Category of Astronomical Heritage: tangible immovable

Maragheh observatory, Iran

Presentation

Geographical position

Maragha, North-west Iran

Location

Latitude 37° 23′ 46″ N, longitude 46° 12′ 33″ E. Elevation 1560m above mean sea level.

General description

Fig. 1. An aerial view of the observatory site. After Parviz Vardjavand, Kavosh-e Rasadkhaneh-e Maragha. Tehran: Amirkabir Publications, 1987

The Maragha Observatory has a unique place in the history of medieval astronomy. It represents a new wave of scientific activities in the Islamic world in the mid 13th century, it had a key role in the development of some sophisticated pre-Copernican non-Ptolemaic systems for explaining the planetary motions, and it was the model for several observatories that were built in Persia, Transoxiana, and Asia Minor up to the 17th century. As an influential institution that was not devoted solely to astronomy, the Maragha Observatory revived advanced scientific studies during what is normally considered the period when science declined in Islam. Ideas initiating from the Maragha School impacted well beyond the Islamic territories and influenced the astronomical revolution of the 16th century.

Brief inventory

Fig. 2. The observatory site before (top) and after (bottom) the first stage of excavation. After Parviz Vardjavand, Kavosh-e Rasadkhaneh-e Maragha. Tehran: Amirkabir Publications, 1987

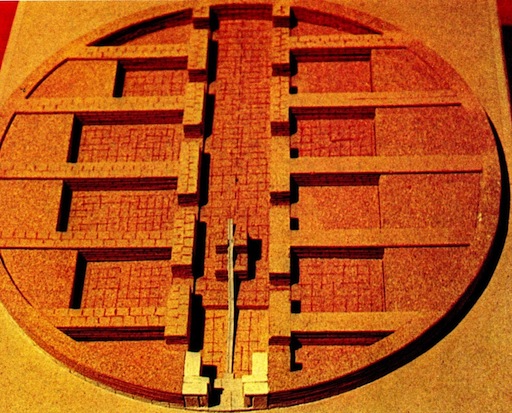

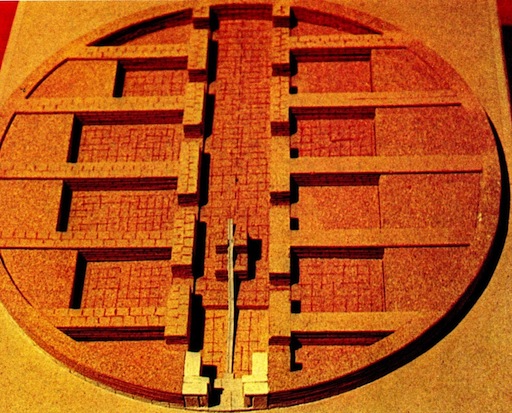

Fig. 3. Model replica of the observatory site. After Parviz Vardjavand, Kavosh-e Rasadkhaneh-e Maragha. Tehran: Amirkabir Publications, 1987

Fig. 4 Top:. The remnants of the mural quadrant, the observatory’s main instrument. Bottom: Auxiliary observational sites close to the main building of the observatory. After Parviz Vardjavand, Kavosh-e Rasadkhaneh-e Maragha. Tehran: Amirkabir Publications, 1987

The central structure, which is assumed to be the main building of the observatory, is circular. Its diameter is 22m and the base of its enclosing wall is 80 cm thick. A 1.5m-wide entrance opens into a 3.1m-wide corridor that marks the meridian line and contains the remains of the mural quadrant, of which 5.5m has survived. On each side of the central corridor are 6 rooms, the pair at each end being smaller than the rest. Outside the main building towards the south, south-east and north-east are five circular constructions. These were the places where the smaller observational instruments were once mounted. There is also a separate building, with an area of 330m², which is assumed to be the library of the observatory. In addition, archaeologists have discovered a unit where the metal parts of the instruments were cast and assembled.

History

The construction of the Maragha Observatory commenced in 1259 under the patronage of Genghis Khan’s grandson Hūlāgū. Its director was Nas─½r al-D─½n Tūs─½ (1201-1274), an eminent Persian mathematician, astronomer and philosopher whose reputation spread as far as China and whom Hūlāgū had appointed as one of his advisors. The observatory was in fact a scientific institute, with a main building for the observational equipment, some auxiliary buildings, and accommodation quarters. In the observatory, there was a library which is said to have contained about 400,000 volumes. A team of astronomers, most of whom were invited from different parts of the Islamic world, were responsible for the design and construction of the astronomical instruments, as well as for conducting observations and performing calculations.

According to a text written by Mu’ayyad al-D─½n al-‘Urd─½ (d. 1266), one of the chief astronomers and instrument designers of the observatory, its astronomical equipment included a mural quadrant with a radius of about 40m, a solstitial armilla, an azimuth ring, a parallactic ruler (triquetrum), and an armillary sphere with a radius of about 160cm.

After the death of Nas─½r al-D─½n Tūs─½ in 1274, the Maragha observatory was supervised by his son and remained active until the end of the 13th century. However, following the death of Hūlāgū in 1265 and his son Abāqā in 1282, it lost its powerful patrons and had become inactive by the beginning of the 14th century. Despite this, we have reports that Ghāzān Khān, who reigned from 1295 to 1304, visited the Maragha Observatory several times, probably using it as a model for his own observatory in Tabriz (which has not survived).

Cultural and symbolic dimension

Maragha observatory is the place where Tūsī, with the cooperation of a number of renowned astronomers, mathematicians, and instrument makers, compiled one of the most important Islamic astronomical tables, the Īlkhānī Zīj, completing this work in 1272. The astronomers at Maragha also carried out complicated programmes in observational and computational astronomy to update the Ptolemaic parameters.

In addition, the Maragha Observatory represents a turning point in the development of alternatives to Ptolemy’s planetary models that were compatible with Aristotelian cosmological principles. These elaborate models, together with further innovations developed at the Samarqand Observatory and later at Damascus, found their way to Europe and formed a critical part of the mathematical tools that enabled Copernicus to create the heliocentric model of the universe.

Authenticity and integrity

The location of the observatory is essentially an archaeological site with visible material remains and ruins of ancient constructions.

Management and use

Present use

Apart from a few star parties and occasional visits to the site by scholars, there is little activity at the site.

State of conservation

In recent years a dome-shaped shelter has been constructed above the remnants to preserve them from further destruction.

Protection

Since the Islamic Revolution in Iran (1978), the nearby Tabriz University has been responsible for the management and protection of the Maragha site.

Context and environment

The observatory is located at the top of a hill to the west of Maragha.

Archaeological / historical / heritage research

The site of the observatory was excavated in the 1970s by an Iranian archaeological team supervised by P. Vardjavand. They recovered the remnants of 16 original constructional units: some are located at the central observatory building, while others are assumed to be auxiliary structures. There have not been any further investigations since this time.

Management, interpretation and outreach

There is no indication of a general plan for the future of the site.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles)

- Saliba, George (1987). ’The role of Maragha Observatory in the development of Islamic astronomy: a scientific revolution before the Renaissance‘, Revue de Synthèse, 108, 361-73.

- Vardjavand, Parviz (1987). Kavosh-e Rasadkhaneh-e Maragha. Tehran: Amirkabir Publications.

No multimedia content published

Currently there is no multimedia content published for this case study