). The seven-stone antas bear unique testimony to a cultural practice dating back between five and six thousand years whereby tombs were oriented upon the rising position of the sun. In doing so, they bear exceptional witness to prehistoric cultural traditions and beliefs relating death and ancestors to the sun and seasonality. They represent the oldest group of monuments on the planet that provide statistically defensible evidence of practices and beliefs linking monumental constructions with the skies.

Suggested statement of OUV

The seven-stone antas are a distinctive form of megalithic tomb constructed more than 5000 years ago. They represent the oldest group of monuments on the planet that provide statistically defensible evidence of practices and beliefs linking monumental constructions with the skies. The 177 examples whose principal orientation has been reliably determined all, without exception, face within the arc of sunrise (the part of the horizon where the sun rises at some time during the year). The extraordinary consistency in an orientation pattern that characterises a set of monuments scattered over hundreds of kilometres provides an exceptionally clear indication of an astronomical relationship so significant to the builders that it was implemented unswervingly during the construction of hundreds of monuments, possibly over a period spanning several centuries. This offers a unique insight into the minds of the builders of some of the earliest later prehistoric monuments on the planet still conspicuously visible in today’s landscape.

State of conservation and factors affecting the property

Present state of conservation

Almost 200 seven-stone antas are known but somewhat fewer than this number are in a sufficiently good state of preservation that alignments studies can be performed. The monuments have been re-used through history, and even today, for purposes varying from pig shelters to Christian chapels (see Fig. 13).

Fig. 13 Left/Top. Pombal (no. 53 in Table 1). Located in the Portuguese countryside, this anta has been used as a pig-shelter, which has in fact ensured its preservation. Right/Bottom Pavia (no. 42 in Table 1). This anta, in the centre of the village of Pavia, was converted in the 17th century into a Christian chapel, the Capela de Sáúo Dinis, which is still in use. Photographs courtesy of Margarita Sanz de Lara.

About 40% of the granite-built seven-stone antas (dolmens) of Valencia de Alcántara (Spain) are considered to be in either an excellent or a good state of preservation (see Table 3.2); this number rises to 52% when only the dolmens in the 3 groups shown in Fig. 2 (I - Collados de Barbón; II - Río Sever banks; III - the granite outcrop of Santa María de la Cabeza) are taken into consideration. Tapias 1, Zafra 3 and Anta de la Marquesa are among the best preserved, and most impressive, dolmens in the Iberian Peninsula.

Table 2: State of preservation of the granite-built seven-stone antas of Valencia de Alcántara (Spain). The table presents the reference number and name as in Table 1. The site number shown in Fig. 2 is also given, in brackets. Please note that due to the presented amount of information, the following table cannot be shown on smaller devices.

| State of preservation | Río Sever banks group | Collados de Barbón group | Santa María granite outcrop group | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent | 3 (17) Huerta de las Monjas 13 (15) Tapada del Anta 1 | 58 (24) Zafra 3 143 (28) Tapias 1 | 101 (34) Anta de la Marquesa 94 (38) Cajirón 2 | |

| Good | 4 (13) Lanchas 1 84 (14) Lanchas 2 120 (11) Fragoso | 39 (31) Huerta Nueva 68 (25) Zafra 4 | 8 (35) Datas 1 129 (36) Datas 2 | 37 (20) La Barca |

| Moderate | 40 (19) (La) Miera 160 (18) Corchero | 32 (23) Zafra 2 178 (26) Barbón 1 179 (27) Barbón 2 | 87 (37) Cajirón 1 | 180 (21) El Palancar |

| Poor | 181 (12) Changarilla 182 (41) El Caballo | 33 (29) Tapias 2 95 (22) Zafra 1 184 (32) Huerta Látigo | 21 (39) La Morera | 183 (40) El Torrejón 185 (30) San Antón 186 (33) Tapada del Puerto |

| Destroyed | — (16) Tapada del Anta 2 |

Factors affecting the property

Development pressures (4.b.i)

Generally, the monuments are scattered in a rural landscape and there are few developmental pressures. For example, Valencia de Alcántara is a small town of nearly 7000 inhabitants surrounded by a “dehesa” landscape, typical for Extremadura. The climate is mild and the land use is mainly agricultural with a small amount of pastoral (sheep, Iberian pigs and cattle). Field clearance remains a major threat to the conservation of the antas, the destruction of some of which has been reported by archaeologists. In some areas it has been estimated that one third of the monuments have disappeared in the last 50 years (Leonor Rocha and Cândido Marciano da Silva, priv. comm).

Visitor/tourism pressures (4.b.iv)

Being a set of small, isolated monuments located in a variety of land-use situations, the seven-stone antas face various potential threats, but they are generally safe from the damage that might be caused by large numbers of visitors.

Even in the Valencia de Alcántara area, where the granite-built seven-stone antas constitute one of the major tourist attractions (see below), visitors only put small pressure upon the sites.

Protection and management

Ownership

The vast majority of the seven-stone antas are located on privately owned farmland.

Protective designation

In Portugal, the antas are protected as classified archaeological sites by the Ministério da Cultura under Heritage Law no. 107/2001. A number of them have been classified as National Monuments for many years, in most cases since the first half of the 20th century, and the archaeological guide published in 1994 by Ana Paula dos Santos lists 21 such sites.

In Spain, the antas are Bienes de Interés Cultural (BIC) protected under Articles 14–25 of Law 16/1985 on Spanish Historical Heritage.

Visitor facilities and infrastructure

Several municipalities have reached agreements with the owners so that free access (servidumbre de paso, permission to cross) exists to most of the sites. In particular, this is true for all the dolmens in certain localities, such as Valencia de Alcántara and several villages of Portugal, especially near Évora. Nonetheless, in many other places, notably in Portugal, the antas are only accessible to the public with the landowner’s permission.

All of the three groups of well-preserved dolmens within the municipality of Valencia de Alcántara (see Fig. 3.2) are open to visitors, easily reachable (being located close to well established tracks), and clearly marked. High-quality rural tourism is an important source of income in the Valencia de Alcántara area (see, e.g., http://www.virgencabeza.com/espanol/Dolmenes.htm) with environmentally aware visitors. There is a special agreement between the municipality’s Consejería de Cultura and the landowners so that free access to the dolmens is allowed in every case, providing that visitors apply minimum care and observe basic procedures (close fences, avoid jumping walls, etc.). In some areas, such as the Zafra/Tapias sector, to the east of the village, and in the Aceña de la Borrega area to the south, special tourist routes have been arranged and appropriately marked, making tours with an adequate guide/book a real pleasure for interested visitors. The municipality can arrange visits for groups under special circumstances upon demand.

In Portugal, especially near Évora, Montemor-o-Novo and Castelo de Vide, a limited number of seven-stone antas have been cleaned, excavated and/or restored, and are accessible to the general public. Four tours are managed by the Municipal Museum of Coruche near Montemor-o-Novo (áügua Doce, Azinhal, Vale de Gatos e Chapelar, and Martinianos). At one entrance a panel invites visitors to follow four tracks through the numerous antas (about 25) of the region (see Fig. 3.14). However, in the same fence a small sign in red prohibits public entry. In practice, visits are authorized but only in small groups, organized and guided by the Museum.

Fig. 14. Sign marking the entrance to one of the four megalithic tours run by the Municipal Museum of Coruche. Photograph © Luís Tirapicos

Presentation and promotion policies

A number of local authorities, including those at Évora, Castelo de Vide, Marváúo, Montemor-o-Novo, Cedillo and Valencia de Alcántara, have produced booklets, pamphlets and web pages for tourists and more interested visitors, with information about the nature and whereabouts of some of the sites in their area.

The Historic Centre of Évora, inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1986, is located in the heart of one of the major concentrations of antas in the Alentejo. The region has also seen important investments in rural tourism, in particular near the great lake created by the Alqueva dam, around which the first dark sky reserve in Portugal was established: this was also the first site in the world to receive “Starlight Tourism Destination” certification.

Documentation

Most recent records or inventory

Some of the seven-stone antas in both countries have been excavated. The orientations of the seven-stone antas were first systematically measured by Michael Hoskin together with Spanish and Portuguese collaborators between 1994 and 1998, as part of a 12-year fieldwork campaign measuring the orientations of many hundreds of tombs and temples in the western Mediterranean. An extensive scientific bibliography has been produced on the topic.

Bibliography

- Belmonte, J.A. and Belmonte J.R. (2002). Astronomía y cultura en el megalitismo tempranote la Península ibérica: los dólmenes de Valencia de Alcántara, in Arqueoastronomía hispana, edited by J.A. Belmonte. Madrid: Equipo Sirius, 99-112.

- Belmonte, J.A. and Hoskin, M. (2002) Reflejo del cosmos: atlas de arqueoastronomía del Mediterráneo occidental. Madrid: Equipo Sirius.

- Calado, M. (2004). Menires do Alentejo Central. Génese e evoluçáúo da paisagem megalítica regional. Lisboa: Universidade de Lisboa [Ph.D thesis].

- Cardoso, J.L. (2002). Pré-História de Portugal. Lisboa: Editorial Verbo.

- González García, A.C. and Belmonte, J.A. (2010). Statistical Analysis of Megalithic Tomb Orientations in the Iberian Peninsula and Neighbouring Regions. Journal for the History of Astronomy 41, 225-38.

- Bejarano, F. (1992). Guía del conjunto megalítico de Valencia de Alcántara.Valencia de Alcántara: Ayuntamiento de Valencia de Alcántara.

- Bueno Ramírez, P. (1988). Los Dólmenes de Valencia de Alcántara. Madrid: Subdirección General de Bellas Artes y Arqueología.

- Bueno Ramírez, P. and Vázquez Cuesta, A. (2008). Patrimonio arqueológico de Valencia de Alcantara. Estado de la cuestión. Valencia de Alcántara: Ayuntamiento de Valencia de Alcántara.

- Gomes, C.J., Sarantopoulos, P., Gomes, M. V., Calado, M., de Oliveira, J., Mascarenhas, J.M., Barata, F.T., Pinto, I.V., Viegas, C., Dias, L.F. (1997). Paisagens arqueológicas a oeste de Évora. Évora: Câmara Municipal de Évora.

- Gonçalves, V.S. (1999). Reguengos de Monsaraz – territórios megalíticos. Lisboa: Museu Nacional de Arqueologia.

- Hoskin, M. (2001). Tombs, Temples and their Orientations. Bognor Regis: Ocarina Books.

- Leisner, G and Leisner V. (1956) Die Megalthgräber der Iberischen Halbinsel. Der Western. Madrider Forschungen I:1.

- Oliveira, C., Rocha, L., da Silva, C.M. (2007). Megalitismo funerário no Alentejo Central – arquitectura e orientaçáÁes: o estado da questáúo em Montemor-o-Novo. Revista Portuguesa de Arqueologia 10, nᵒ 2, 35-74.

- de Oliveira, J. (1997). Monumentos megalíticos da bacia hidrográfica do Rio Sever. Marváúo: Ibn Maruán.

- de Oliveira, J. (1998). Antas e Menires do Concelho de Marváúo. Ibn Maruán 8, 13-47.

- de Oliveira, J., Pereira, S., Parreira, J. (2007). Nova Carta Arqueológica do Conselho de Marváúo. Marváúo: Ibn Maruán.

- Pimenta, F., Tirapicos, L., Smith, A. (2009). A Bayesian Approach to the Orientations of Central Alentejo Megalithic Enclosures. Archaeoastronomy 22, 1-20.

- Rocha, L. (2010). As origens do megalitismo funerário alentejano. Revisitando Manuel Heleno. Promontoria 7/8.

- Ruggles, C. (2010). Later prehistoric Europe. In Ruggles. C. and Cotte, M. (eds), Heritage Sites of Astronomy and Archaeoastronomy in the Context of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention: a Thematic Study, pp. 28–35. Paris: ICOMOS–IAU.

- dos Santos, A.P. (1994). Monumentos megalíticos do Alto Alentejo. Lisboa: Fenda.

- da Silva, C.M. (2004). The Spring Full Moon. Journal for the History of Astronomy 35, 475-478.

- da Silva, C.M. (2010). Neolithic Cosmology: The Equinox and the Spring Full Moon. Journal of Cosmology 9, 2207-2216.

- Vasconcellos, J.L. (1897). ReligiáÁes da Lusitania. Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional.

No multimedia content published

Currently there is no multimedia content published for this case study