Category of Astronomical Heritage: tangible immovable

Akademie Sternwarte Berlin, Germany

Description

Geographical position

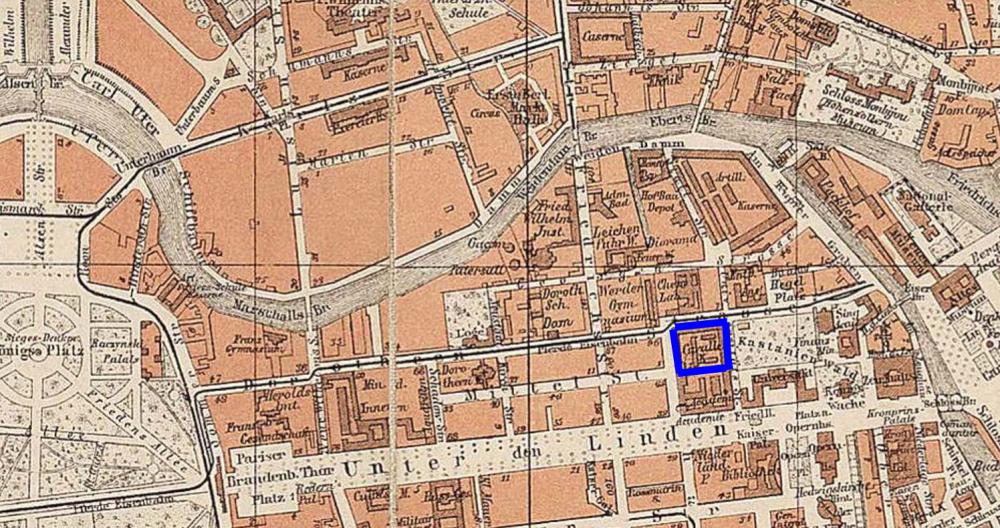

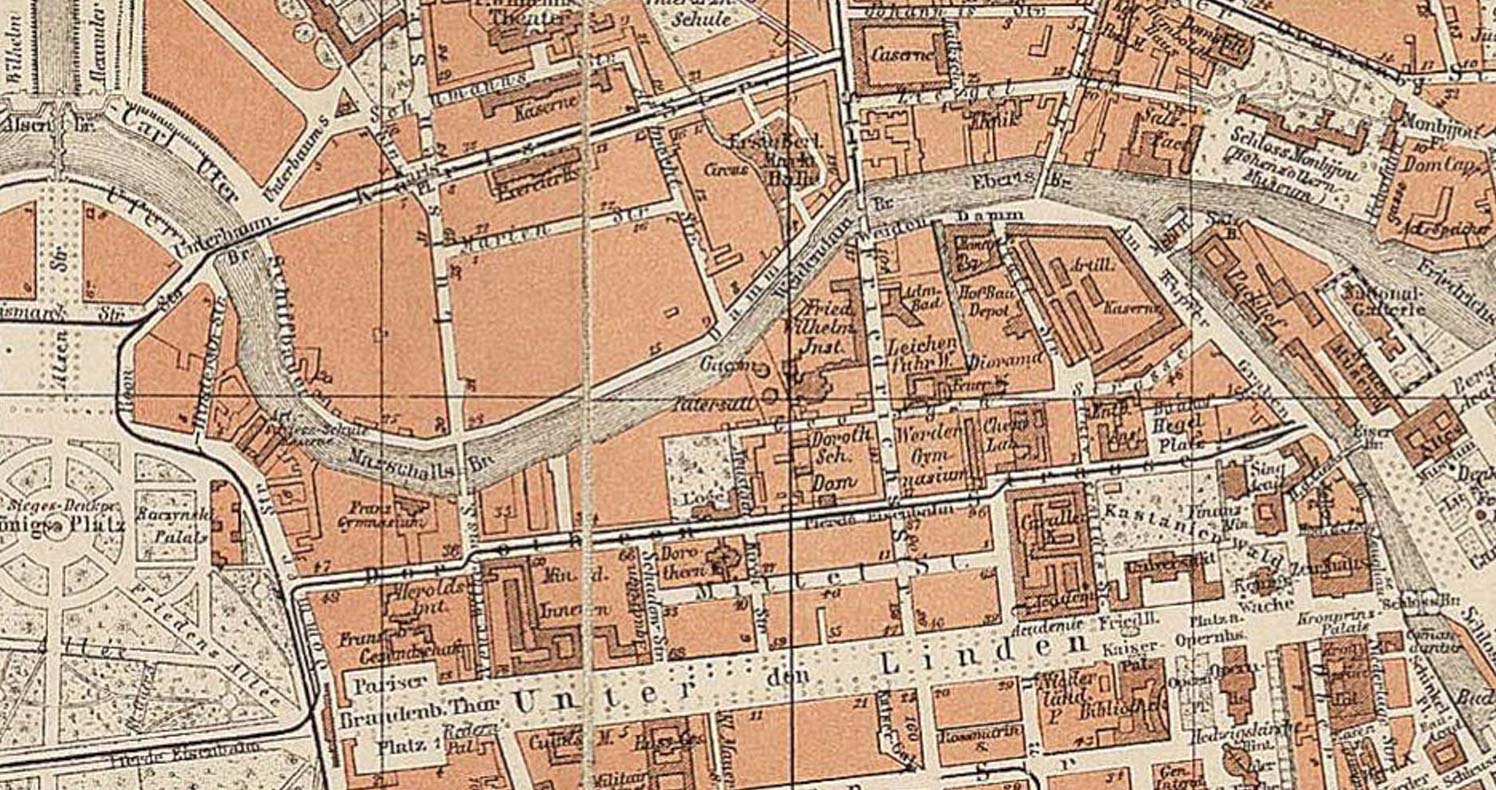

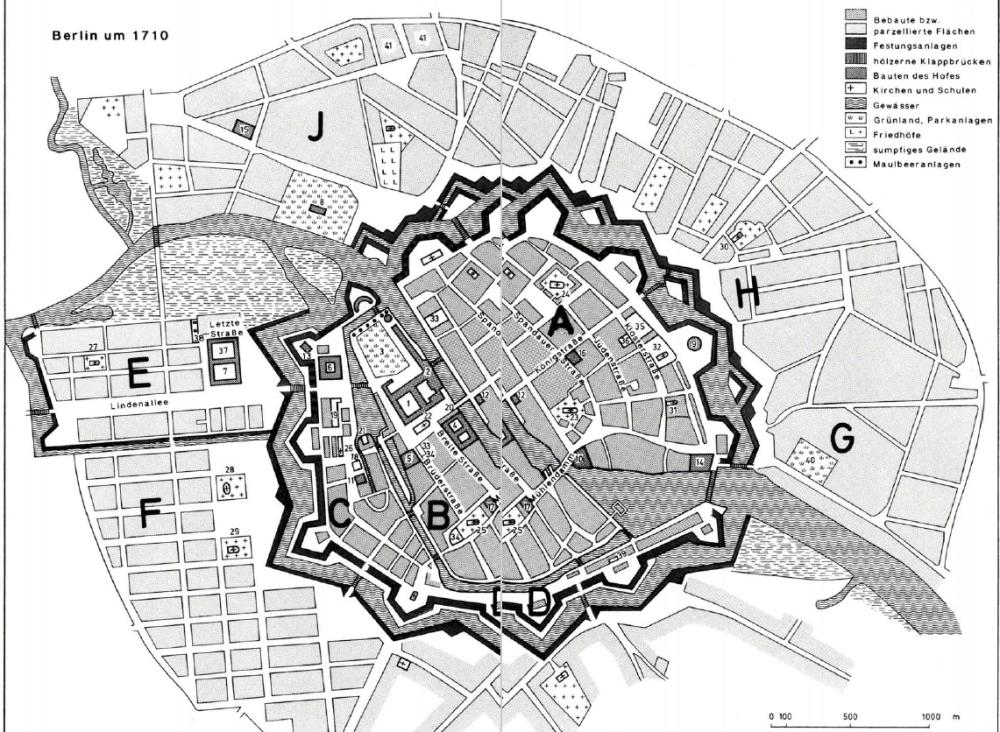

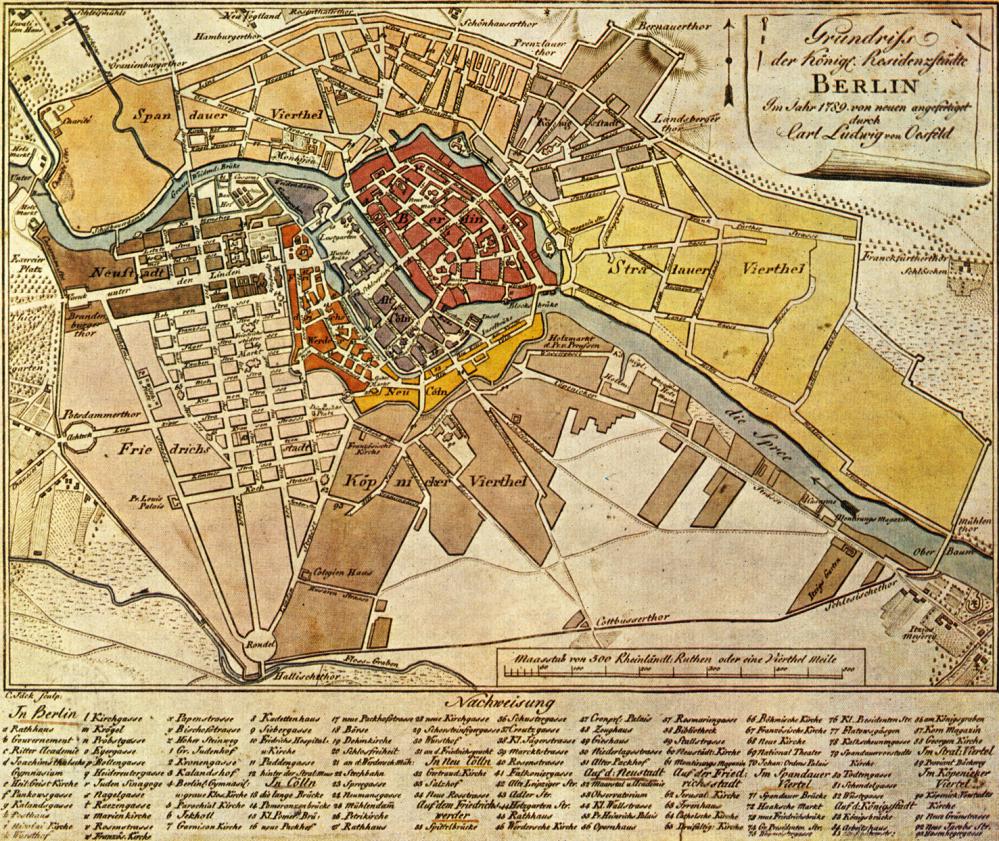

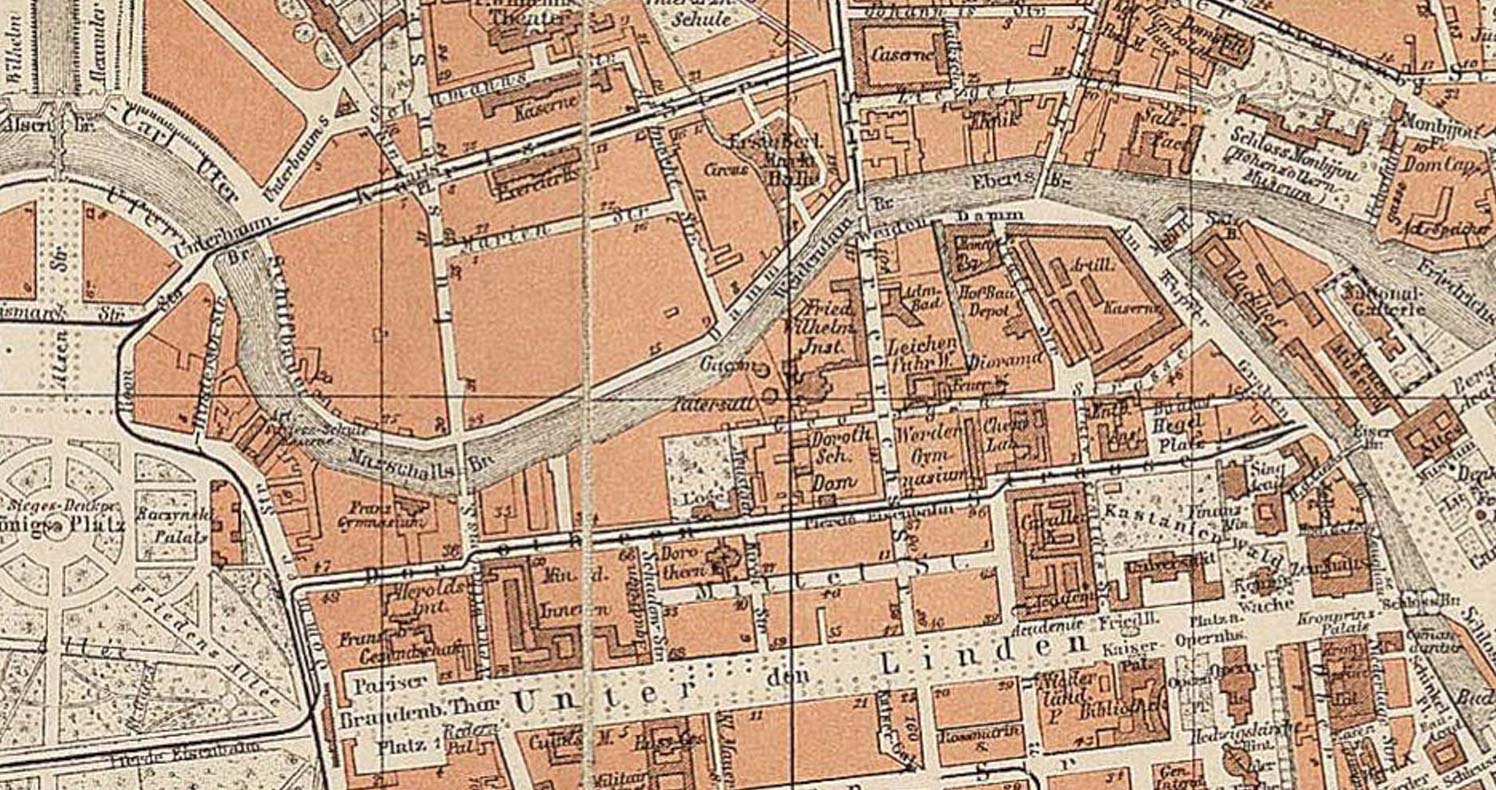

Akademie Sternwarte (Academy Observatory) auf dem Marstall (Royal Stables), Dorotheenstrasse 27, Berlin (1711), Germany

(today State University Library, back entrance, Stadtbezirk Mitte)

Cf. Observatories in Berlin and Potsdam:

- Akademie Sternwarte auf dem Marstall (Royal Stables), Dorotheenstrasse, Berlin (1711)

- New Royal Observatory Berlin (Königliche Sternwarte zu Berlin), Schinkel (1835)

- Astronomisches Recheninstitut Berlin (after WWII moved to Heidelberg)

- Babelsberg Observatory, Berlin University Observatory, Potsdam-Babelsberg

- Astrophysical Observatory (APO) Potsdam, Telegraphenberg (1874)

- Einstein Tower, Potsdam (1924)

Cf. Private and Public Observatories and Planetariums:

- Kroseck’s Private Observatory Berlin (1706), Wallstraße 72, Neu-Cölln

- Wilhelm Beer’s (1797--1850) Private Observatory (1829) with a 9.5-cm-Refractor in Tiergarten, Behrenstraße

- Archenhold Observatory with the "longest" moveable refractor on earth (21m), Alt-Treptow 1, Treptower Park, 12435 Berlin (1896), IAU code 604

- Wilhelm-Foerster-Observatory with Planetarium, Munsterdamm 90, 12169 Berlin (1947)

- Zeiss Gross-Planetarium (Zeiss Major Planetarium), Prenzlauer Allee 80, Thälmann-Park, 10405 Berlin (1987)

Location

Latitude 52.520048 N, longitude 13.391986 E. Elevation 38m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code

--

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage

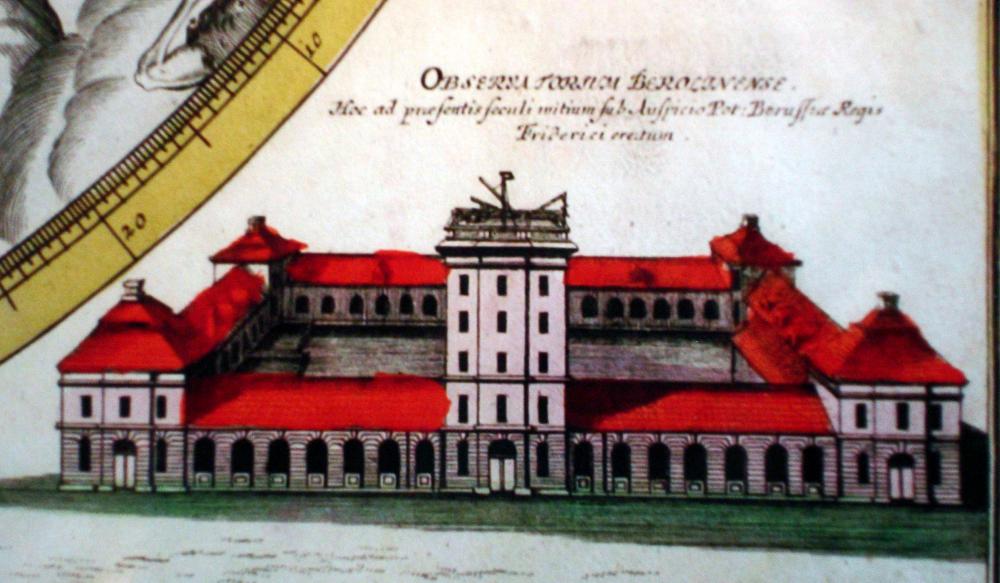

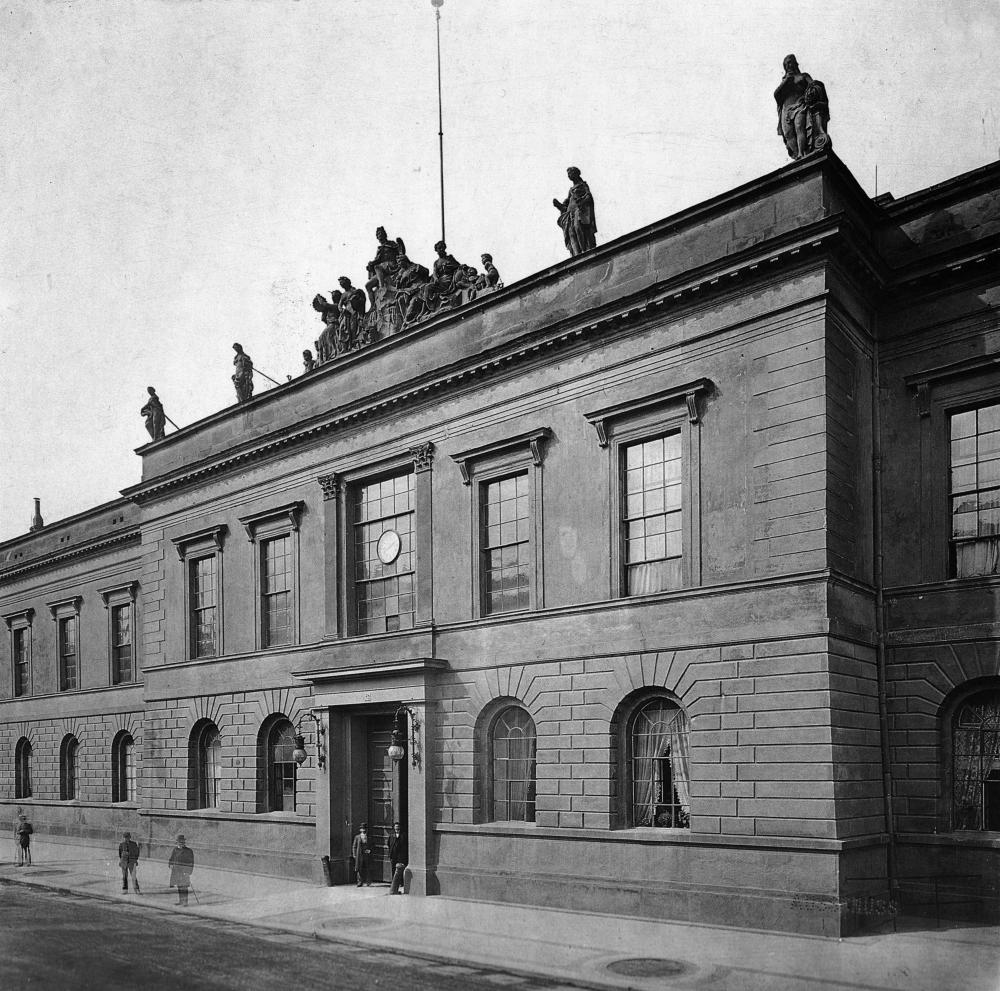

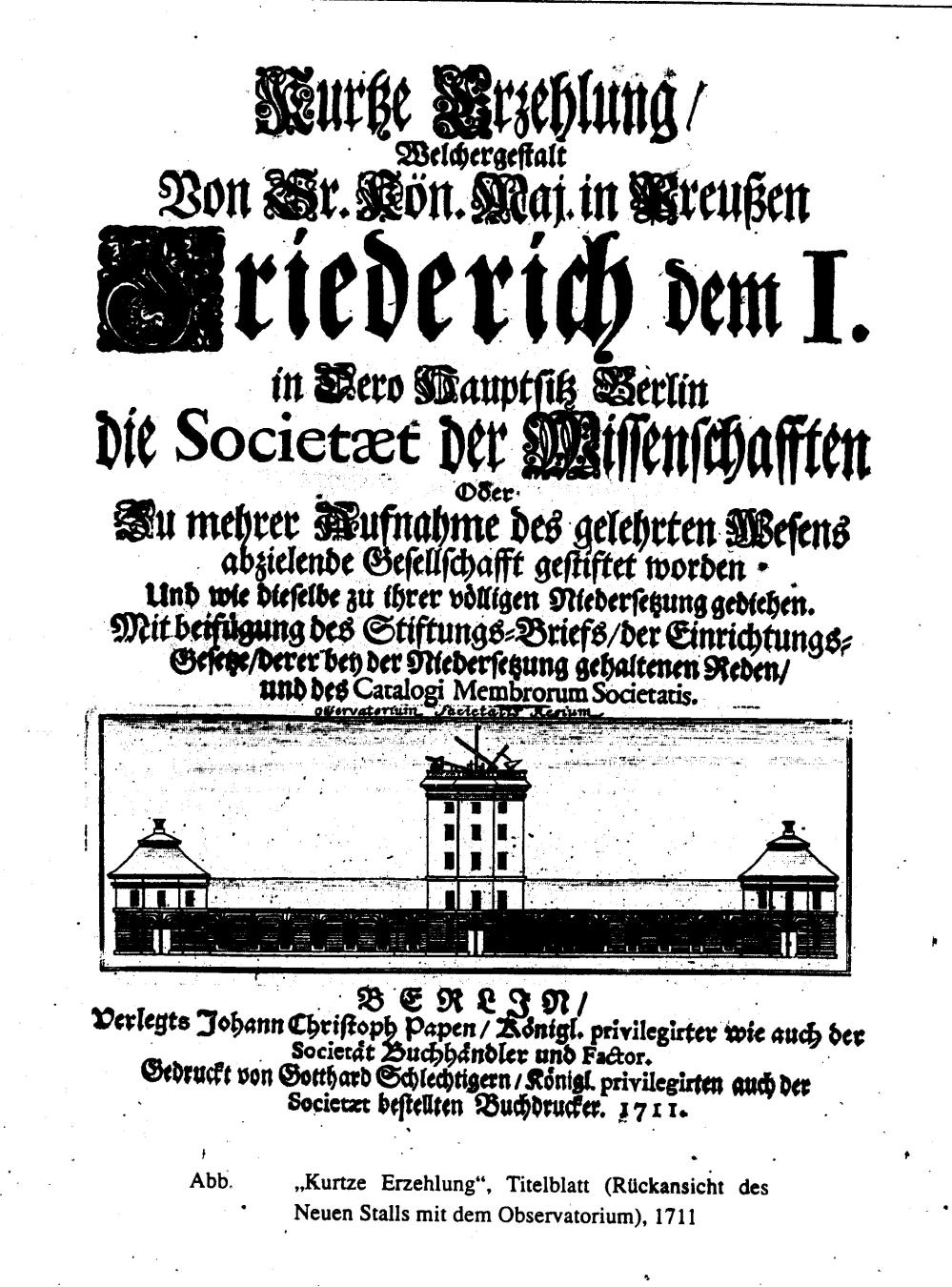

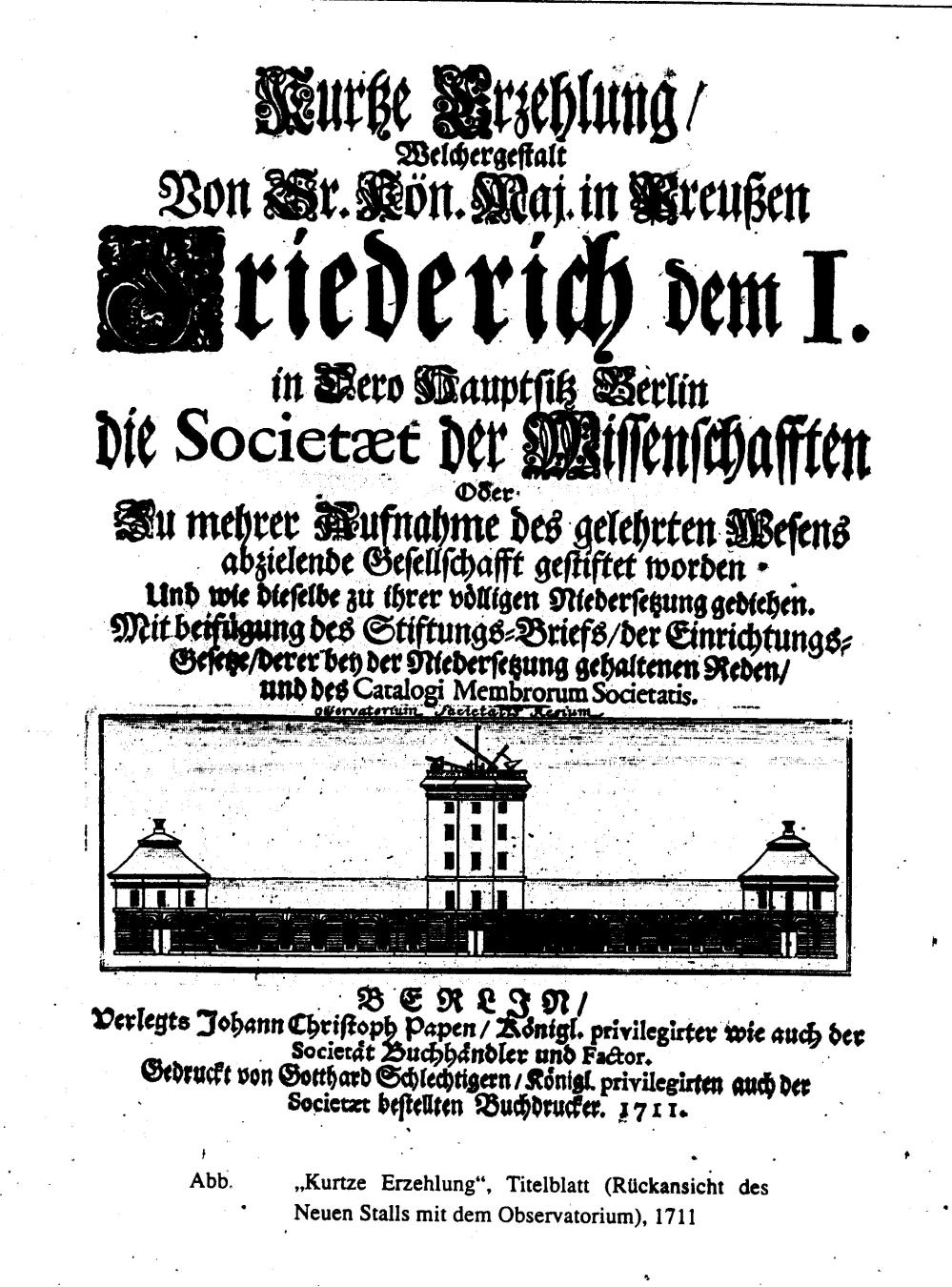

Fig. 1a. The Royal Stables (Marstall) and the Academy Observatory 1711 (Festschrift zur Eröffnung der Akademie)

Fig. 1b. Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz (1646--1716) initiated in 1700 the "Kurfürstlich Brandenburgische Sozietät der Wissenschaften" (Electoral Brandenburg Society of Sciences) (painting by Christoph Bernhard Francke, 1695, CC)

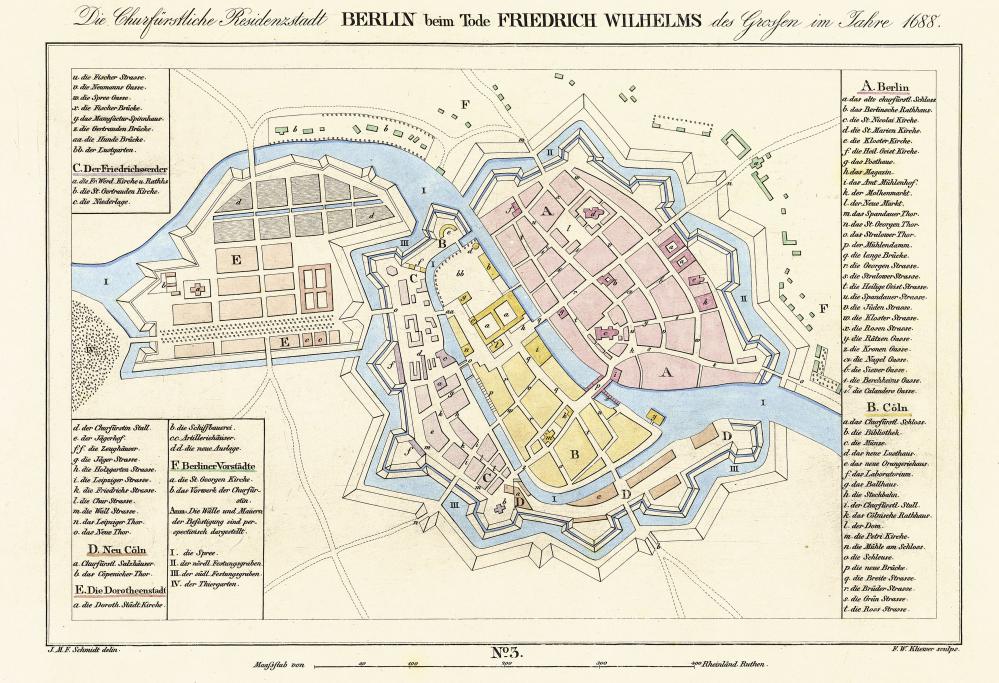

The Royal Stables (Marstall) for 200 horses were erected in 1687/88 by Johann Arnold Nering (1659--1695) as Kurfürstlich-Brandenburgischer Oberbaumeister (Electoral Brandenburg master builder). The building was raised by one floor in 1695 to 1697 for the Academy of Arts.

As a replacement for the wing "Unter den Linden", that burned out in 1743, Johann Boumann d.Ä [Jan Bouman]. (1706--1776) built from 1747 to 1749 a new building. In its Western part, moved the Academy of Sciences (demolished in 1903), in the Eastern part (demolished in 1908) moved the Academy of Arts.

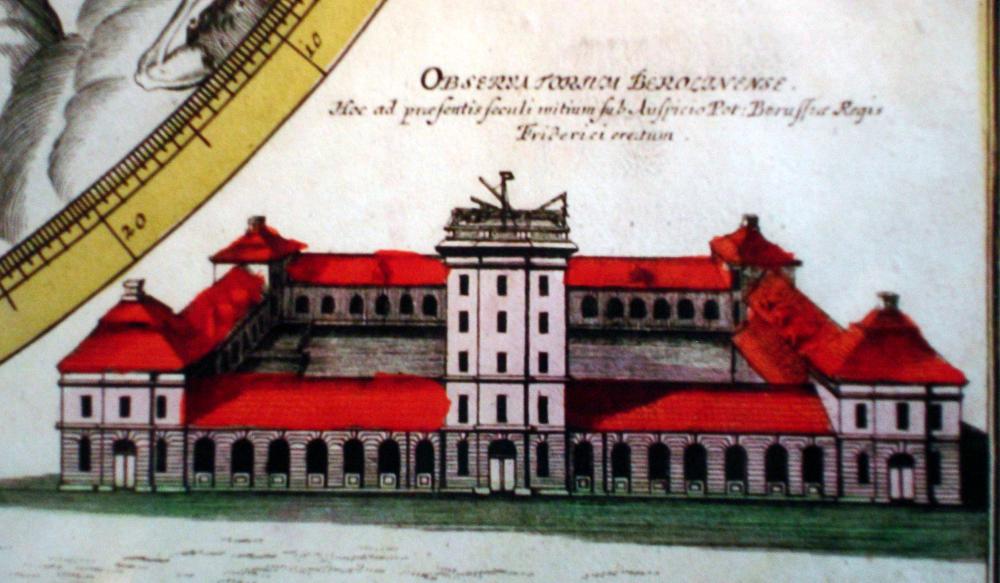

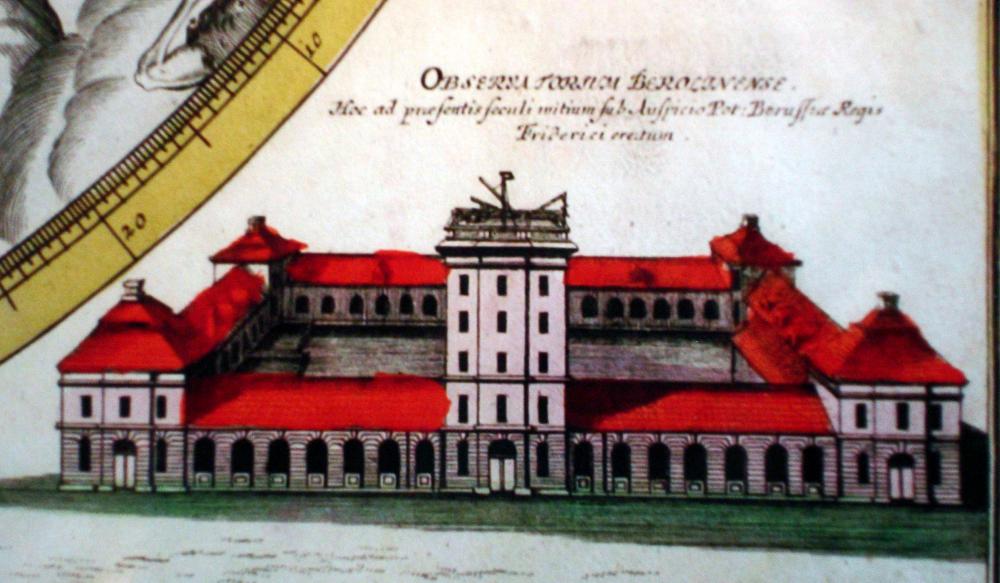

Fig. 2. The Royal Stables (Marstall) and the Academy Observatory (*1711), (Doppelmair, Johann Gabriel: Atlas coelestis. Nürnberg 1742)

As an extension of the Royal Stables to the double size, the Academy Observatory was built from 1696 to 1700 by the architect Martin Grünberg (1655--1706/07), successor of Nering.

This ("old Berlin Observatory") or Academy Observatory, was initiated by Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz (1646--1716) in 1700 when he initiated the "Kurfürstlich Brandenburgische Sozietät der Wissenschaften" (Electoral Brandenburg Society of Sciences), which would become in 1701 the Royal Prussian Society of Sciences, and in 1744 the Royal Academy of Sciences. Under Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767--1835) it was renamed Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences (Königlich-Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin), since 1992 Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Friedrich III. (1657--1713), Elector of Brandenburg, 1688 to 1713, officially founded the Academy on July 11, 1700 and appointed its initiator Leibniz as the first president. Friedrich III. became as Friedrich I. the first King in Prussia from 1701 to 1713. The Electoral Brandenburg Society of Sciences (Academy of Sciences) was divided into four classes: 1. physics, medicine, chemistry, 2. mathematics, astronomy, mechanics, 3. development of the German language, 4. literature.

Fig. 3. Marstall Academy Observatory (*1711), Dorotheenstr. 27 (Baedecker Berlin 1877)

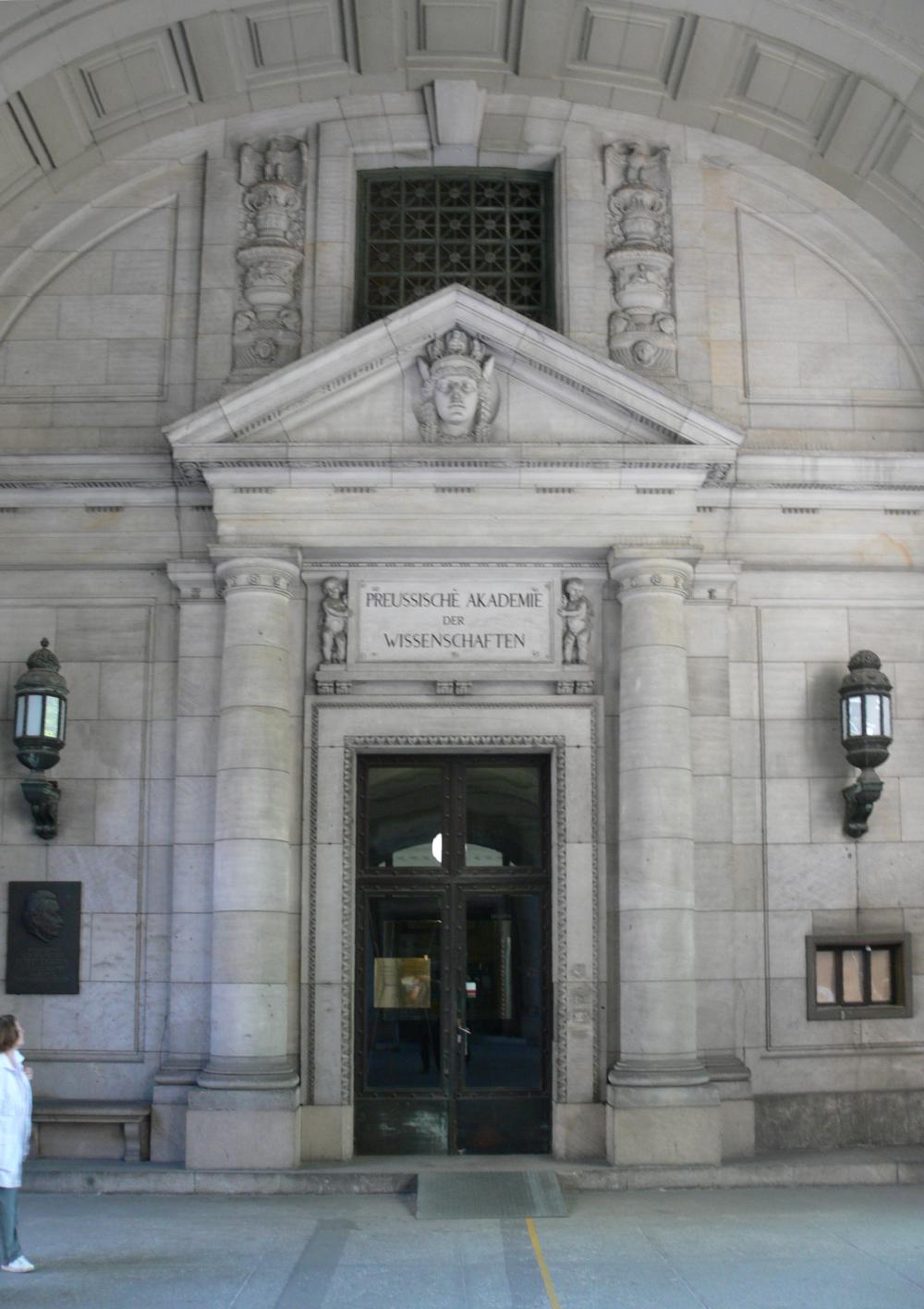

After the demolition, Ernst Eberhard von Ihne (1848--1917) built a new complex in the square Unter den Linden, Charlotten-, Dorotheen-, Universitätsstraße (1903--1914). This new building exists until today as State and University Library with the Library of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences.

The First Astronomers

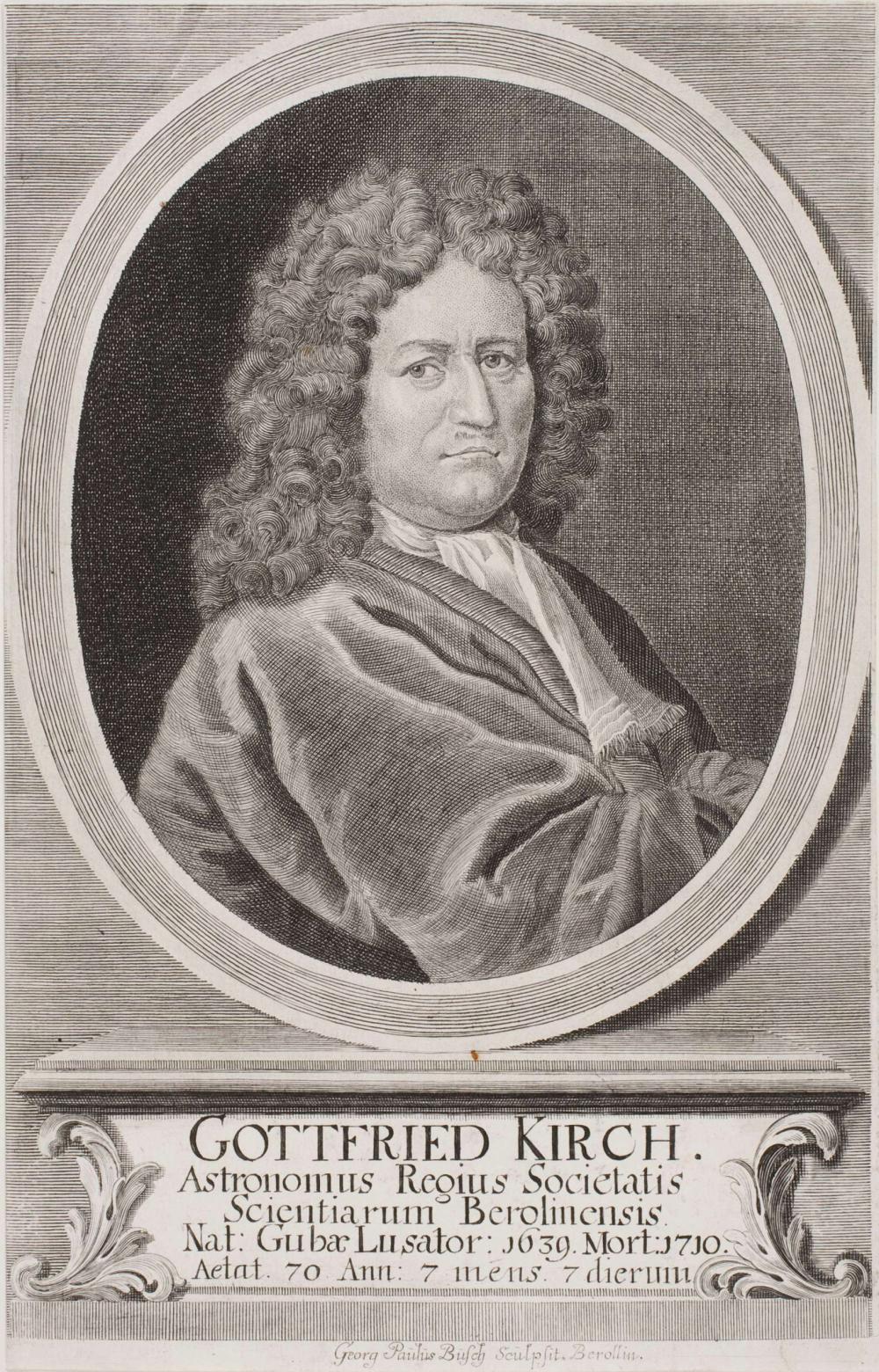

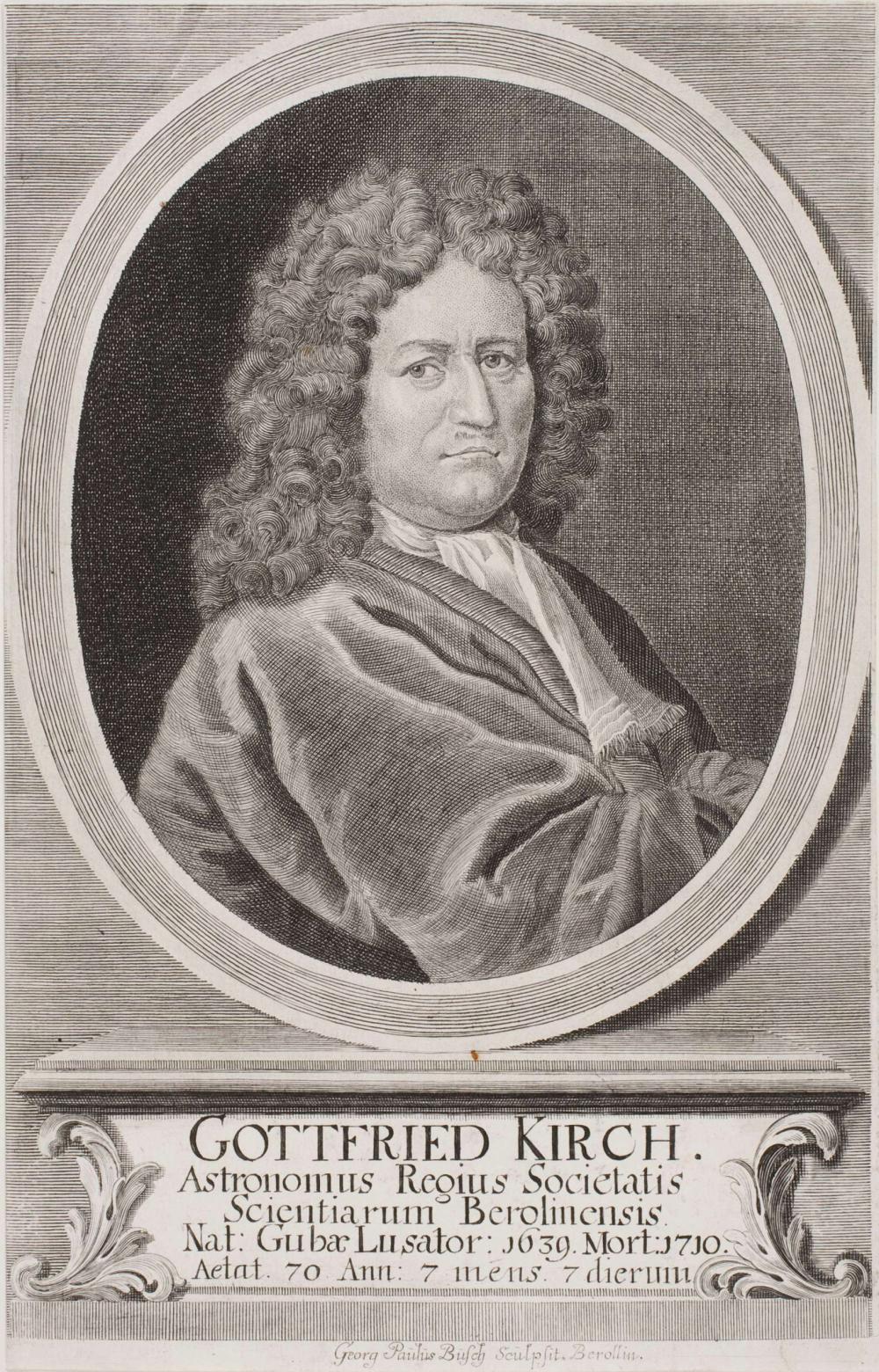

Fig. 4a. Gottfried Kirch (1639--1710), (Georg Paul Busch, CC)

Fig. 4b. Maria Margaretha Kirch-Winkelmann (1670--1720), (CC4, Alzinous)

The famous astronomer and director of the observatory was Gottfried Kirch (1639--1710), the first ’Astronomer Royal’ in Berlin from 1700 to 1710. He had studied at the University of Jena, and had received training in astronomy by Johannes Hevelius. In 1680, he discovered a comet - Comet C/1680 V1 - the first by using a telescope. In 1681, he discovered the open star cluster M 11. In 1786, he found the Mira variable ¤ç Cygni. He also devoted a lot of time for observing the variable star Mira (Wunderstern am Hals des Walfisches. Leipzig 1678). His main task was creating Almanacs and Calendars, already before he became director in Berlin. The Almanacs helped to distribute the ideas of the Enlightenment and Pietism to the public.

The first observations in the observatory tower could be made in 1706 with moveable instruments and a clock (Stutzuhr). The astronomer lived in Dorotheenstrasse 10. Gottfried Kirch died one year before the observatory was ready (1711).

Kirch’s second wife Maria Margaretha Kirch-Winkelmann (1670--1720), married in 1692, was also active as an astronomer. Maria Margaretha worked in the household of the farmer and astronomer Christoph Arnold (1650--1695) in the village of Sommerfeld, where she acquired basic knowledge and experience in the field of astronomical observations and meteorology, later she was further trained by Gottfried Kirch. Maria Margaretha Kirch-Winkelmann assisted in observations and to run calculations. While observing the comet of 1702 together, he discovered the globular cluster M 5.

Other female astronomers of the 17th century were Maria Cunitz, Elisabeth Hevelius, and Maria Clara Eimmart.

Maria Margaretha Kirch-Winkelmann is considered the first woman to discover a comet (Comet C/1702 H1):

"Early in the morning (about 2:00 AM) the sky was clear and starry. Some nights before, I had observed a variable star and my wife (as I slept) wanted to find and see it for herself. In so doing, she found a comet in the sky. At which time she woke me, and I found that it was indeed a comet ... I was surprised that I had not seen it the night before."

(Notebooks of Gottfried Kirch, quoted after Helly & Reverby 1992)

She also made observations of the variable star Mira Ceti.

Fig. 5a. Signature of Leibniz

In 1709, Gottfried von Leibniz presented her to the Prussian court, where Maria Margaretha Kirch explained her observations of sunspots:

"There is a most learned woman who could pass as a rarity. Her achievement is not in literature or rhetoric but in the most profound doctrines of astronomy ... I do not believe that this woman easily finds her equal in the science in which she excels... She favors the Copernican system (the idea that the Sun is at rest) like all the learned astronomers of our time. And it is a pleasure to hear her defend that system through the Holy Scripture in which she is also very learned. She observes with the best observers and knows how to handle marvelously the quadrant and the telescope." (quoted after Helly & Reverby 1992)

Fig. 5b. Krosigk Private Observatory (*1706), (copperplate by Georg Paul Busch, 1710)

After the death of her husband, she was not accepted by the academy and was not paid for her continuing work, inspite of the fact that the new director Johann Heinrich Hoffmann (1669--1716) was not really able to do successful work. Finally in 1712, Kirch gave up and accepted the patronage of the amateur astronomer Baron Bernhard Friedrich von Krosigk (1656--1714), who had since 1706 a private observatory in Wallstrasse 72, Neu-Cölln. After the death of Krosigk, Kirch moved to Danzig from 1714 to 1716. Then she calculated calendars in her home in Berlin for Nuremberg, Dresden, Breslau (Wroclaw), and Hungary.

Maria Margaretha had also trained her son and her daughters, especially Christine Kirch (1697--1782) and Margaretha Kirch (~1703-- after 1744), who became active in astronomy. Her son Christfried Kirch (1694--1740) was called as director from 1716 to 1740.

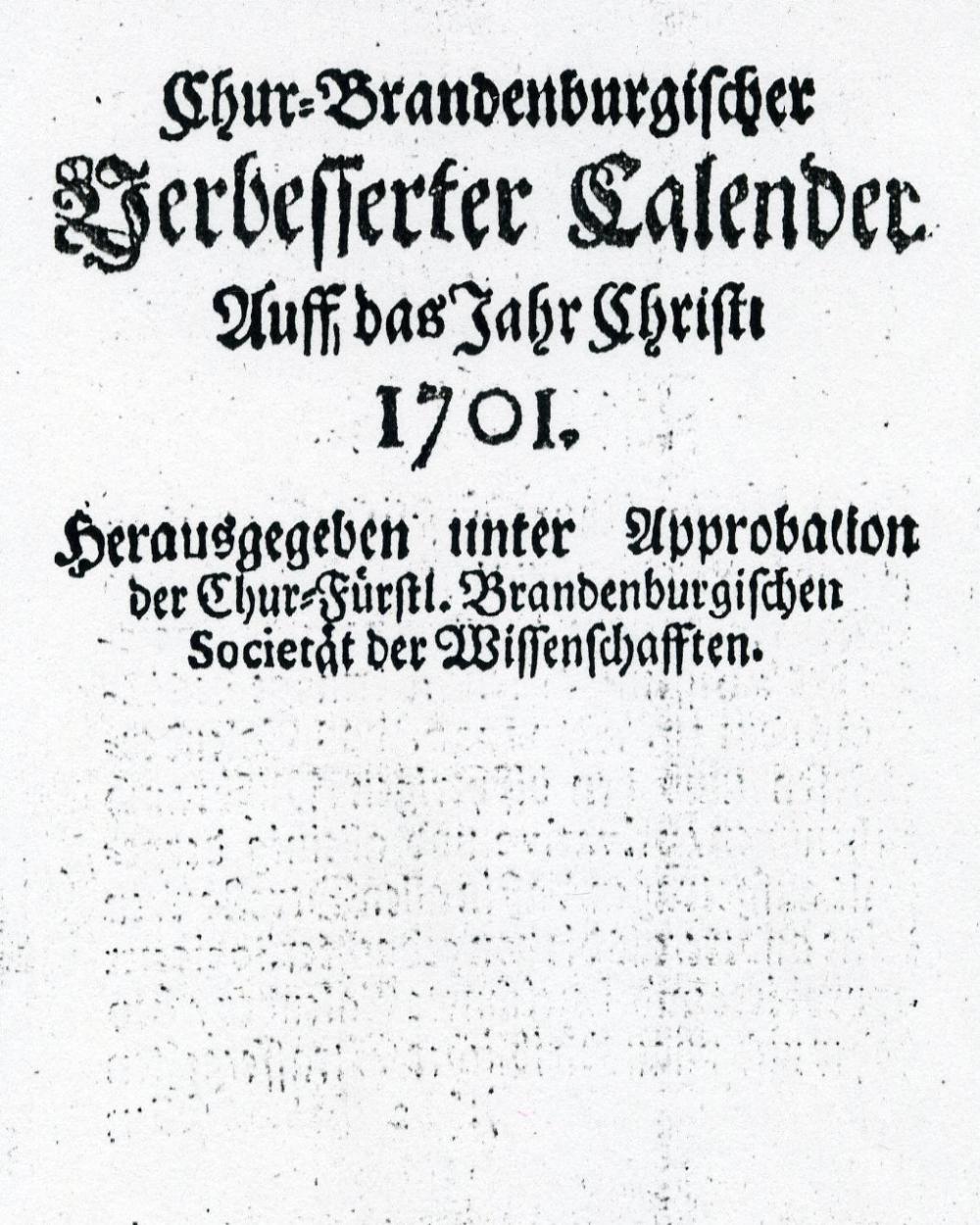

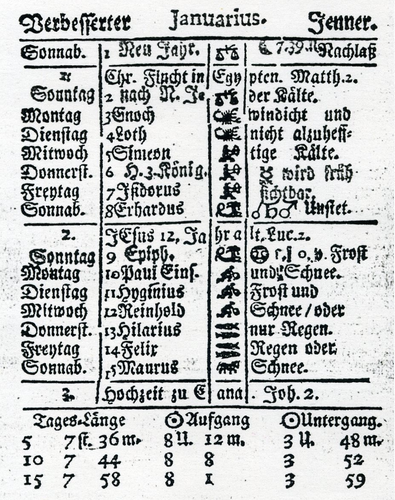

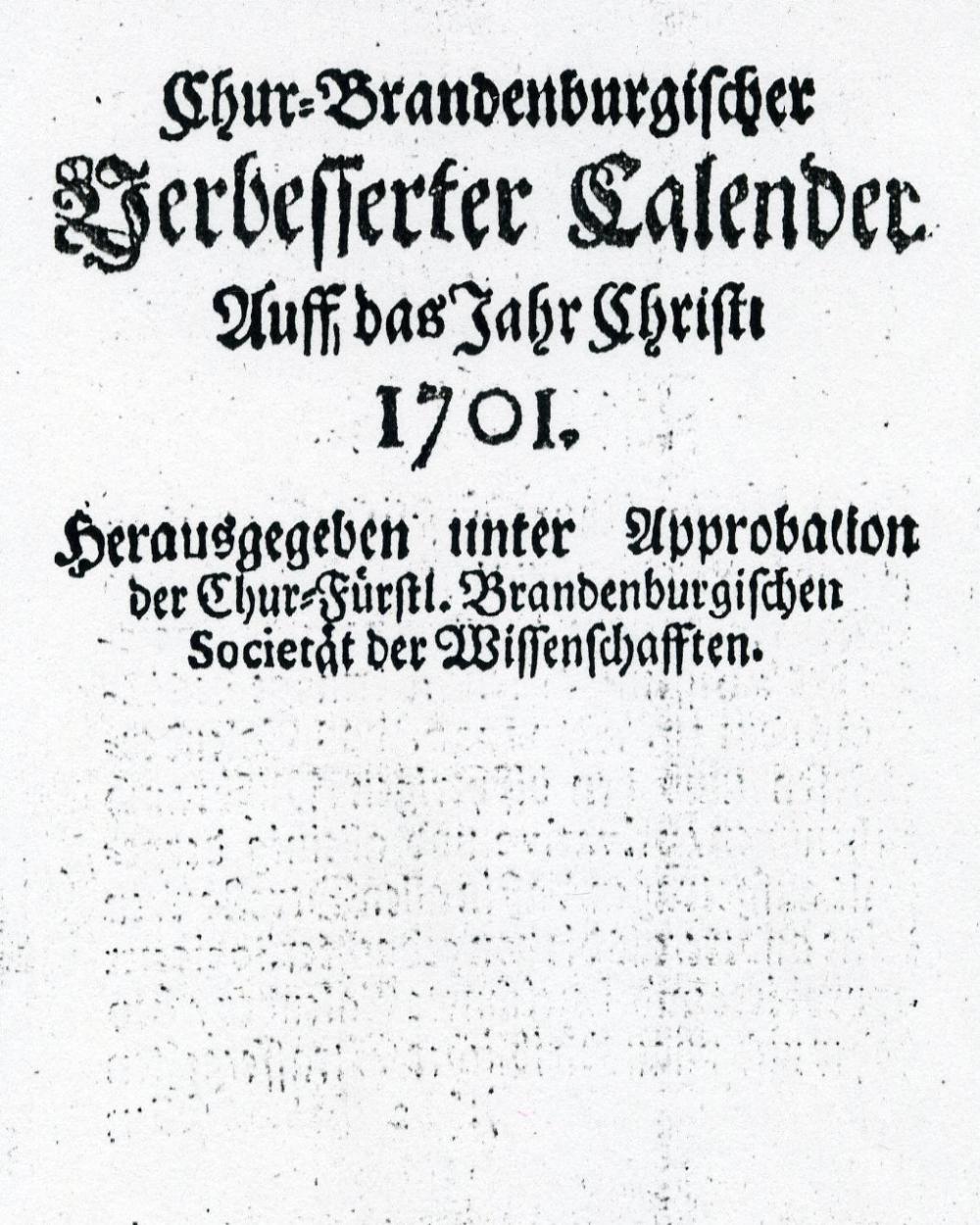

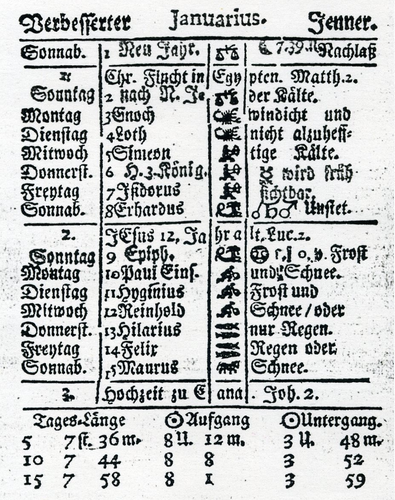

Fig. 6a. Chur-Brandenburgischer Verbesserter Calender Auff das Jahr Christi 1701 (Astronomisches Recheninstitut ARI, kal1701s1)

Fig. 6b. Chur-Brandenburgischer Verbesserter Calender Auff das Jahr Christi 1701

The Calendar Privilege and the Protestant Calendar Reform

As an income for the observatory and the salary of the director, Friedrich III introduced through an edict a monopoly for calendars in Brandenburg, and later Prussia, imposing a calendar tax. The basic idea came from Erhard Weigel (1625--1699), professor of mathematics at the University of Jena, who had proposed a similar calendar privilege for a Germany-wide Academy. The academy’s calendar privilege expired in 1811 in the course of Wilhelm von Humboldt’s reforms.

The Academy of Sciences in Berlin handled sales of their calendars.

The introduction of an "Improved Calendar" (Gregorian Calendar)

The Protestants did not grant the Pope the right to reform the calendar and initially retained the old "Julian calendar". It was not until September 23, 1699 (Julian, October 3 Gregorian) that the Protestant Imperial Estates decided at the Perpetual Diet of Regensburg to introduce an "Improved Calendar" from 1700 onwards. They practically adopted the Gregorian Calendar to count the days and therefore omitted 11 days (February 19 to 29, 1700).

However, Easter (on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the beginning of spring) should be determined in an astronomically correct way (and not approximately according to the Easter algorithm). This is the reason for the founding of the Academy Observatory with an astronomer for calculating the calendar.

In 1768, the Academy Observatory received a mural quadrant made by John Bird of London; this was the first really important observing instrument, which is preserved in Babelsberg Observatory.

The Academy Observatory was used until the New Observatory or "Königliche Sternwarte zu Berlin" (Royal Observatory Berlin) was built in 1835 as University Observatory.

History

The Berliner Astronomisches Jahrbuch (for 1776), already published in Berlin 1774, initiating the longest-lasting publication series in astronomy -- until 1959.

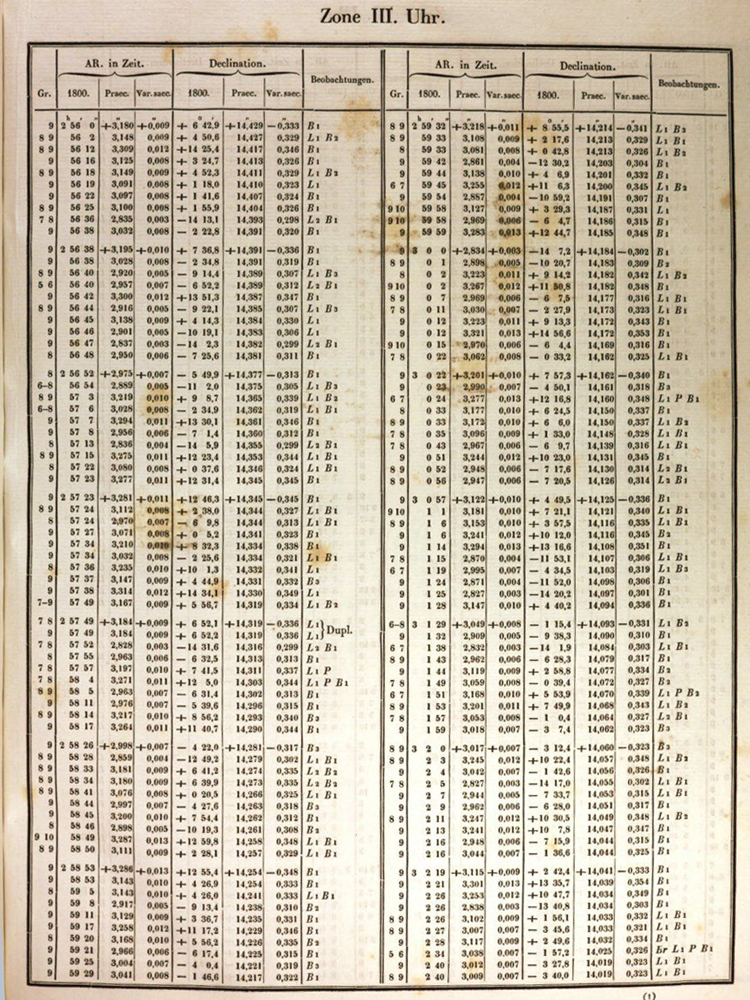

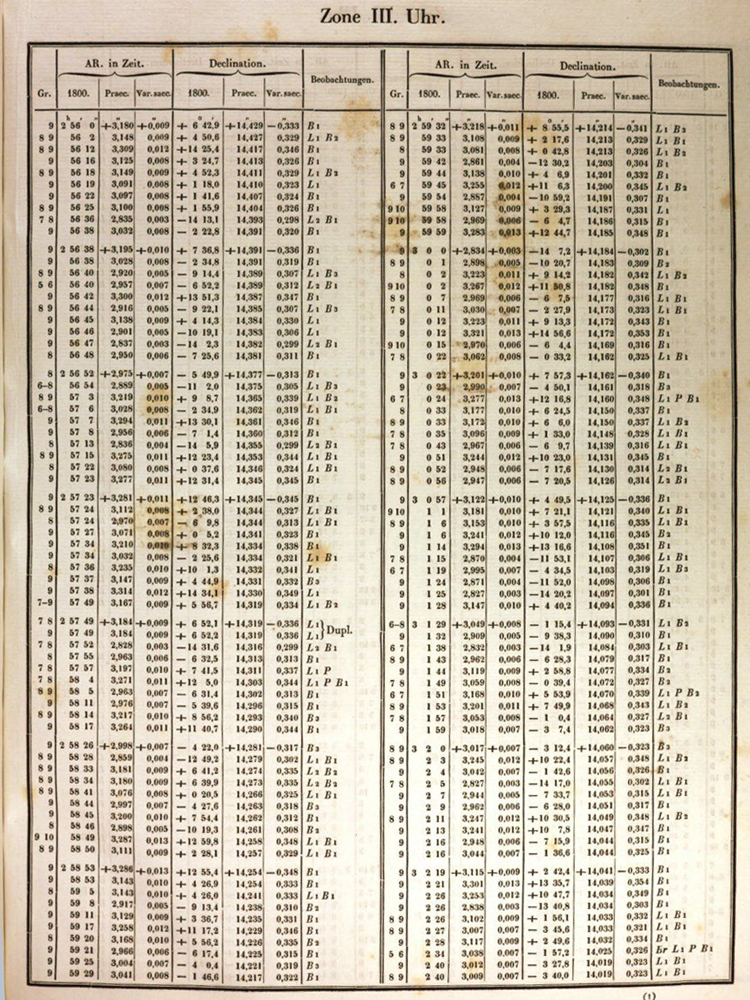

Fig. 7. Akademische Sternkarten (Academic Star Charts) Berlin 1830--1858

Akademische Sternkarten - Academic Star Charts

The so-called Akademische Sternkarten (Academic Star Charts) cover Zone Hora 0 - Hora XXIII, Blatt 1-24 for the epoch 1800. They were observed since 1830 by many observers in different countries (see list), engraved by Auguste Kolbe:

Verzeichniss der von Bradley, Piazzi, Lalande und Bessel beobachteten Sterne in dem Theile des Himmels zwischen 2h56’ bis 4h04’ gerader Aufsteigung, und 15° südlicher bis 15° nördlicher Abweichung, berechnet und auf 1800 reducirt. Berlin: Gedruckt in der Druckerei der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften, in Commission in F. Dümmler’s Verlags-Buchhandlung, 1830--1858. (Wolfschmidt 2022).

International collaboration between leading astronomers aimed to find the missing planet between Mars and Jupiter (Wolfschmidt 2020). To realize this, the sky had to be divided into 12 zones. Every two members were assigned one of the 12 zodiac constellations for the search; they had to create an exact map with stars up to 9th magnitude. After the well-known discovery of the first four planetoids Ceres (Piazzi 1801), Pallas (Olbers 1802), Juno (Harding 1804), and Vesta (Olbers 1807), the acticity with the compilation of the star maps made no considerable progress. However, since the astronomers expected further discoveries of planetoids, Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (1784--1846) made an important proposal to the Berlin Academy of Sciences in 1824, to offer a bonus for each completed map. After 35 years, Johann Franz Encke (1791--1865) was finally able to present the complete Berlin Academic Star Charts to the Academy in 1858.

Fig. 8a. Marstall Academy Observatory (*1711), Station 1 of the Prussian Optical Telegraph (1832--1848), (CC3, watercolor painting by Leopold Ludwig Müller, 1824)

Fig. 8b. Tower of the old Berlin Academy Observatory (*1711) with signal mast of Station 1 of the Prussian Optical Telegraph, used between 1832 and 1848, view from the West (credit: F. W. Klose)

Station 1 of the Prussian Optical Telegraph, used between 1832 and 1848

The Marstall (Royal Stables), Unter den Linden and Dorotheenstrasse, had been erected from 1687 to 1688 according to the plans of the architect Johann Arnold Nering. From 1696 to 1700, Martin Grünberg extended the complex northwards (Dorotheenstrasse) for the new Societät der Wissenschaften.

From 1700 until 1711, the observatory, a 27-meter-high tower of three storeys, built by Grünberg, was added to the northern wing as observatory with a platform for the long telescopes.

This first Berlin observatory, the Marstall, the Academy Observatory was a tower observatory like several in the 18th century.

The New Royal Observatory in Berlin was built in 1835.

Directors in the Academy Observatory (1700 to 1835)

- 1700 to 1710 -- Gottfried Kirch (1639--1710)

- 1710 to 1716 -- Johann Heinrich Hoffmann (1669--1716)

- 1716 to 1740 -- Christfried Kirch (1694--1740)

- 1740 to 1745 -- Johann Wilhelm Wagner (1681--1745)

- 1745 to 1749 -- Augustin Nathanael Grischow (1726--1760)

- 1752 -- Joseph Jérôme Le Francais de Lalande (1732--1807)

- 1754 -- Johann Kies (1713--1781)

- 1755 -- Franz Ulrich Theodosius Aepinus (1724--1802)

- 1756 to 1758 -- Johann Jakob Huber (1733--1798)

- 1758 -- Johann Albert Euler (1734--1800)

- 1764 to 1787 -- Johann III Bernoulli (1744--1807)

- 1787 to 1825 -- Johann Elert Bode (1747--1826)

- 1825 to 1863 -- Johann Franz Encke (1791--1865)

State of preservation

The Academy Observatory is no longer existing. The large mural quadrant, made by John Bird of London (1768), is preserved in Babelsberg Observatory in Potsdam.

Comparison with related/similar sites

Fig. 9. The Royal Stables (Marstall) and the Academy Observatory (*1711), (Doppelmair, Johann Gabriel: Atlas coelestis. Nürnberg 1742)

This first Berlin observatory, the Marstall, was a tower observatory like several in the 18th century.

Clementinum Prague (1722), Zwehrenturm in Kassel (1710), Specola - Bologna Observatory (1712), Old Vienna Academy Observatory -- tower on the top (1755), Osservatorio Astronomico di Brera of the Jesuits in Milano (1762), Padova (Padua) Observatory (1767), Mannheim Observatory (1772).

Very large tower observatories are:

Kremsmünster, Austria (1749), Mathematical Tower of the University Breslau / Wrocław (1791), Bogotá Observatory, Columbia (1803).

Threats or potential threats

No longer existing.

Present use

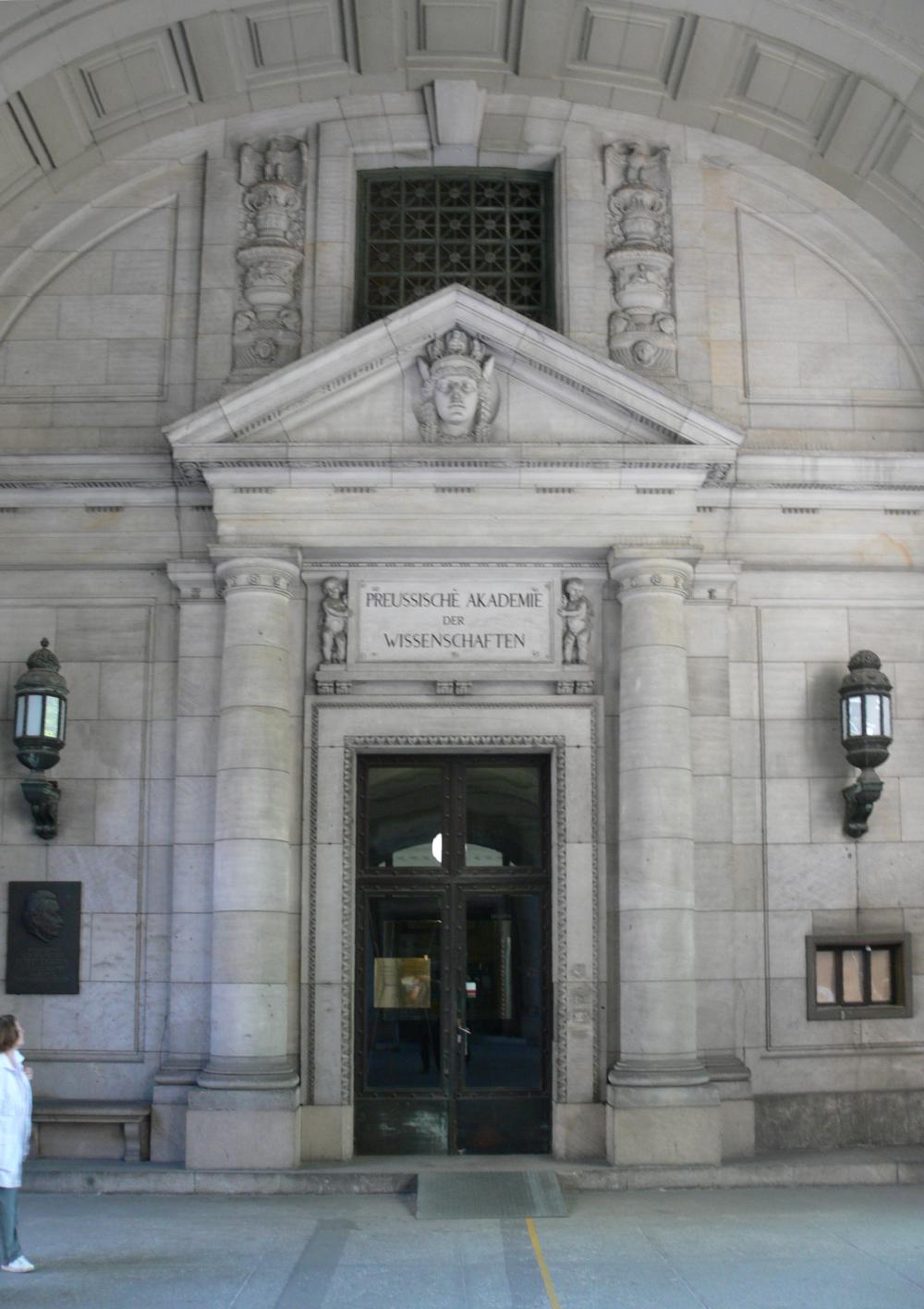

Fig. 9a. Preussische State Library and Academy of Sciences (CC3, Bundesarchiv B145, Bild P016012)

Fig. 9b. Entrance of the Prussian Academy of Sciences (CC3, Andreas Praefcke)

The Marstall Academy Observatory Berlin is no longer existing. It was demolished, and Ernst Eberhard von Ihne (1848--1917) built a new complex in the square Unter den Linden, Charlotten-, Dorotheen-, Universitätsstraße (1903--1914). This new building exists until today as State and University Library with the Library of the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences.

Astronomical relevance today

No longer existing.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles)

- Bernardi G.: Maria Margarethe Winkelmann-Kirch (1670-1720). In: The Unforgotten Sisters. New York: Springer Praxis Books 2016.

- Günther, Siegmund: Krosigk, Bernhard Friedrich Baron von. In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB), Band 17. Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot 1883, p. 196.

- Harnack, Adolf: Geschichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, im Auftrage der Akademie bearbeitet, Berlin 1900. Vier Teilbände:

Von der Gründung bis zum Tode Friedrichs des Großen, Band 1, Teil 1.

Vom Tode Friedrichs des Großen bis zur Gegenwart, Band 1, Teil 2.

Urkunden und Actenstücke zur Geschichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Band 2.

Gesammtregister über die in den Schriften der Akademie von 1700--1899 erschienenen wissenschaftlichen Abhandlungen und Festreden. Bearbeitet von Dr. Otto Köhnke. Band 3. - Helly, Dorothy O. & Susan Reverby: Gendered Domains: Rethinking Public and Private in Women’s History: Essays from the Seventh Berkshire Conference on the History of Women. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press 1992, p. 57-68.

- Herbst, Klaus-Dieter: Der Societätsgedanke bei Gottfried Kirch (1639-1710), untersucht unter Einbeziehung seiner Korrespondenz und Kalender. In: Acta Historica Astronomiae, Vol. 15 (2002), p. 115.

- Herbst, Klaus-Dieter: Die Kalender von Gottfried Kirch. In: Acta Historica Astronomiae, Vol. 23 (2004), p. 115.

- Herbst, Klaus-Dieter: Die Korrespondenz des Astronomen und Kalendermachers Gottfried Kirch (1639-1710). Briefe 1689-1709. Jena: IKS Garamond 2006.

- Herbst, Klaus-Dieter: Gottfried Kirch (1639-1710). Astronom, Kalendermacher, Pietist, Frühaufklärer. Jena: Verlag HKD 2022.

- Joos, Katrin: Gelehrsamkeit und Machtanspruch um 1700. Die Gründung der Berliner Akademie der Wissenschaften im Spannungsfeld dynastischer, städtischer und wissenschaftlicher Interessen. Köln: Böhlau 2012.

- Kirch, Gottfried: Eilfertiger kurtzer Bericht an einen guten Freund von dem Neuen Cometen dieses 1682. Jahrs. 1682.

- Neuhäuser, Ralph; Arlt, R. & S. Richter: Reconstructed sunspot positions in the Maunder Minimum based on the correspondence of Gottfried Kirch. In: Astronomische Nachrichten, Vol. 339 (2018), p. 219-267.

- Schiebinger, L.: Maria Winckelmann at the Berlin Academy: A turning point for women in science. In: Isis 78 (1987), 2, p. 174-200.

- Schmidt, Johann Marius Friedrich: Historischer Atlas von Berlin in VI Grundrissen nach gleichem Maßstabe von 1415 bis 1800. Berlin: Simon Schropp & Kamp 1688, 1835.

- Trimble, V. et al.: Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer Science & Business Media 2007, p. 639.

- Wattenberg, Diedrich: Kirch, Gottfried. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB). Band 11. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 1977.

- Wielen, Roland: "Leibniz-Objekt des Monats: Leibniz und das Kalender-Edikt von 1700". Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften (March 2016).

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Internationalität in der astronomischen Forschung vom 17. bis zum 21. Jahrhundert. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Internationalität in der astronomischen Forschung (18. bis 21. Jahrhundert). Internationality in the Astronomical Research (18th to 21st Century). Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis; Vol. 49) 2020, p. 22-115, here p. 42-50.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Carte Stellari dell’Accademia di Berlino / Berlin Academic Star Charts. In: Cosmic Pages - Atlanti stellari negli osservatori astronomicic italiani. Star Atlases in the Italian Astronomical Observatories. Ed. by Ileana Chinnici & Mauro Gargano. Paris: Arteum 2022, p. 153-157.

- Yount L.: A to Z of Women in Science and Mathematics. New York: Infobase Publishing 2007.

Links to external sites

- Berlin Observatory (Wikipedia)

- Martin Grünberg (Wikipedia)

- Gottfried Kirch (Wikipedia)

- Maria Margaretha Kirch (Wikipedia)

- Wielen, Roland: LEIBNIZ UND DAS KALENDER-EDIKT VON 1700 (März 2016)

- Hamel, Jürgen: Wissenschaftsförderung und Wissenschaftsalltag in Berlin 1700--1720 -- dargestellt anhand des Nachlasses des ersten Berliner Akademieastronomen Gottfried Kirch und seiner Familie (Leibniz-Sozietät)

- Johann Heinrich Hoffmann

- Johann Wilhelm Wagner

- McClean, Janice: In remembrance of Maria Winckelmann (2020 December 4)

- Kirch, Gottfried (Biobibliographisches Handbuch der Kalendermacher von 1550 bis 1750)

Links to external on-line pictures

no information available

No multimedia content published

Currently there is no multimedia content published for this case study