Category of Astronomical Heritage: tangible movable

Nebra Sky Disc — Bronze Age representation of the sky, Germany

Presentation and analysis

Geographical position

Place of manufacture

No information available

Place of discovery

No precise information available

Place of storage or display

The Nebra Sky Disc is on permanent exhibition at the State Museum of Prehistory (Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte) in Halle—the archaeological museum of the German state of Saxony-Anhalt.

Location

Place of manufacture

No information available

Place of discovery

No precise information available

Place of storage or display

Current location: Latitude 51° 29′ 54″ N, longitude 11° 57′ 45″ W, elevation 100m.

Physical description

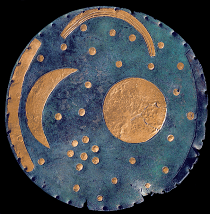

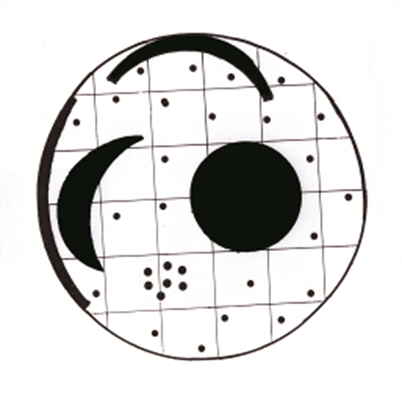

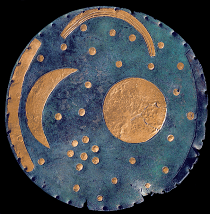

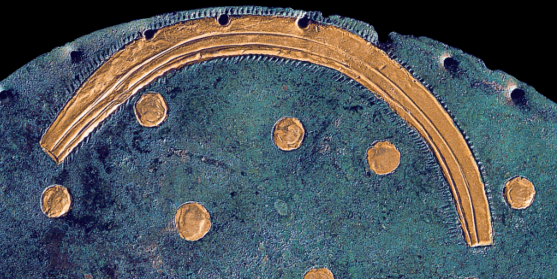

Fig. 1a. Nebra Sky Disc, front. Photo © Emília Pásztor

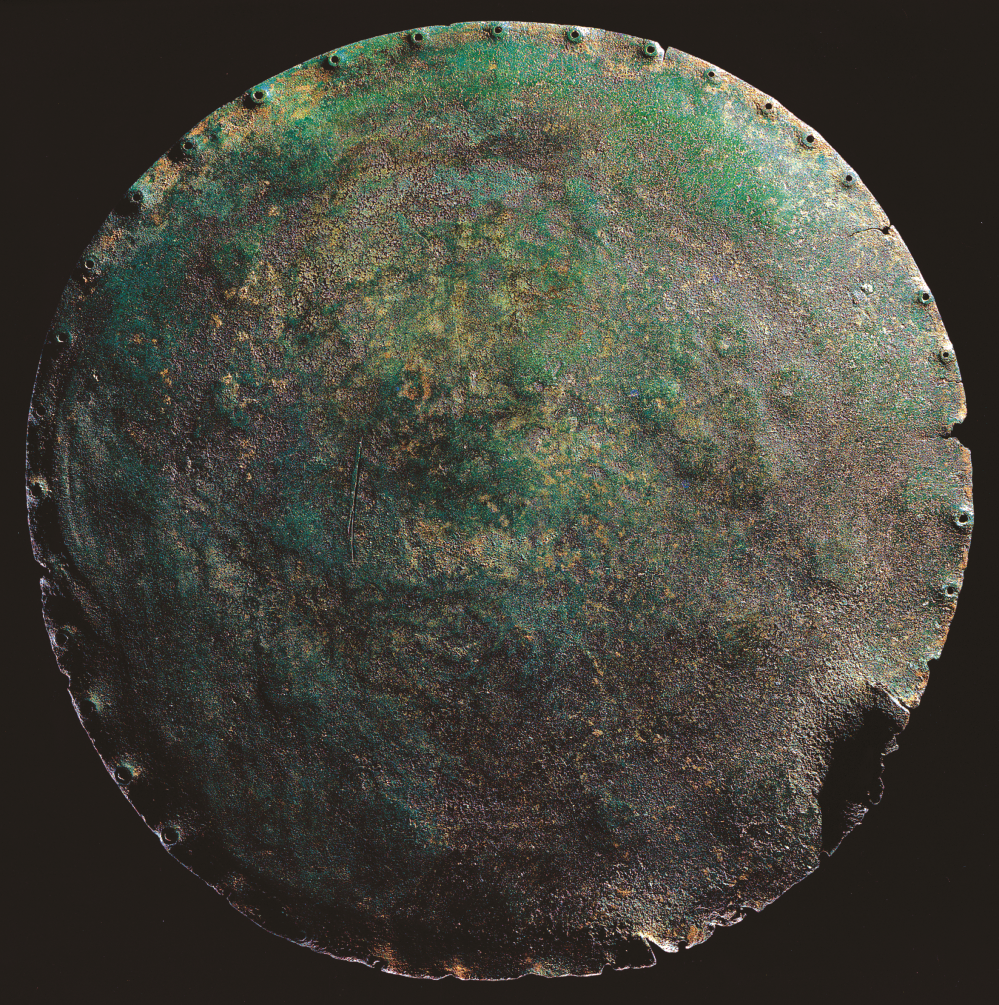

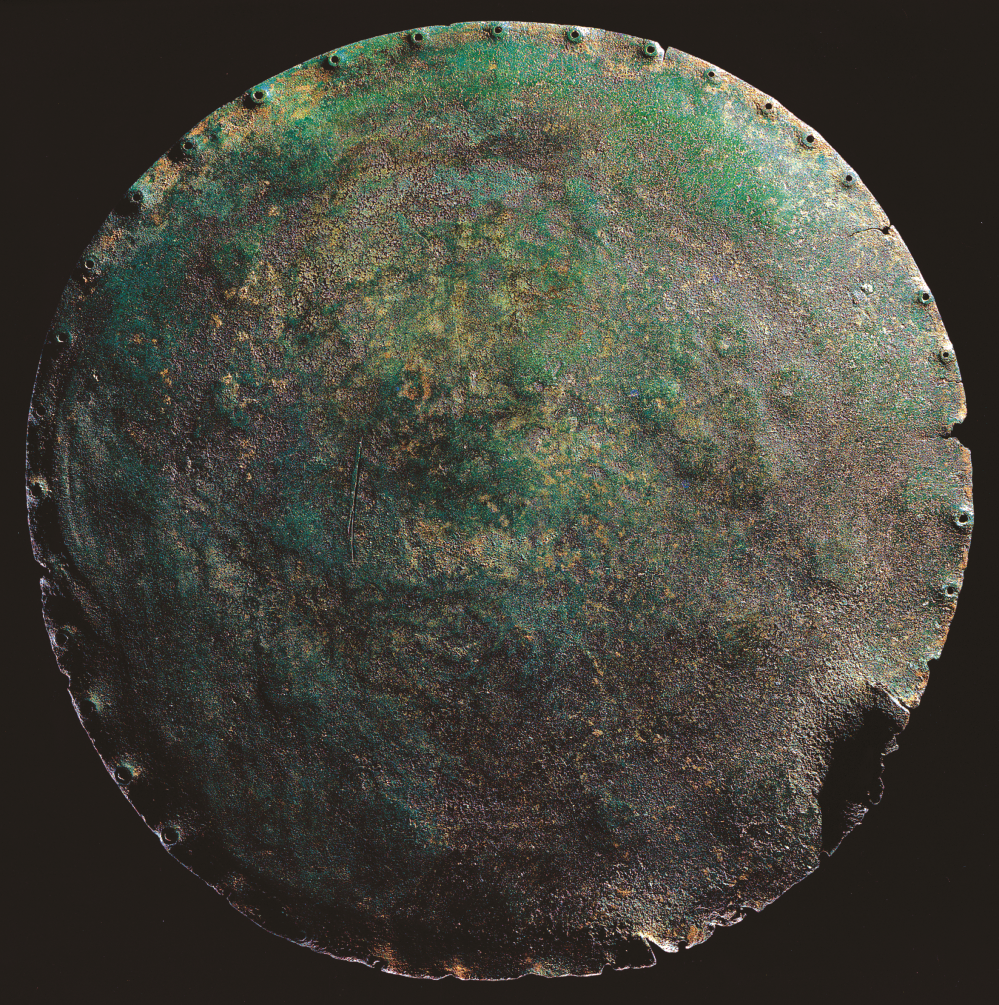

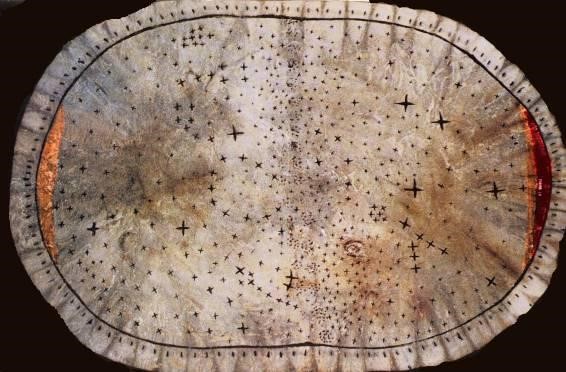

Fig. 1b. Nebra Sky Disc, back. After H. Meller, Der Geschmiedete Himmel (2004), p. 24

The bronze disc (Figure 1a-b) weighs 2kg and has a diameter of 320mm, with a thickness of 4.5mm at its centre thinning out to 1.5mm at the rim. The centre of the disc is dominated by two gold plates, each about 100mm across. One is a filled circle while the other forms a crescent (lune). The surface of the disc is further adorned with small round thin gold spots (measuring 10mm in diameter) of which there were originally 32. Two of these have been removed and one slightly adjusted to make room for two thin gold strips, curved into arcs, lining the rim of the disc. One of these arcs is now missing. A shorter curved gold strip is placed along the rim between the two long gold arcs. Each of the two thin arcs lining the rim of the disc subtends nearly 90 degrees, or a quarter of a circle, with a radius of 160mm. The shorter gold strip on the rim between them measures about 120 degrees, or a third of a full circle with a radius of 90mm. The profile of the disc is almost flat and the back of the disc shows no trace of any attachment (Figure 1b). However, the rim of the disc is punctuated by 38 (?) pin-holes which may indicate that it was sewn onto fabric or nailed onto wood.

History

The Nebra Sky Disc was found during an illegal excavation by two treasure-hunters in the summer of 1999. The Swiss police retrieved it in 2002 and returned it to Germany, where it is now on display.

The Disc has been dated to 1600 BC in the Early Bronze Age, along with two bronze swords decorated with gold pommels, two flanged bronze axes, two bronze arm-spirals and one bronze chisel that the treasure-hunters claimed to have found at the same place (Meller 2002).

Use and cultural dimension

Archaeological significance and use

The Early Bronze Age Nebra hoard comprises the Nebra Sky Disc, two bronze swords decorated with gold pommels, two flanged bronze axes, two bronze arm-spirals and one bronze chisel. Although the Sky Disc was separately offered for purchase, the treasure hunters claimed to have found the other part of the hoard at the same place. The archaeological context of the Sky Disc can be deduced from these accompanying finds in the hoard, which can all be dated to the Early Bronze Age, around 1600 BC, in central Europe—the period of the classical Ún─òtice Culture. C14 analyses of a small piece of birch bark found in the handle of one sword confirmed this date, which is the time when the hoard was buried, not the time of the production of the Disc.

Synchrotron X-ray fluorescence (SyXRF) analyses revealed that there are three types of gold on the Sky Disc which can be distinguished from each other by their Ag and Sn concentrations (Pernicka et al., 2008; Gumprich, 2004). The filled circle (‘sun’), crescent (‘moon’) and smaller spots (‘stars’) were attached first. At some time later, one star was replaced and the two horizon arcs were attached. The attachment of the shorter curved gold strip (‘rainbow’) appears to have been a separate, final step.

The chemical composition of gold in the sun plate of the Nebra Sky Disc correlates closely with natural gold from the River Carnon in Cornwall, England (Ehser et al. 2011, 908). This minor gold deposit is found in association with alluvial tin deposits that were important in prehistoric times. On the other hand, metallurgical investigations of the possible source of the copper used in making the bronze for the Disc still indicates the Mitterberg mining district in the eastern Alps (Ehser et al. 2011, 908; Lutz et al. 2009), and this applies to all objects of the hoard as the copper used in their alloy came from the same deposit of ore.

The source of the gold in the rainbow stripe has not yet been identified.

The holes around the perimeter suggest that the Disc was attached to a support of some kind, but at 2kg it is perhaps too heavy to have been worn. It could, however, have been nailed to a shield or standard made of wood. In song XVIII, lines 478–89 of the Iliad, Homer describes in detail how Hephaestus makes a shield for the great hero Achilles:

“First fashioned he a shield, great and sturdy, adorning it cunningly in every part, and round about it set a bright rim, threefold and glittering, and therefrom made fast a silver baldric. Five were the layers of the shield itself; and on it he wrought many curious devices with cunning skill. Therein he wrought the earth, therein the heavens, therein the sea, and the unwearied sun, and the moon at the full, and therein all the constellations wherewith heaven is crowned — the Pleiades, and the Hyades and the mighty Orion, and the Bear, that men call also the Wain, that circleth ever in her place, and watcheth Orion, and alone hath no part in the baths of Ocean.”

At first sight it seems that Achilles’ shield and the Nebra Disc have several traits in common. It was not unusual in the Bronze Age to attach solar amulets to armour, or to decorate shields with symbols that might have been believed to be protective or endowed with supernatural power. From the second half of the Bronze Age, the round shields of central and northern Europe are often decorated with concentric circles, solar or star images with ray patterns, or wheel-cross signs. This was a time when warfare had become general according to the increased number of deposits of weapons (Sprockhoff 1930: Tafel 1-2; Coles 1962: Plates 28, 30, 31; Jensen 1999: 97). As the Disc was possibly found together with swords and other war items, it is conceivable that it once embellished a ceremonial shield belonging to a person of high rank, the representative of a mythical hero or the image of a god in a ritual combat.

However, there is no trace of cuts on the surface of the Disc that would suggest it had been used in combat. There is only one break on the edge of the Disc and this does not seem to have come from a sharp object. Furthermore, early shields were made of thick, hardened leather and formed over a wooden backer. No ancient shields discovered up to now have a series of holes along the edge for fastening to a base.

It seems, rather, that the Sky Disc was fixed to a standard used in a communal ceremony—presumably as the symbol of their cosmos.

As many hoards containing swords are assumed to be offered to the gods in gratitude for victory after a battle (Kristiansen 2002: 329-30), the Disc, like the armour found with it, might have been offered for this purpose.

Astronomical significance and use

Almost immediately after the Nebra Disc had been returned to Germany, it was suggested that the round gold plates embellishing the green corroded bronze disc represented stars, the sun and the moon (Meller 2002; Schlosser 2002). If this interpretation is correct, it would place the Disc among the most important finds from Bronze Age Europe, making a close investigation of the basis for an astronomical explanation imperative. Intuitively, one identifies the full circle in the centre of the Disc with the sun or the full moon and the semicircular form with the lunar crescent of the new moon or old moon.

If the larger central objects represent the sun and the moon, they are not astronomically correct. Although both the sun and the moon can be seen at the same time in the daytime sky, the convex, illuminated, part of the moon is always turned towards the sun and not away from it as on the Disc, where the sun faces the concave side of the moon. The scene might be suggestive of an eclipse, but this is highly unlikely since there is not the slightest hint in the archaeological record that Bronze Age people understood the underlying cause for an eclipse of the sun or the moon.

The small round gold spots on the Disc have generally been thought of as stars, and one cluster of seven spots lying between the ‘sun’ and the ‘moon’ has naturally been associated with the Pleiades (Schlosser 2002; 2003).

Some 3600 years ago, the Pleiades lay close to the vernal equinox, a point in the sky where the sun crosses the celestial equator from the southern to the northern hemisphere. This means the star group was just opposite the sun in autumn: when the sun rose they set and when the sun set they rose. During the Bronze Age that would have made the Pleiades a prominent astronomical object in the autumnal night sky—so prominent that nobody could have missed it. The dashed line in Figure 3 marks the celestial equator with the vernal equinox for the year 1600 BC set out as an open circle.

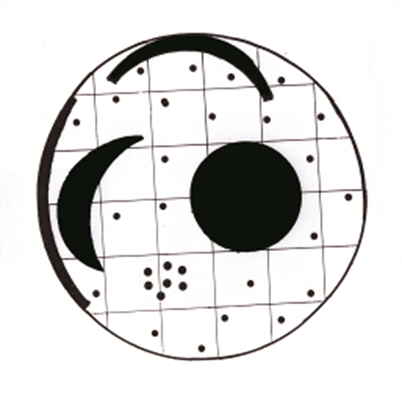

Fig. 2. Spacing of the spots on the Nebra Sky Disc. Drawing by Emília Pásztor

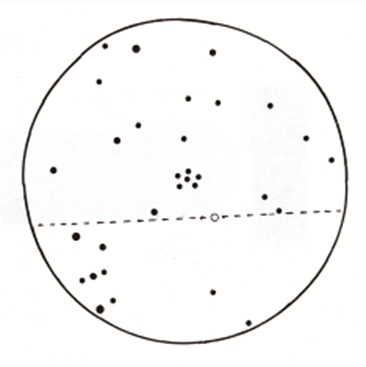

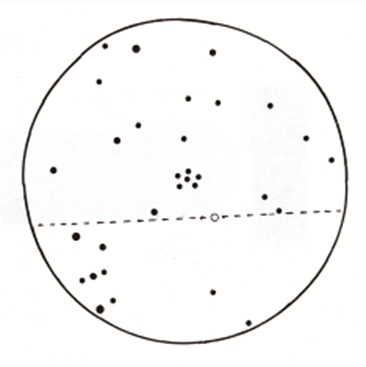

Fig. 3. Spacing of actual stars surrounding the Pleiades. Drawing by Emília Pásztor

However, the other spots are spaced too regularly on the Disc to represent the stars of the night sky (Schlosser 2004: 44). Figure 2 shows that the spots, with the exception of the ‘Pleiades’, are evenly spaced with respect to a grid (in this case of 51mm). Such regular spacing implies that they were pinned on freehand to make an aesthetically pleasing picture. Figure 3 shows the position of the same number of real stars centred on the Pleiades, all brighter than visual magnitude 3.0, which is usually the brightness limit used for delineating constellations. The stellar chart shows the uneven distribution of real stars in the sky (Pásztor and Roslund 2007). If the goldsmith intended to produce an accurate chart of the region around the Pleiades, he would hardly have omitted the conspicuous Orion constellation to the bottom left and perhaps the square of Pegasus to the right. Yuri Berezkin, a Russian historian, argues by analysing folk interpretations of the night sky that the Pleiades, Orion (mostly just the three stars in its belt and almost never containing all the stars that form the well-known Classic Greek constellation) and the seven stars of Ursa Major occupied a privileged position across the whole northern hemisphere (Berezkin 2012: 34).

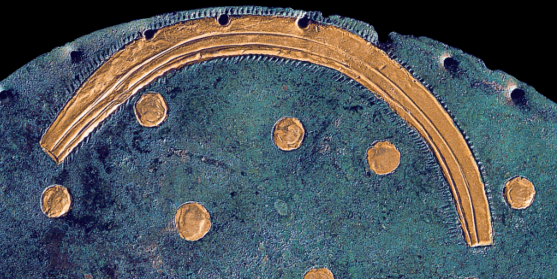

Fig. 4. The ‘rainbow’. Photo © Emília Pásztor

It has been suggested that the shorter gold curved strip at the rim of the Nebra Disc, with its three parallel incised arcs, was a depiction of a rainbow (Figure 4), showing the bands of colour (British Archaeology 2004: 16–7). A rainbow would be a natural feature of Bronze Age mythology. In the old Scandinavian belief system, it was imagined to be a burning bridge created to connect the sky and the earth. It consisted of three colours of which the middle one was made of hot iron (Davidson 1988: 171).

Fig. 5. A depiction of the mythological ‘sun boat’. Photo © Emília Pásztor

A more common explanation for this arc is that it portrays the mythical boat that brought the sun across the sky from the east to the west in daytime and back to the east through the underworld at night (Meller 2004) (Figure 5).

Schlosser (2003) has drawn attention to an interesting feature of the settings of the Pleiades in connection with the seasons 3600 years ago. Their heliacal setting in March (the last day in the year when they could be seen setting in the evening twilight) and cosmical setting in October (the first day in the year when they could be seen setting in the morning twilight) could have been used by the farmers to define their working year. He cited the Greek poet Hesiod’s famous poem Works and Days from around 700 BC to support his idea.

The cluster of seven gold plates on the Disc might have represented the Pleiades but the kind of close connection with farming activities that Schlosser has suggested is unproven. The Disc does not offer solid evidence for the positions of the celestial objects, which would be needed to calculate exact astronomical phenomena (Pásztor and Roslund 2007).

Schlosser (2002) has also put forward a theory that the two golden arcs framing the rim of the Disc may show how far the sunrise and the sunset move along the horizon from one solstice to the next. They each span 82–83 degrees of the rim, which exactly matches the span of the solar rising and setting arcs on the horizon for the latitude of Mittelberg, which he argues cannot have arisen by chance. His view is given some support by the unique position of Mittelberg in the landscape. From there, the sunset reaches its most northerly point (at the summer solstice) behind Brocken, the legendary 1142m-high summit of the 75 km-distant Hartz Mountain.

Schlosser goes as far as to treat the Disc as an instrument for obtaining a calendar date by measuring the sun’s azimuth at sunrise or sunset (Schlosser 2004: 44). The Disc is certainly not a practical device for such measurements. The centres of the peripheral arcs are not marked and there is no foresight for establishing a sightline to the sun. The close agreement between their arc lengths and those of the solar rising and setting arcs might indeed be a pure coincidence, as the landmarks on the horizon at the site offer simple and completely satisfactory reference points for following the position of the sun (Pásztor and Roslund 2007, Pásztor 2014).

Comparative analysis

Archaeological

As no artefact exists that is comparable to the Sky Disc, the other finds such as the swords, axes, spiral armbands and chisel are used for typological comparison. The swords show influences from south-eastern and northern European sword-manufacture. This complex tradition can be detected in other finds from Germany between 1700 and 1500 BC. The axes represent a known group—flanged axes with a shallow ledge in the centre—that is typical in the area of the Elbe and Oder at the end of the Early Bronze Age around 1600 BC. The bent-edged chisel is also of a form that is characteristic of the period around 1600 BC. The spiral armbands cannot be used for more accurate dating as they are typical arm-jewellery common throughout the long Bronze Age period.

Astronomical

If the circular object represents the sun, its style is unusually plain. On archaeological finds of the Bronze Age Ún─òtice and other contemporary cultures the sun is always richly decorated with concentric circles, and spirals and often displays radial rays (Neugebauer 1987: Abb. 51, 54; Probst 1996: 101, 210, Figures 24-5; Kaul 2004: 56-7; Kovács 1991; Schwarz 2004: 179). Some of the symbols on archaeological finds believed to be the sun might actually have been of the full moon; this could be the case for the Nebra Disc as well. Unfortunately, portrayals of the lunar crescent like the one on the Disc seems to be rather rare: only a single example is known on a golden bowl, and this is from the later Bronze Age (Green 1993: Figure 438). On the other hand, jewellery in the unique shape of a crescent (lunulae) was produced during this period or close to it. The most prominent arm-rings ending with lunulae were produced from Transylvanian gold (Kovács 1999: Figures 26–7).

Bright stars have a distinctive radiating ray pattern (Navarro and Losada 1997), which may feature on symbols for stars from the first part of the Bronze Age, although these are difficult to distinguish from symbols for the sun (Koós 1988: 1. kep; Kovacs 1991: Abb. 2, Abb. 5; Probst 1996: 148, 197, 221). However, the plain style of the round gold plates on the Nebra Disc (both the large one and the small spots) recalls cup-marks and circles on the rock carvings of the Nordic Bronze Age. Plain circles and cup marks predominate at rock–carving sites in Denmark, although they decline in numbers when one goes further north (Malmer 1981: 68–9, 75). Depicting the stars as round objects might therefore have been intentional. In ethnographic reports on the cosmological beliefs of people in the northern part of Asia and North America, the stars are imagined as holes in the sky (MacDonald 2000: 33; Holberg 1927, 336). The Pleiades were also called Szitáslyuk or ‘The holes in a sieve’ in old Hungarian, which is supposed to be of ancient Finno-Ugric origin (Zsigmond 1999: 48).

Fig. 6. The golden arc of light on the horizon after sunset. Photo © Jari Luomanen

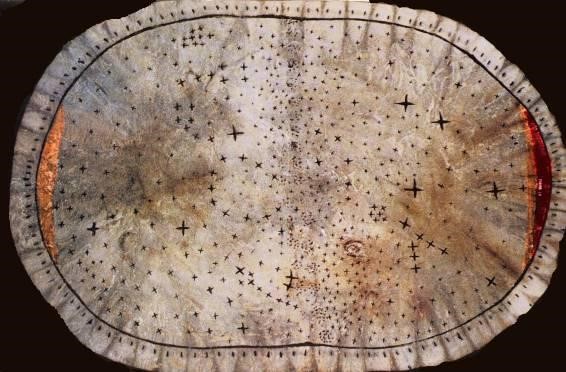

Fig. 7. Skidi Pawnee star chart. Photo courtesy of Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago

The two gold peripheral arcs on the Disc (one of which is missing) might represent the part of the celestial firmament that was always separate in ancient cosmologies. In some folk beliefs, the firmament was perceived as being made of pure gold which could be seen when the sky was lit up by lightning (Erdész 1961: 330). Alternatively, the two arcs on the Disc may symbolize two celestial phenomena that were also believed to be separate objects in the sky, namely the arcs of the golden sunset and the blush of dawn at the two opposite eastern and western horizons (Figure 6). The Skidi Pawnee Indians of North America possessed a star chart which was supposedly 300 years old. It depicts their important constellations, stars, the moon and the sunrise and sunset as the essential elements of their cosmos (Chamberlain 1982: 191, Fig. 47) (Figure 7).

The sun boat myth is well-known from ancient Egypt but it could just as well have been created in Scandinavia, where seafaring was an everyday activity in the Bronze Age. Numerous ships rendered on rock carvings support this concept. It would likewise have been natural for the sun to travel by boat as depicted clearly on rock carvings and razors from the Bronze Age (Kaul 1998). However, these boats are flat-bottomed with rising bows and sterns.

The separate arc symbolizing the ‘sun barque’—as claimed by German and Danish scholars—cannot depict a boat because it is too circular. The surface of this curved sheet of gold is also divided into three parallel bands. These probably symbolize the three colours of the rainbow, which plays an important role in later northern myths. The tiny lines that surround the arc (Figure 4) make no sense in the boat interpretation, as they run both above and under it, but they may well symbolize the brightness of the rainbow. Also, there is no known depiction of the ‘sun barque’ unaccompanied by the symbol of the sun (Pasztor and Roslund 2007; Pasztor 2014) (cf. Figure 5).

No boat with a semi-circular profile has yet been seen depicted in prehistoric Europe. In any case, in landlocked central Europe, the boat can never have been as important for transportation as in Scandinavia. This is attested by the almost total absence of boats on rock carvings in inland Europe from this period. No ships have been found on rock carvings so far in north Germany (Malmer 1981: 18). In Val Camonica, only five ships have so far been reported on rock carvings (Kaul 2005: 56). In contrast, there are frequent finds of models of wagons with sun symbols and wheels. It would have been completely natural if here the sun was believed to travel on a wagon across the sky instead of on a ship. There are even ‘sun-chariot’ finds from Scandinavia (Larsson 1996, 45, Figures 12, 14; Kaul 2004). This shows the complexity of the role the sun might have played in the Bronze Age mythology. From 1500 BC onwards, the custom of placing miniature wheels representing the sun as ornaments in graves can also be observed in Europe (Green 1993: 301–3).

A strong connection is supposed to have existed between the Nebra people and the contemporary or earlier people of western Asia, with both of them using celestial symbols that might have included the Pleiades (Meller 2004; Kristiansen and Larsson 2005). The Pleiades were recognised in Mesopotamia at the time the Nebra Disc was made. They are mentioned in a text called Prayer to the Gods of the Night from Babylon around 1830–1530 BC (Rogers 1998: 15). They are also mentioned on circular tablets (astrolabes) from about 1100 BC, which show their rising and setting points and list their implications for agriculture and mythology (Rogers 1998: 16–7). The lay-out of the closely-knit group of seven gold plates on the Disc, however, differs significantly from the depictions of the Pleiades in the Near East. There they have a more realistic elongated form (Lindsay 1972: Fig. 17; Collon 1990: Fig. 16; Black and Green 1992: 162–3, Figs. 49, 55) in sharp contrast to the round clustering on the Disc.

Kristiansen and Larsson argue that most European Bronze Age iconography can be explained by assuming that a complex pantheon of gods had spread in with the migration of proto-Indo-Europeans. Thus the worship of the Divine Twins, who were multifunctional gods from this pantheon and broke open the daylight for their sister, the sun-goddess, is indicated by references to twins in Bronze Age hoards. In northern Europe in particular, the increase in the deposition of double axes can be considered from this perspective. The Nebra hoard might have been such a sacrifice, demonstrating a close connection with the course of the sun, moon and stars. Accordingly, the Disc would have Near Eastern roots: indeed motifs of the sun, the moon and a bright star, symbols of the sky divinities, often appear on Syrian and Mesopotamian seals (Kristiansen and Larsson 2005: 264–7).

However, the Nebra Disc cannot be said to make any direct reference to this particular iconography, because on the seals the third item alongside the sun and the lunar crescent was a star, presumably Ishtar, the morning star (actually the planet Venus)—not the Pleiades. Moreover, on the cylinder seals of the third and second millennia, the crescent is almost always depicted below the sun disc and quite close to it (Collon 1990: 52, Figs. 8, 13, 17, 23, 31, 34–5, 42).

On boundary stones, the Sun and the Moon are detached from each other as on the Nebra Disc, but these royal charters are from a later period (1350–1000 BC) than the Disc. On Mycenaean gold rings (1500 BC) they are also depicted independently from each other (Goodison 1989, Figs. 129, 130) and are supposed to represent rituals that were performed on certain days of the year when they were seen simultaneously in the sky (Nagy and Valavanis 1993, Figs. 401-2). These gold rings, however, show the sun and the moon without a star. Stellar patterns could have carried local meanings for many millennia. The creation of zodiacal constellations in Mesopotamia took several millennia according to the archaeological finds and written sources. It is logical to assume that the same was true for non-Mesopotamian peoples, so one should avoid theories that suggest a single place and time of origin for the development of sky lore (Maunder 1913; Ovenden 1966; Roy 1984). From prehistoric Europe there are no written sources dealing with this process as there are in Mesopotamia or Egypt; but it seems likely that early Europeans were equally interested in the starry sky. Their sky lore can be detected in the use of celestial symbols on finds and the orientations of archaeological features such as houses, megalithic monuments and Neolithic enclosures. The investigations of these monuments have shown how important it is to survey the location and the design of monuments in relation to the surrounding landscape and the celestial bodies.

Authenticity and integrity

The authenticity of an important archaeological artefact must be established beyond all doubt, especially for a find with a somewhat obscure provenance. The Nebra Disc has therefore undergone a series of rigorous laboratory tests to prove it is genuinely ancient.

The first scientific investigations of the hoard, and particularly of the Sky Disc, concentrated on its authentication by (1) mineralogical, trace-element and lead-isotope analyses of the bronze, (2) the mineralogical and chemical composition of the corrosion layer and soil adhesions, and (3) the technology and technique of manufacture (Berger et al. 2010; Pernicka et al. 2008; Pernicka 2010).

Scientific testing methods make it possible to distinguish between modern and antique bronze:

“Bronze is an alloy of copper and tin, and the distinction in age is based on the fact that copper, like most metals, is weakly radioactive after it is smelted from the ore. The radioactivity derives from naturally radioactive lead (Pb-210) and can be identified until about 100 years after smelting. The bronze Sky Disc exhibits no measurable radioactivity and must therefore be older than this. Further indications that the object is old are the chemical composition of the metal and the structure of the corrosion layer, which is made up of large crystalline forms that need a very long time to grow.” (www.lda-lsa.de/en/nebra_sky_disc/dating).

See more details on authentication.

Management and use

Ownership

The Nebra Sky Disc is owned by the State Museum of Prehistory in Halle.

State of conservation

The Sky Disc was damaged by the treasure hunters, who partly tore off the gold plate of the sun, badly scratched the surface and struck the edge of the disc with a pick. They also cleaned it by unsuitable methods. The arc on one edge is missing, but it is possible that it was lost in ancient times.

The damage caused by the illegal excavators has now been mostly repaired: the star that came off has been put back in place and the damaged part of the large circular gold plate has been restored.

See more details on restoration.

Main threats or potential threats

There is no other threat than further corrosion but the artefact is exhibited and its condition is regularly controlled.

Protection

The artefact is safe in a protected environment in the museum.

Cultural environment

The past cultural environment for the Sky Disc is the Únětice culture, an archaeological culture at the start of the Central European Bronze Age dating roughly to 2300–1600 BC. Its range covers sites in Germany, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Austria, Poland and West Ukraine.

See more details on the Únětice culture.

Archaeological / historical / heritage research

Excavations have unearthed two parallel ramparts on the hill where the Sky Disc was found. Its location was also surrounded by a low rampart with a ditch but from a 1000-year younger period. No traces of bronze age settlement could be identified on the hill, so the place where the artefacts were deposited was likely a sacred enclosure.

As no signs of burials were found in later excavations, there is no doubt that the finds were originally deposited as a hoard covered by large stones.

Excavations on Mittelberg hill together with the statements of the treasure hunters have also managed to reconstruct the probable arrangement of the objects.

Management, interpretation and outreach

The Nebra Sky Disc is permanently exhibited at the State Museum of Saxony-Anhalt in Halle and can be seen by any visitor during opening hours.

The Disc significantly influenced and inspired archaeoastronomical research. It has greatly raised the level of interest in the ancient sky lore of illiterate societies.

At the same time, the considerable public interest has generated numerous biased, sensationalist interpretations. Added the this, the existing critiques are unfortunately ignored in many scientific articles: several researchers (such as Dathe and Krügeror 2018, Bradley and Nimura 2013, Meller 2013 and Ehser et al. 2011: 897), as well as the official webpages, still claim that the makers of the Sky Disc possessed advanced astronomical knowledge and used types of equipment that are not justified by the prehistoric social context.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles)

Berezkin, Y. 2012. Seven brother and cosmic hunt: European sky in the past. In: Universumit Uudistades Paar Sammukest XXVI. Eesti Kirjandusmuuseumi Aastaraamat 2009, 31–70. Tartu: Eesti kirjandusmuuseum.

Berger, D., Schwab, R., Wunderlich, C.-H. 2010. Technologische Untersuchungen zu bronzezeitlichen Metallziertechniken nördlich der Alpen vor dem Hintergrund des Hortfundes von Nebra. in Der Griff nach den Sternen. Wie Europas Eliten zu Macht und Reichtum kamen, F. Bertemes & H. Meller, eds., Internationales Symposium, Tagungen des Landesmuseums für Vorgeschichte Halle (Saale), Band 5/II, 751–778.

Black, J.A. & A. Green. 1992. Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia. London: British Museum Publications.

Bradley, R. & Nimura, C. 2013. The earth, the sky and the water’s edge: changing beliefs in the earlier prehistory of Northern Europe, World Archaeology, 45:1, 12–26.

British Archaeology 79, November 2004.

Chamberlain, V.D. 1982. When Stars came down to Earth. Los Altos: Ballena Press.

Coles, J. 1962. European Bronze Age shields. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 28: 156–90.

Collon, D. 1990. Near Eastern Seals. London: British Museum Publications.

Dathe, H. & Krüger, H. 2018. Morphometric findings on the Nebra Sky Disc, Time and Mind, 11:1, 89–104.

Davidson, H.R.E. 1988. Myths and symbols in pagan Europe. New York: Syracuse University Press.

Ehser, A.–Borg, G.–Pernicka, E. 2011. Provenance of the gold of the Early Bronze Age Nebra Sky Disk, central Germany: geochemical characterization of natural gold from Cornwall. European Journal of Mineralogy, 23, 895–910.

Erdész, S. 1961. The World Conception of Lajos Ami, Storyteller. Acta Ethnographica 10, 327–44.

Goodison, L. 1989. Death, women and the sun. Symbolism of regeneration in early Aegean religion. Bulletin of Institute of Classical Studies Suppl. 53.

Green, M. 1993. The sun gods of ancient Europe, in M. Singh (ed.) The sun, symbols of power and life, 295–311. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Gumprich, A. 2004. Archäometrische Untersuchungen an den Goldteilen aus dem Hortfund von Nebra. Diploma thesis, TU Bergakademie Freiberg.

Holberg, U., 1927. Finno-Ugric, Siberian. In The mythology of all races edited by C. J. A. MacCulloch, D.D., Vol. IV. Boston: Archaeological Institute of America, Marshall Jones Company

Jensen, J. 1999. The heroes: Life and Death, in Gods and heroes of Europe, 88–97. Strasbourg: Europarat.

Kaul, F. 1998. Ships on bronze. Studies in Archaeology and History 3. Copenhagen: PNM.

–2004. Der Sonnenwagen von Trundholm, in H. Meller (ed.) Der Geschmiedete Himmel, 54–7. Stuttgart: Theiss.

–2005. Bronzealderens billedverden, in F. Kaul, M. Stoltze & F.O. Nielsen (ed.) Milstreu: Helleristninger, 45–68. Rønne: Bornholms Museum.

Koós, J. 1988. Bronzezeitliches Anhängsel von Nagyrozvágy. HOMÉ 25–6: 69–80.

Kovács, T. 1991. Das bronzezeitliche Goldarmband von Dunavecse. Folia Archaeologica 42: 7–25.

–1999. Bronzezeit, in T. Kovács & P. Raczky (ed.) Prähistorische Goldschätze aus dem Ungarischen Nationalmuseum, 37–63. Budapest.

Kristiansen, K. 2002. The tale of the sword – swords and swordfighters in Bronze Age Europe. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 21: 319–32.

Kristiansen, K. & T.B. Larsson. 2005. The rise of Bronze Age society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Larsson, T.B. 1996. The horse and the wheel, in A. Knape (ed) Kult, Kraft, Kosmos, 45. Stockholm: Statens Historiska Museum.

Lindsay, J. 1972. Origins of Astrology. New York: Barnes & Noble.

Lutz, J., Pernicka, E., Pils, R., Tomedi, G., Vavtar, F. 2009. Geochemical characteristics of copper ores from the Greywacke Zone in the Austrian Alps and their relevance as a source of copper in prehistoric times. in Die Geschichte des Bergbaus in Tirol und seinen angrenzenden Gebieten, K. Oeggl & M. Prast, eds., Proceedings of the 3rd Milestone-Meeting of the SFB HiMAT, Innsbruck, 175–181.

MacDonald, J. 2000. The Arctic Sky. Iqaluit: Nunavut Research Institute.

Malmer, M.P. 1981. A Chorological Study of North European Rock Art. Antikvariska serien 32.

Maunder, E.W. 1913. The origin of the constellations. The Observatory 36: 329–34.

Meller, M. 2002. Die Himmelsscheibe von Nebra –ein frühbronzezeitlicher Fund von aussergewöhnlicher Bedeutung. Archäologie in Sachsen-Anhalt. Band 1: 7-20.

– 2004. Die Himmelsscheibe von Nebra, in H. Meller (ed.) Der Geschmiedete Himmel: 22–31. Stuttgart: Theiss.

– 2013. The Sky Disc of Nebra. In Harry Fokkens and Anthony Harding (eds), Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age. Oxford: OUP Oxford, 266–8.

Nagy, Gy. & P.D. Valavanis. 1993. The sun in Greek art and culture, in M. Singh (ed.) The sun, symbols of power and life, 281–95. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Navarro, R. & M.A. Losada. 1997. Shape of stars and optical quality of the human eye. Journal of the Optical Society of America. A 14: 353–59.

Neugebauer, J.W. 1987. Die Bronzezeit im Osten ├ûsterreichs. St. Pölten/Wien: NP Verlag.

Ovenden, M.W. 1966: The origin of the constellations. The Philosophical Journal 3 (1): 1–18.

Pásztor, E. 2014. Nebra Disc. In Handbook of Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy, edited by C. L. N. Ruggles, 1349–56. Berlin: Springer.

Pásztor, E. and C. Roslund, 2007. An interpretation of the Nebra Disc. Antiquity 81: 267–78.

Pernicka, E. 2010. Archäometallurgische Untersuchungen am und zum Hortfund von Nebra. in Der Griff nach den Sternen. Wie Europas Eliten zu Macht und Reichtum kamen, F. Bertemes & H. Meller, eds., Internationales Symposium, Tagungen des Landesmuseums für Vorgeschichte Halle (Saale), Band 5/II, 719–734.

Pernicka, E., Wunderlich, C.-H., Reichenberger, A., Meller, H., Borg, G. 2008. Zur Echtheit der Himmelsscheibe von Nebra – eine kurze Zusammenfassung der durchgeführten Untersuchungen. Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt, 38, 331–352.

Probst, E. 1996. Deutschland in der Bronzezeit. München: C. Bertelsmann.

Rogers, J.H. 1998. Origins of the ancient constellations I: The Mesopotamian traditions. Journal of the British Astronomical Association 108: 9–28.

Roy, A.E. 1984. The origin of the constellations. Vistas in Astronomy 27: 171–97.

Schlosser, W. 2002. Zur astronomischen Deutung der Himmelsscheibe von Nebra. Archäologie in Sachsen-Anhalt 1: 21–3.

– 2003. Astronomische Deutung der Himmelsscheibe von Nebra. Sterne und Weltraum 12: 34–40

– 2004. Die Himmelsscheibe von Nebra, in H. Meller (ed.) Der Geschmiedete Himmel: 44–7. Stuttgart: Theiss.

Schwarz, R. 2004. ├äxte aus dem hohen norden – zur Geschichte der Bronzeaxt aus Hermannshagen, in H. Meller (ed.) Der Geschmiedete Himmel, 178–9. Stuttgart: Theiss.

Sprockhoff, E. 1930. Zur Handelgeschichte der germanischen Bronzezeit. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Zsigmond, Gy. 1999. Égitest és néphagyomány (‘Celestial objects and folk heritage’ summary in English). Csikszereda. Pallas-Akademia Könyvkiadó.

Links to external sites

Nebra Ark Visitor Centre (English)

Nebra Ark Visitor Centre (German)

UNESCO Memory of the World Register (2013)

“An_interpretation_of_the_Nebra_Disc” by Emília Pásztor and Curt Roslund (2007)

No multimedia content published

Currently there is no multimedia content published for this case study