Category of Astronomical Heritage: cultural-natural mixed

Hortobágy Puszta and astronomy in shepherding practices

Presentation

Geographical position

Country: Hungary

Hungarian name of the World Heritage Area: Hortobágy Nemzeti Park—a Puszta

English name of the World Heritage Area: Hortobágy National Park—the Pusta

Fig. 1. Aerial photo © Szilvia G┼æri

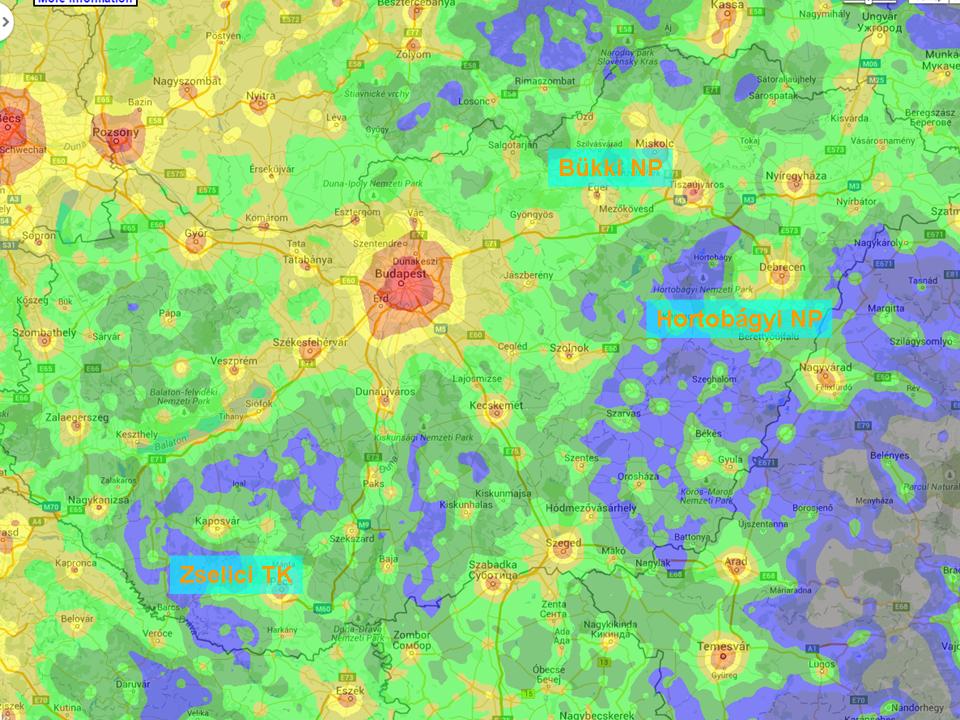

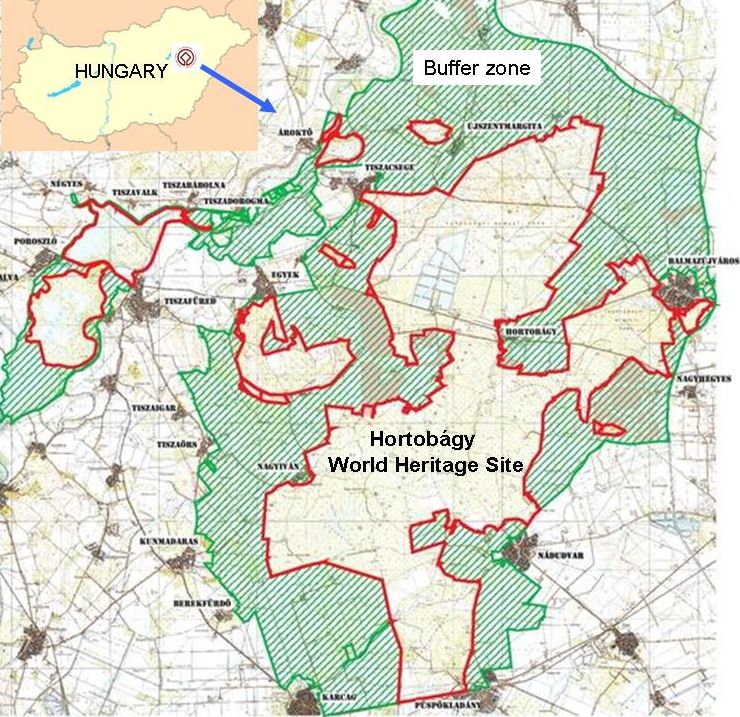

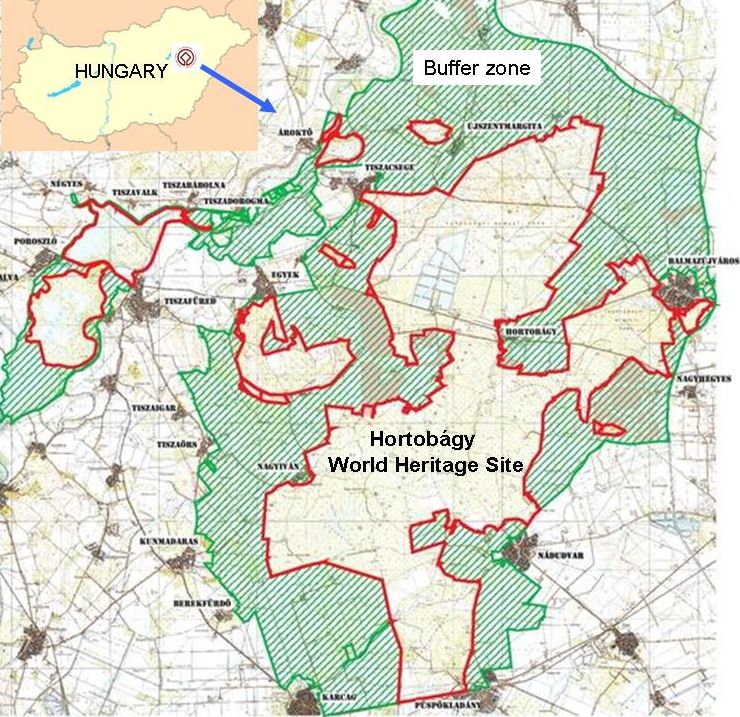

The Hortobágy Puszta is a plain located in the Middle-Tisza region and forms part of the Great Hungarian Plain. Administratively, most of its territory falls within the Hortobágy and Nagykunság regions. The World Heritage Site covers 74,865 ha and comprises a large contiguous area together with various smaller sub-areas partly within the administrative districts of 21 different settlements.

Fig. 2. Map of Hortobágy World Heritage Site

Location

Centre: Latitude 47° 33′ 31″.20 N, longitude 21° 03′ 20″.20 E

North-east corner: Latitude 47° 44′ 38″.15 N, longitude 21° 23′ 04″.05 E

South-west corner: Latitude 47° 19′ 23″.00 N, longitude 20° 37′ 25″.89 E

General description

The Hortobágy Puszta

The Hortobágy Puszta is located in the Great Hungarian Plain in the eastern part of the country. Hortobágy National Park, the first National Park to be declared in Hungary, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and also a silver-rated IDA Dark Sky Park. It is a unique example of a natural and cultural landscape both created and sustained by shepherding practices. It preserves these traditional sheep grazing practices and showcases a harmonious relationship between nature and man that stetches back over more than 5000 years.

An important part of this heritage is the celestial knowledge of the shepherds of the Puszta. Shepherds used to graze their flocks on the plains (pusztas), far from settlements, where they oriented themselves in space and time with the help of stars up until the use of clocks became commonplace. Observing the ever-changing sky during the day also formed the basis of the shepherd’s weather forecast.

The Hortobágy Puszta is a large floodplain whose current geographical appearance results from the frequent shifting of rivers during the Quaternary period, together with their sedimentation and surface-forming processes. It is considered to be one of the driest regions in Hungary and agriculture is also curtailed owing to its saline soils. The grazing livestock here has adapted to the various saline pastures, meadows and wetlands. The horizon is rarely obscured by trees, settlements or even powerlines. This creates an unquestionably picturesque landscape, and the sustainable land use has helped to preserve its unique biodiversity. Only a small population lives permanently in the area, but hundreds of shepherds continue to graze their flocks here between April and October. Their traditional shepherding practices, social customs and craftsmanship are also part of their intellectual heritage.

The ecosystem of the Pannonian Lowlands—the eastern part of the Carpathian Basin—bears striking similarities to the Eurasian steppe, to which it was once closely connected through flora corridors (Budapest and Ulan Bator lie almost at the same latitude). The Hortobágy landscape is virtually flat: a combination of alkaline marshes, meadows, dry alkaline pastures and remnant loess-steppe vegetation. These form a mosaic of habitats. In fact, Hortobágy is the largest alkaline area in Europe apart from the Volga-delta region. It is also the largest contiguous remnant native grassland area in the continent, and traditional grazing and shepherding practices survive here. Traditional buildings reflecting ancient pastoral activity are scattered among the pastures of Hortobágy.

Fig. 3. Migratory birds resting in the area. Photograph © Attila Szilágyi

Hortobágy is most famous for its rich avifauna. There are 159 nesting species plus an additional 178 species that are regular or irregular visitors. Hortobágy is generally accepted as the best bird-spotting location in Hungary (and possibly in the whole Carpathian Basin) as well as the most important IBA (Important Bird Area). Migration is particularly significant: for instance, Hortobágy is on the only inland migration route across Europe of the dotterel (Charadrius morinellus), which rests and moults here; there are regular sightings of the pale harrier (Circus macrourus) and during the 20th century there were 12 sightings of the slender-billed curlew (Numenius tenuirostris), now probably extinct.

The scale of migration is remarkable too: between 100,000 and 300,000 grey geese (Anser sp.), about 100,000 cranes (Grus grus) and between 50,000 and 200,000 ruffs (Calidris pugnax) stop over at Hortobágy. Hundreds of thousands of ducks of various species also stopped over here between 10 and 20 years ago, but recently their numbers have been significantly reduced. Many of the important breeding and nesting bird species (geese, crane, crakes etc.) and various other species, especially many rare insects, are pollution sensitive.

The Hortobágy Puszta is easily accessible by both road and rail.

The astronomical knowledge and traditions of shepherds at the end of the 20th century

Ethnographic records confirm that Hungarians once had extensive astronomical knowledge, and the traditions of the shepherds of the Hortobágy Puszta preserve some of the last fragments of this knowledge. Familiarity with the night sky was crucial for shepherds, as they often grazed their flock at night, far away from settlements. Here they could only navigate in time and space with the help of the stars. “Navigating like a shepherd” meant being knowledgeable about the stars.

Fig. 4. Old postcard representing shepherds’ star lore.

Shepherds also performed other types of work on clear nights when the moon shone brightly. They harvested dewy crops during droughts in order to keep the grains together; they grazed working animals until dawn; and they often fished at night using torches to lure the fish. They used the stars to guide them to collect “drenched” hay when a long drought hit the area.

The shepherds’ knowledge and tales of the night sky, and their traditional names for night-sky objects, have been slowly fading away since the use of clocks became widespread. However, the following were recorded at the end of the 20th century:

- The Evening Star (the planet Venus or sometimes the star Arcturus), is widely known, not only among shepherds.

- The constellation Ursa Maior (Big Dipper or Plough) is well known as a wagon with four wheels and a curved shaft made out of three stars. From the position of the wagon-shaft shepherds could determine not only the hour of the night but also the north direction, so it helped with navigation as well.

- The Pleiades are mostly used for determining the type of work according to the time and season.

- Orion is one of the best-known constellations. In Hungarian folklore, it is called the “Kaszáscsillag”, or reaper constellation. Written sources from the 15th century already mention its name as kaza hug. The four outer stars indicate the boundaries of the mowing area, in the middle of which the three reapers mow the harvest. The Hortobágy shepherds believe that Sánta Kata (Sirius) is hurrying clumsily after the three mowing harvesters, but no matter how fast she hobbles, she can not catch them up to give them the food she is carrying. In Hungarian folklore, the twinkling of Sirius is associated with limping.

- Félkenyér (“half bread”) is a constellation near the end of the shaft of the wagon (Ursa Major), which probably corresponds to Corona Borealis or a few stars in the constellation Draco. Gáspár and Es┼æcsillag (“rain star”) are unidentified asterisms possibly near to Perseus. The Ox Seeker or Ox Stealer star was most likely the planet Venus, according to the journal of the ethnographer and naturalist Ottó Herman (Herman 1914). Shepherds believed that it warned them to gather in the oxen they had let out to graze at night, since highwaymen usually steal oxen when this star rises.

Fig. 5. Hungarian shepherds, József Molnár and Imre Szönyi. Photograph © István Gyarmathy

- Shepherds call the constellation Cygnus the Cross Star.

- People from Hortobágy also consider meteors entering the Earth’s atmosphere to be stars and call them shooting stars. The are believed to foretell the death of men, women and children depending on their brightness. Comets are also regarded as stars, and can foretell of wars.

Fig. 6. Star map with old Hungarian names and illustrations of constellations drawn by Sándor Nagy, the famous graphic designer of the period of secession, 1915.

According to ethnographic research in the 1950s, the Milky Way was still known by many names at that time, including “The Road of Armies” and “Scatterstraw” (since it reminded people of straw scattered along the road during harvest). In Hungarian folktales, the age of old women is compared to that of the Milky Way in the expression “older than the highway”. In some areas, folk tradition still states that the Milky Way was the road of an ancient, famous warlord, or that it indicates the direction from which the Hungarians came from Asia.

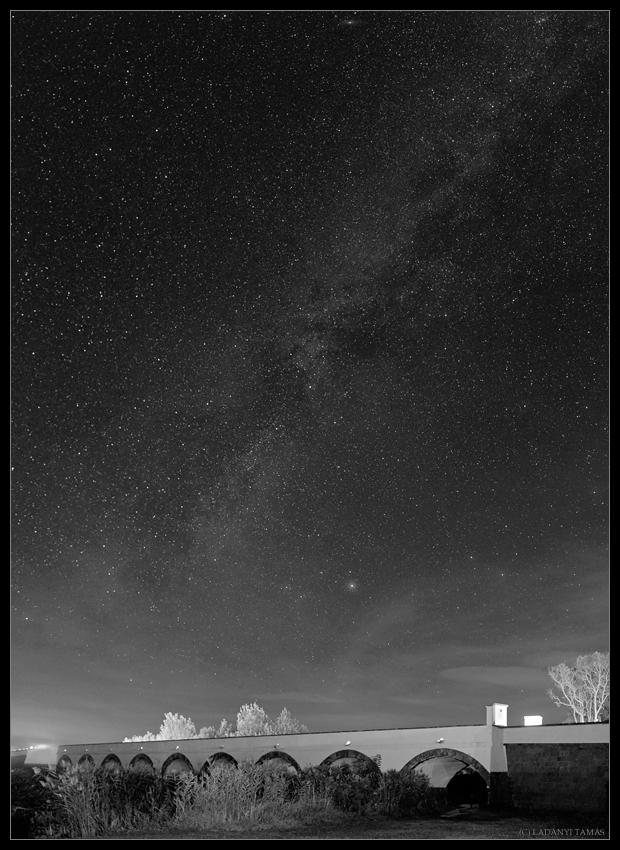

Fig. 7. The Milky Way behind a characteristic Hungarian sweep. Photograph © Tamás Ladányi

Brief inventory

Mounds

The number of mounds in the Great Plain is estimated to be around 3,500, mainly in the Tiszatúl region. About 1649 mounds are registered in the Hortobágy area. These mounds are artificial constructions but they have exceptional botanical and zoological value in addition to their archaeological, historical and cultural significance. They can be tells, burial mounds, guard stations, or border markers. Their diameters vary from 20 m to 90 m and their heights from 0.5 m to 12 m. Most of them are now covered with important flora and form the habitats of protected animals, making them a truly organic part of the landscape.

In terms of age and size, we need to differentiate the large prehistoric kurgans from the small Sarmatian mounds of Roman imperial times (AD 200–300) which occur in larger numbers, mostly within tumulus cemeteries such as Poroshát and Kockakút.

The kurgans are special burial mounds built over the graves of nobles by the eastern European nomads who arrived in the grasslands of Tiszántúl between the Late Copper Age and the Early Bronze Age (3300–2600 BC). They are typical elements of the Hortobágy landscape, usually to be found along the shores of former waterways, one after the other. The kurgans around Hortobágy are the westernmost occurrence of this particular form of burial from the Eurasian steppes.

Several secondary burials (e.g. Sarmatian) and other tombs of the migration age were found during the excavation of these kurgans. The conquering Hungarians arriving in the Carpathian Basin also liked to use them for burials. Later, these mounds, being the highest points in the area, became the first places to erect churches upon during the Árpád dynasty. They were also used as border markers on the plains during Medieval times. The first detailed maps of the 16th century mark the most significant mounds and land-surveying points were placed on them. The name Kunhalom has become widespread owing to literary influences dating from the 19th century. This is still the most commonly used name for these mounds despite the fact that very few of them actually belonged to the settling Kuns.

Standing buildings

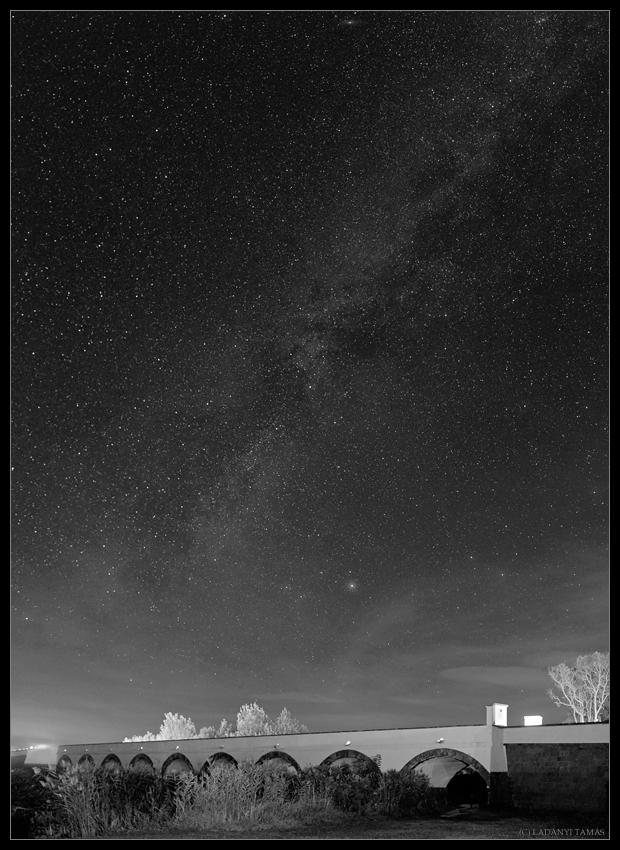

Fig. 8. The famous nine-arched bridge. Photograph © Tamás Ladányi

Kurgans and other prehistoric earthworks have been present in the Hortobágy area since 3000 BC. Settlements and monasteries were built much later in the 10th and 11th centuries, but most of them were destroyed during the Turkish occupation and only their remains are left today (e.g. at Papegyháza and Ohat-Telekháza).

Some of Hortobágy’s most iconic elements are the taverns along the main roads (e.g. Nagyhortobágy tavern and cart shelter; Kishortobágy, Kadarcs and Meggyes taverns) and the stone bridges over rivers (Nagyhortobágy (nine-arched) stone bridge; Szent Ágota bridge).

The taverns are important buildings representing the economic boom of the 18th century located along the most important trade, postal and herding routes, a half-day or full day’s walking distance from each other. Earlier wooden and plank bridges were replaced by stone structures to provide a safer passage for traffic. Wells with sweeps, originally built to provide waters for animals, are also symbols of the Hungarian puszta. The shepherds’ buildings in connection with grazing livestock husbandry are also iconic parts of the shepherding culture and harmonious elements of the Hortobágy Puszta.

History

The first eastern nomadic groups appeared in the Great Hungarian Plain in the Neolithic, around 5000 BC. However, Tiszántúl—and therefore the area of Hortobágy—experienced larger, successive waves of immigration from the eastern steppes at the end of the Copper Age, between 3500 and 2800 BC. It is clear that these communities emerged from the eastern European nomadic communities of the Yamnaya (Pit grave) culture and continued their nomadic life in this area, where the landscape was similar. They are likely to have been transhumant, living and grazing their flocks in Hortobágy and similar lowlands during the summers but using the highlands neighbouring on to Hortobágy as their winter accommodation and pasture land.

The emergence of the distinctive Hortobágy cultural landscape can be linked to these early settlers and their livestock farming. ‘Tells’, low mounds found on the World Heritage Site, indicate the location of Neolithic settlements. ‘Kurgans’, or burial mounds, dating back to 3000 BC remain conspicuous in today’s landscape. They covered the graves of chieftains and were full of treasures. The importance of Hortobágy lies not only in the preservation of these monuments, but also in the fact that it represents the westernmost occurrence of the ancient steppe lifestyle and culture in Eurasia.

From the bones of their prey found at archaeological sites we can conclude that steppe fauna species such as Equus ferus gmelini and Equus hemionus anatolicus also lived in the Hortobágy area between about 3000 and 1000 BC.

Most of the Hortobágy area remained treeless even during the onset of the colder and wetter climate of the Subatlantic Period, when many parts of the Great Plain became overgrown by forests; and so it has remained until today. The essentially treeless, open grassland results from the dual effect of the grazing of livestock, which has remained the typical land use of Hortobágy, and the alkaline soils, which have prevented the spread of woodland vegetation. In other words, it results from a combination of the natural features and the land use that have characterised this area for thousands of years.

Fig. 9. Shepherds standing by a characteristic Hungarian sweep. Photograph © László Lisztes

The transhumant pattern of land use—the alternating use of pastures according to the change of season—continued as the Carpathian Basin was successively occupied by Pre-Scythians, Scythians, Sarmatians, Huns and Avars. All of them cultivated the neighbouring lands and used the Hortobágy area only as their summer home and pasture. Some of the later ethnic groups re-used the kurgans as secondary burial places, and even some Christian churches were built upon them.

The Hungarian settlers of the Middle Ages populated Hortobágy more densely than today, but still sparsely compared to other areas at the time. As the result of the depopulation starting in the 14th century, the central area had become almost completely deserted by the end of the 16th century. Most of the abandoned villages were purchased by the city of Debrecen.

Hortobágy Puszta then became a free communal pasture where breeding livestock were kept and tended from the spring until the autumn. This centuries-old practice continues in the area. Although the communal pasture land has shrunk significantly owing to river regulations and the spread of agriculture since the mid-19th century, what remains is mostly preserved under the protection of the Hortobágy National Park.

Cultural and symbolic dimension

Hardly any permanent population lives inside the World Heritage Site, but the few hundred shepherds grazing their livestock in the area maintain a cultural and intellectual heritage unique to the Hortobágy Puszta. They acquired their knowledge through practice over the years: they learnt how to care for grazing livestock, to tend sick animals, to construct simple buildings fit for their needs, to prepare their meals and make their tools. Their clothes are unique, adapted to their working style; their beliefs and habits are archaic.

The seemingly infinite puszta with its boundless sky and myriads of stars shining down at night has an otherworldly effect on the people living there. They typically feel as if they are at the centre of the universe, and this perception has become an important part of their world-view. Accordingly Hungarian farmers and shepherds believe there are parallel worlds above and below ours, which are similar to it.

However, more everyday practicalities are regulated according to the Sun and other celestial bodies. The movement of the Sun is pivotal and sunrise and sunset, together with various other phases of the lighting during the day, are given explicit names. Whatever the season, noon is precisely determined by the shortness of shadows and the position of the Sun.

Mythical tales help to impart folk knowledge about nature and practical advice based on experience: orientating oneself, scheduling one’s activities, and keeping track of the rhythms of nature and adapting to them.

The shepherds often personify celestial objects and phenomena, and even winds. These can be visualised as humans, for example as an elderly mother returning home after finishing her work. People living in the puszta can have encounters with “beings” of the upper world almost every day and witness their activities in the daytime or night sky. In a sudden downpour, for example, the long tail of a ferocious dragon may graze the ground in the form of a small, but destructive whirlwind (called tromba). According to the shepherds’ belief, there is an actual dragon living inside such a whirlwind, and it destroys everything in its way.

Hortobágy is often associated with mirages that create the illusion of strange shapes on the horizon on a sultry day. It is the home of the Fairy of the Puszta, the mirage. She is not scary, but illusive. According to legends the Sun, the Wind and the Clouds all compete for the love of the Puszta Fairy. Many poets and writers have travelled there just to write about this quest for love. “Lately, even the Mirage became intimidated in the Hortobágy. When there weren’t as many farms as today, she played here and there. But today I rarely see her anymore”, said an old shepherd.

Shepherds could witness every detail of the sky, the playful passing of clouds, the brilliance of clear starry nights, and the undisturbed journey of the Sun on the endless sky of the Puszta. These observations enriched their knowledge of nature.

The stars also played a significant role in foretelling the weather, especially on memorable days. Shepherds could predict not only the winter weather, but also the weather for the next year based on the position of the stars on St. Michael’s Day (September 29). Many shepherds sourced their forage for the winter based on these predictions, even at the beginning of the 20th century.

St. Michael’s Day is also important as the end of the economic year. On this day, shepherds gathered the herds they had let out to graze freely on the pastures the previous spring, on St. George’s Day (April 24). On St. Michael’s Day the shepherds had to account their herds; they received payment and made new contracts for the next season. This was the biggest day of celebration in Hortobágy, when shepherds held parties and festivals. In addition, markets were often held on this day so that shepherds could purchase new equipment. Various weather-related proverbs relate to St. Michael’s Day: for example, “St. Michael’s horse is rimy, it’ll bring the winter!”

As the seasons progress, the colours of the Puszta turn from the green of spring to red, then golden yellow by the end of the summer. The massive migrations of birds every spring and autumn are characteristic elements of the Puszta, and also part of its outstanding natural value. The crane and wild goose migrations are highlights of Hungarian wildlife and also internationally renowned attractions among bird enthusiasts. Sometimes tens of thousands of birds fly together at dawn or dusk. Around 95% of the cranes migrating across Hungary stop to rest at Hortobágy: the record number staying overnight all at once is about 120,000. The native wildlife of the Puszta is fundamental to the Hortobágy landscape, and essential for its long-term existence.

The Hortobágy Puszta as a whole has become a symbol of Hungarian national identity. Its unique history, valuable wildlife and special folklore have been further enriched through literature and art. The particular lifestyle of the shepherds and its cultural significance evoked great interest among early ethnographers and writers and the extensive material they gathered and created has become a fundamental part of this intellectual heritage, alongside the artistic works depicting the wonders of the Puszta and the material culture of the Hortobágy shepherds themselves.

The names of stars and constellations preserved at Hortobágy allow us to gain insights into the diversity of folk mentality and understand how people perceived and comprehended the world. This knowledge is essential to understand the history of astronomy, and it would be an irreplaceable loss if it disappears.

Comparative analysis

The Carpathian Basin can be regarded as a unified region in terms of astronomical observations owing to its limited size. Yet, ethnographic studies show there is a noticeable difference between the traditions of the highlands and the lowlands. Those living in the Great Plain and the Hortobágy—the flat lands—have a much richer astronomical heritage than the people of the mountains.

Shepherds do not recognise significantly more stars than others, but they had a greater in-depth knowledge of their use in aiding timing and orientation. This knowledge was of great importance before watches came into common use. They could confidently point out every star they knew on any night.

A person’s profession had an impact on their astronomical knowledge, as does economic necessity. Amades (1994) collected alternative names for stars among Catalan shepherds, fishermen and farmers at the beginning of the 20th century. Not only were the names different, but they also arranged constellations differently. The timing of harvest and other agricultural work was important for farmers, while fishermen needed to know how to navigate out in the open sea. For shepherds, the vital thing was to pick the right time to gather and let out their flocks.

If we compare traditional astronomical knowledge in different regions of Hungary, people in Hortobágy know the most stars and constellations—16 in total. A similar number of stars is known only in western Moldavia, within modern Romania, where a small group of ethnic Hungarians live in strong cultural isolation and have preserved their traditional knowledge. Regarding alternative names, only Moldavia with 165 variants surpasses Hortobágy with 50. Ethnographic research suggests that individuals usually knew about seven asterisms each, generally including Ursa Major, the Pleiades, the Morning Star (Venus), the Evening Star (Venus), and the Milky Way, and also including meteors and comets which they also regarded as stars.

Most Hungarian names and variants are related to the most famous stars and constellations. The number of variants is in parentheses: Milky Way (23), Pleiades (18), Evening Star (11), Ursa Major (9). Ottó Herman also noted in his collection of star names (Herman 1914) that not only could certain stars have different names from region to region, but entirely different stars, visible in separate seasons, could share the same name.

The roots of ancient Hungarian words for stars can be found in their folk names. Comparing the names of stars and constellations can also draw attention to certain intercultural links. For example, László Mándoki’s research (1958, 1962, 1965) has revealed that Hungarians learned the names for the Milky Way referring to “a road scattered with straw” in the Carpathian Basin when farming became the basis of their livelihood. This type of naming for the Milky Way is typical among agricultural communities in the Mediterranean region, mostly in the Eastern parts. Mándoki even suggests this type of naming comes from Anatolia in the Caucasus where the ancient wheat varieties originate. He claims that the spread of this type of naming in Europe is surprisingly similar to the way wheat varieties spread across the continent.

Mándoki also studied the variant names for Orion Három Kaszás (“Three Reapers”) and Kaszások (“Reapers”) and their related interpretations. These names are most common among the Germanic and Slavic languages, but they can also be found in northern Italy in Italian-speaking areas such as Ladinia, Trentino and Venetia. These variants have Classical Greek roots and seem to be characteristic of the central and eastern parts of Europe, but have spread somewhat into western Europe.

The idea that the stars of Orion’s Belt resemble a wand or staff goes back to Classical Greek traditions since this is also one of the Greek names for these stars. There are few comparative studies on this subject, but similar variants, referring to a scythe and a wand, are also used by shepherds, despite not being of Hungarian origin nor even local to this area. Most star or constellation names are not solely Hungarian but shared among many European nations thanks to their common history. This common intangible astronomical heritage of the central and eastern European nations is mostly preserved by the shepherds of Hortobágy.

Apart from their names for stars, Hungarian shepherds have traditions for important dates (e.g. St George’s Day on 24 April) indicating their integration into European culture. St George’s Day is the first day of spring in most of Europe, and is celebrated by various Christian churches as the day of Saint George the dragon killer. However, the shepherds’ traditions and beliefs are more closely related to Roman shepherding rituals. This is the first day when the animals are let out onto the pastures in Hungary and neighbouring countries, usually herded with a green twig to boost their growth and numbers. The day is similarly celebrated among Ruthenes, southern Slavs, and Romanians.

Authenticity and integrity

There are 187 (including four highly protected) archaeological sites registered in the area of Hortobágy. However, there are likely to be at least two or three times as many yet to be discovered. These sites contain the tangible remains of more than 7000 years of history. Since the middle of the Neolithic, this area has been continuously inhabited by various ethnic groups with different material and intellectual culture, creating a complex cultural landscape that is unique within Europe.

Hortobágy has a very distinctive natural landscape and land use that has been preserved for millennia. Indeed, traditional methods of tending grazing livestock (of mostly traditional breeds) and leaving unused areas in their natural state still exist today, and these have helped maintain the integrity of the landscape. Traditional buildings and structures such as wells with sweeps, taverns, bridges and seasonal housing preserve not only past styles but also construction materials such as clay and reed. All this has been inspiring countless artists, poets and writers throughout the centuries.

Documentation and archives

József Lugossy (1812–1884) was a pioneer of scientifically collecting and studying the Hungarian names of stars in the 1840s and 1850s. He was a literature teacher who published several star names in his articles in 1855, and even put out a call for his fellow scholars to collect names. Unfortunately, his great manuscript on the comparative knowledge of stars was lost. A typical shortcoming of early studies was that they failed to record the exact location of the collected materials, so the data are not suitable for comparison.

Lajos Kálmány (1852–1919) was the first after Lugossy to collect the folk names of stars together with their scientific identification and possible interpretation. The most significant aspect of his work was that he also collected and published the legends related to these stars and constellations.

The polymath Ottó Herman (1835–1914) was the first to devote an entire chapter to shepherds’ astronomy in his work entitled “The Hungarian shepherds’ linguistic heritage” published in 1914. However, the title is misleading because most of the data upon which the work is based cannot be proved to be from shepherds. This was fortunately not the case for the material he collected between 1895 and 1899, which was reviewed critically by László Mándoki. The publication of these data is significant because it gives a nationwide overview of the astronomical knowledge of shepherds and sought to link the Hungarian names of stars and constellations with their scientific (Greek or Latin) names recognised internationally.

According to Ottó Herman’s research, shepherds at the end of the 19th century knew of 11 identifiable constellations including Ursa Major (Big Dipper or Plough), Orion (as “the Reaper”), and separately Orion’s Belt, Cygnus, and Cassiopeia; theMilky Way; the planet Venus (separately as the evening and the morning star); and several individual stars including Sirius, Polaris and Alcor (80 UMa) which is the faint star next to the central star of Ursa Major’s shaft. Six star names could not be matched with their scientific names.

Management and use

Present use

The Hortobágy Puszta is one of the most important and diverse wetland habitats in Hungary. It is a highly favoured feeding and resting place, and the most important habitat for birds in the country. Several highly protected species nest in the area, while tens of thousands of cranes stop to rest here during the migration period.

State of conservation

In recent decades, the National Park management has carried out the rehabilitation of thousands of hectares of wetland and grassland habitats and keeps maintaining them. The rehabilitation of marshes, grasslands and the backwaters of the river Tisza were carried out through international collaborations and are of great importance both in Hungary and in Europe.

Main threats or potential threats

The main feature of the Puszta is the low number of landscape elements and their lack of diversity. This particularity of the area would look poor and gloomy elsewhere but in case of Hortobágy, this simple environment makes it unique. Potential threats are:

- Alien or collapsing structures

- Growing urbanisation

Bird life is one of the most important aspects of Hortobágy. Thanks to the vast and diverse wetland habitats, it is one of Europe’s most significant continental bird sanctuaries. Potential threats are:

- Certain human activities: cultivation of grasslands, ploughing, overgrazing, direct disturbance

- Light pollution

Traditional livestock husbandry. The sight of constantly moving flocks of sheep and herds of cows and horses grazing on the pastures forms an integral part of Hortobágy’s landscape from the spring through to the autumn. This is enhanced by the spectacle of precious wildlife such as migrating cranes. Potential threats are:

- Lack of adequate composition and quantity of livestock

- Fragmentation of the land

- Modern grazing instead of the traditional way

- Disappearance of shepherds and their culture

The puszta provides a variety of optical spectacles such as:

- The mirage, which is an iconic element of Hortobágy. This special light phenomenon generates strange shapes on the rim of the horizon.

- The changing colours of the seasons. with the green landscape of spring turning red by the middle of May and golden yellow at the height of summer. This is enhanced by the red disc of the sun at dawn and dusk, and the gleaming river Hortobágy adds a silvery touch to the view in the middle of the day.

- The spectacular dome of the starry night sky, almost complete because of the flat horizon.

Potential threats are:

- Anything threatening the integrity of the wide-open views and flat horizon, such as tall buildings or plantations of trees

- Light pollution

Archaeological sites are potentially threatened by:

- Ploughing

- Weeds

- Illegal prospecting with metal detectors

- Digging other than archaeological excavations

Standing buildings and monuments are potentially threatened by:

- Deterioration

- Change of owner or tenant

- Lack of tourism

The shepherding practices themselves are threatened by:

- Lack of professional shepherds (unpopular profession, education issues)

- Lack of appreciation of the profession—a precarious livelihood

- The disappearance of traditional clothing and craft products from everyday use

- Lifestyle changes, growing use of technology and mass products

- Certain intangible elements of the shepherds’ culture (e.g. beliefs) have faded away from their everyday life

Protection

The Hortobágy National Park was established in 1972 bringing a long-awaited official protection to the cultural heritage and the traditional land use in the area. The UNESCO World Heritage Committee inscribed the Hortobágy National Park area (74,820 ha at the time) on the World Heritage List in 1999. Act LXXVII of 2011 on World Heritage details the conservation status of World Heritage Sites in Hungary.

The World Heritage Site is almost entirely within the territory of the Hortobágy National Park, which also falls under many other international conventions and protection categories such as the Biosphere Reserve, Ramsar area and Natura 2000 area.

The area is also ex-lege protected, part of ecological networks subject to domestic legislations that were established to ensure its long-term preservation.

Context and environment

The National Spatial Plan classifies the Hortobágy National Park and its environment into the National Ecological Network, the Landscape Protection and the World Heritage Site.

The World Heritage Management Plan (not yet uploaded) has specific regulations for World Heritage Sites and Protected Areas including regulations for landscape protection and lighting.

Management, interpretation and outreach

National Park management

Fig. 10. The emblem of Hortobágy National Park

The Hortobágy National Park was established in 1973, but apart from the main 54.000 ha area, it only managed a few smaller nature reserves. Today, the National Park has expanded to 82,000 ha, of which 75,000 are part of the World Heritage Site. There are four additional protected areas and 20 nature reserves under National Park management, covering an area of approximately 155,000 ha in total.

The National Park deals with managing the assets of the area, for example coordinating the wildlife management. One of the largest contingent hunting grounds in the country operates in the Hortobágy National Park.

A new type of tourism framework, based on real ecotourism, has been developed in order to adapt to the changed ownership, legal and economic conditions. This new framework not only determines the National Park’s development, but also regulates the activities of any tourism organisations or businesses in the area. The main principle of the Park’s ecotourism is that the cultural and natural elements of the area are organic parts of the landscape.

Cultural Heritage Tourism

The Hortobágy Shepherd Museum is one of the most popular places presenting cultural values in the area. The Shepherd Museum showcases the characteristics of the grazing livestock husbandry and the elements of the shepherding lifestyle typical in the 19th and 20th centuries. The exhibition presents a bygone world with lifelike figures, paintings, photos, film screenings and audio material. The building that now houses the museum was built at the end of the 18th century and functioned as a cart stopover where travellers and their animals rested.

The Hortobágy Crafts Hall is attached to the visitor centre. Among the craftsmanship typical of this area, visitors can glimpse into the secrets of leather-strap manufacturing, costume making, hat making, lace making, felting, cheese making, weaving, wood carving, puppet making and beading in the Crafts Hall. There are always workshops and visitors can try some of the simpler techniques.

The Puszta Zoo was established in 1997 by the Hortobágy Nature Conservation and Gene Protection NGO in order to showcase traditional breeds of domestic animals and promote the husbandry of these breeds in the country. The Zoo also holds special events, mainly on memorable days, such as the National Goulash Cooking Competition and Shepherd Festival at Easter or Pentecost, Midsummer Night, Stork Welcoming Day in March, or Swallow Farewell Day in September.

The oldest element of the Puszta’s image is the romanticism around the life of herdsmen and cattlemen. The simplicity of their life and the freedom and toughness of these people and their animals once evoked respect and awe from the general public. It is important to emphasize that most of the remaining shepherds, about 300 of them, live and work in the Hortobágy. These shepherds have had to adapt their work to the technological advancements, standards and regulations of the 21st century. Nonetheless, shepherding is their livelihood, they take pride in their professionalism, and veer away from the people who only play the role of a shepherd for the tourists.

Starting from the Máta Stud Farm, visitors can enjoy a cart ride and see all the typical domestic animals of the Hortobágy Puszta such as breeding stallions, herds of Hungarian Grey Cattle and Buffalo, flocks of racka (a typical Hungarian breed of sheep), groups of mangalica (Hungarian pigs), and even a “Quintet of the Hortobágy Puszta”, a spectacular show put on by local cattlemen.

Ecotourism

The Hortobágy Wildlife Park showcases wild animals that were common to the Puszta before the first human settlers arrived. These include wild horses, wild cattle and rare bird species all set in a natural environment.

Event Tourism

Apart from daily activities, the Hortobágy National Park management also organizes annual events, usually related to memorable days in the calendar. There are often animal presentations and auctions during these events.

- The herding on St George’s Day and St Demetrius’s Day usually take place at the Nine-Arched Bridge. Visitors can enjoy a parade of racka flocks, cattlemen, carts, carriage driving, the herding of Grey Cattle and a horse show at the Máta Stud Farm. Shepherds and shepherd boys from every corner of the Great Plain meet up at the National Goulash Competition and Shepherd Festival to demonstrate their skills. The National Shepherd Dance Competition and Shepherd Ball is also hosted during this Festival where different traditional shepherd dances are presented to the visitors.

- Hortobágy Equestrian Days take place at Máta Stud Farm where lovers of equestrian sports in Hungary can enjoy activities including the show of the cattlemen. Hortobágy herdsmen present the best of their herds at the Grey Cattle Animal Fair, organised by the Association of Hungarian Grey Cattle Breeders and the Hortobágy NGO.

The Hídi Fair is one of the most iconic events of the region organised by the Hortobágy Municipality. It is one of Debrecen’s town fairs, long known and renowned by local people. It was basically an animal fair, but an animal fair was unimaginable without a craft fair. The craftsmen from Debrecen and the surrounding area were involved, displaying their goods. After making a deal they would eat and drink in a fast-food or steak house. This tradition has been revived. The Hídi Fair is accompanied by cultural events and a series of programmes, which generally respect the spirit of tradition and folklore. A series of folk-music and folk-dance performances welcome guests upon arrival.

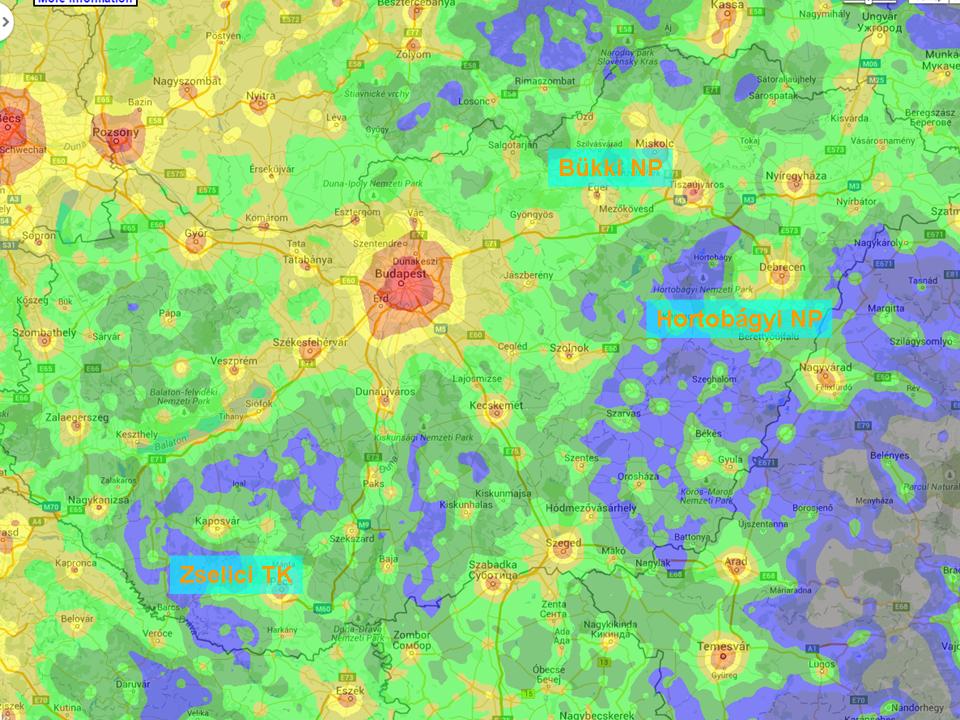

The Dark Sky Park and astrotourism

Fig. 11a. The emblem of Hortobágy Starry Park. © Hortobágy Dark Sky Park

Fig. 11b. Map of light pollution of Hungary with the dark-sky parks. © Hortobágy Dark Sky Park

The internationally renowned Hortobágy Dark Sky Park was established in 2011. The Hortobágy National Park has made several changes such as the reconstruction of the lighting system in order to preserve the ideal natural circumstances of the park. The management has also created binding regulations for neighbouring municipalities and farmers for any future project in proximity of the park.

Interest in astrotourism in the National Park has been growing gradually and most astronomical programmes are also linked to other attractions or events in the Hortobágy such as birdwatching tours, the Crane Migration Festival, Museums at Night, or even gastronomic activities.

Special programs are organised at the Máta Forest School where groups can learn about astronomy, traditions related to the stars, and the threats posed by light pollution. The National Park management also plans to build specific “Star Trails” and even an observatory to further diversify their astronomical attractions.

Fig. 12. The observatory at Máta. Photograph © Tamás Ladány

References

Bibliography (books and published articles)

AMADES, J. 1994 Des étoiles aux plantes: petite cosmogonie catalane. Carcassone: garae/Hesiode. Toulouse (XX. sz. elejei munka újraközlése)

ARADI Cs., Dunka B. és Veress L. (2000): A Hortobágy hasznosítása Történelmi kép A Hortobágy önállósítása A világörökség elvárásai - Magyar Tudomány 1467-1510.

BAK├ô E. (2002): A Hortobágy a magyar irodalomban - Debrecen

BALOGH I. (1943a): A hortobágyi pásztorkodás történeti múltja - Néprajzi Értesít┼æ 35: 97-112.

BALASSA Iván - Ujváry Zoltán szerk.: Néprajzi tanulmányok. A Hajdú-Bihar Megyei Múzeumok Közleményei 39. Debrecen. 812-816

BARNA G. (1972–74): Mitikus alakok a Hortobágy környéki falvak és a hortobágyi emberek hiedelemvilágában - In: Gunda B. (szerk.) A Hortobágy néprajzához - M┼▒veltség és Hagyomány 15-16: 273–298.

BARNA G. (1979): Néphit és népszokások a Hortobágy vidékén - Budapest

BARNA Gábor 1982. Népi csillagnevek és hagyományaik a Hortobágy vidékén. In: Balassa Iván-Ujvári Zoltán (szerk.) Néprajzi tanulmányok Dankó Imre tiszteletére - Debrecen 811-816.

BARTHA Lajos 2010. A csillagképek története és látnivalói. (Szerk. Vizi Péter.) Geobook Kiadó, Szentendre.

BÉRES A. (1976d): A Hortobágy néprajza - In: Kovács G. és Salamon F. (szerk.) Hortobágy a nomád pusztától a Nemzeti Parkig - Budapest 246-288.

BOD├ô I.: Zucht und Haltung der uralten ungarischen Haustierrasse auf der Steppe von Hortobágy - Domestikationsforschung und Geschichte der Haustiere - Akad. kiadó. Budapest. 1972.

BÓNA I. (1992a): Bronzezeitliche Tell-Kulturen in Ungarn - In: Bronzezeit in Ungarn - Forschungen in Tell-Siedlungen an Donau und Theiss - (Hrsg.: Meier-Arendt, W.) Frankfurt am Main, 9-42.

DÁM L. (2010): A Hortobágy puszta néprajza - In: Acta biologica Debrecina - Supplementum oecologica hungarica 97-129.

DANI J. - Horváth T. (2012): ┼Éskori kurgánok a magyart Alföldön - Archaeolingua Kiadó Budapest

DANI J. (2005): The Hortobágy in the Bronze Age - In: Juhász I. - Gál E. - Sümegi P. (szerk.): Environmental Archaeology in North-Eastern Hungary - Varia Archaeologica Hungarica XIX. Budapest, 283-300

ECSEDI I. (1914): A Hortobágy puszta és élete - Debrecen

ECSEDI I. (1929c): Éjjeli legeltetés és pásztort┼▒z a Hortobágyon - Néprajzi Értesít┼æ 21: 53-54.

ECSEDY I. (1979): The peoples of the pit-grave kurgans in Eastern-Hungary - In: Fontes Arch. Hung., Budapest

ERD┼ÉDI József 1970 Uráli csillagnevek es mitológiai magyarázatuk. A Magyar Nyelvtudományi Társaság Kiadványai.124. Bp.

GEWALT, W.: Europas Serengeti die ungarische Puszta Hortobágy - Das Tier IX. 1969. 1. sz.

GY├ûNGYVÉR E. -Hajdú Zs. 2005: The Neolithic and Copper Age of the Hotrobágy region - Dep. Of Geology and Paleonthology Univ. Of Szeged

GY├ûRFFY I. (1984): Nagykunsági krónika - Karcag

HERMAN Ottó 1914. Pásztor-csillagászat. In: Herman Ottó, A magyar pásztorok nyelvkincse. Bp. 624-631. Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár: http://mek.oszk.hu/06900/06994/06994.pdf

HERMAN O. (1898): ┼Ésfoglalkozások. 1. Halászat, 2. Pásztorélet - In: Matelkovics S. (szerk.) Az 1896. évi Ezredéves Kiállítás eredményei V. Budapest 651–763.

HILBERS, D. 2008: Hortobágy - The Nature Guide to the Hortobágy and Tisza river floodplain - Hungary - Crossbill Guides No. 7., The Netherlands

HORVÁTH, Tünde – Dani, János – Pet┼æ, Ákos – Pospieszny, ┼üukasz – Svingor, Éva 2013. Multidisciplinary Contributions to the Study of Pit Grave Culture Kurgans of the Great Hungarian Plain. In Heyd, Volker – Kulcsár, Gabriella – Szeverényi, Vajk (eds.): Transitions to the Bronze Age. 153–181. Budapest, Archaeolingua Alapítvány.

LUGOSSY József: ┼Ésmagyar csillagismei közlemény. = Uj Magyar Múzeum 5. folyam 1855. 1. füz. pp. 54-75.; 2. füz. pp. 113-146.; 5. füz. pp. 250-260.

LÜK┼É G. (1939): A hortobágyi pásztorm┼▒vészet - A Debreceni Déri Múzeum Évkönyve 1938. 101-130. + 24 m┼▒melléklet

M. NEPPER I. - S┼æregi J. - Zoltai L. (1981): Hajdú-Bihar megye halomkatasztere II. Hajdúság - Das Hügelkataster des Bezirkes Hajdú-Bihar. HMÉ IV., 91-129.

M. NEPPER I. (1968): Szkítakori leletek a Déri Múzeumból (Adatközlés) Scythian finds in the Déri Museum (Publication of data) - In: Déri Múzeum Évkönyve 1966-1967., 53-65.

MADARASSY L. (1928): A hortobágyi pásztor és a természetvizsgáló - Ethnographia 39: 40-43.

MAGYARI E. 2011: Late Quaternary vegetation History in the Hortobágy Steppe and Middle Tisza Floodplain, NE Hungary - Studia bot. hung. 42, pp. 185–203

MAHUNKA, S. (ed.) 1981: The Fauna of the Hortobágy National Park Vol. 1. - Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest

MAHUNKA, S. (ed.) 1983: The Fauna of the Hortobágy National Park Vol. 2. - Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest

MÁNDOKI László 1965. Herman Ottó Csillagnév gy┼▒jtései Janus Pannonius Múzeum Évkönyve

MÁNDOKI László 1962 A Szalmás út. ln: A Janus Pannonius Múzeum évkönyve. Pécs 287-302.

MÁNDOKI László 1958. Az Orion csillagkép a magyarságnál. — Das Sternbild des Orions im Ungartum. Néprajzi Értesít┼æ. A Nemzeti Múzeum és Néprajzi Múzeum Évkönyve XL. 161-170.

MARJAI M. (1988): Antik mítoszi elemek folklorizálódása a Hortobágyon és környékén - Déri Múzeum Évkönyve 1987. 65: 237-262.

MESTERHÁZY K. (2005): The Hortobágy int he Hungarian conquest period - In: JUHÁSZ I. - Gál E. - Sümegi P. (szerk.): Environmental Archaeology in North-Eastern Hungary Varia Archaeologica Hungarica XIX. Budapest, 387-393.

M├ôDY György: Die siedlungs-und besitzgeschichtliche Übersicht des Gebiets des heutigen Komitats Hajdú-Bihar in den 16-17. Jahrhunderten - A mai Hajdu-Bihar megye területének XVI-XVII. századi birtoklás- és településtörténeti képe. - DMÉ 1971. 65-74 1.

M├ôDY György: Entwurf der Siedlungsgeschichte des heutigen Gebits des Komitats Hajdú-Bihar 13. Jahrhundert - A mai Hajdu Bihar megye területe XIII. századi településtörténetének vázlata - DMÉ 1968. 185-200 1.

MOLNÁR Zsolt (2012a): A Hortobágy pásztorszemmel - Debrecen

MOLNÁR Zsolt (2012b): Hortobágyi pásztorok tájtörténeti és vegetációdinamikai ismeretei - Botanikai Közlemények 99: 103-119.

MOLNÁR Zsolt (2011) Hortobágyi pásztorok hagyományos ökológiai tudása a legeltetésr┼æl, kaszálásról és ennek természetvédelmi vonatkozásai. - Természetvédelmi Közlemények 17: 12-30.

NAGY Jen┼æ: Die Puszta Hortobágy als ein bevozugtes Durchzugs und über winterungs- Gebit in Ungarn - Congres International pour l’Étude et la Protection des Oiseaux - Luxenburg, 1925. 174-185 1.

├ûRSI Zs. - Nagy L. (2002): A Hortobágy környéki pásztorok gyógyító tudománya a XX. század végén - Debrecen

PALÁDI-KOVÁCS A. (1981): ÔÇ×Keleti hozadék” a magyar pásztorkultúrában - In: Dankó Imre (szerk.) Emlékkönyv a Túrkevei Múzeum 30. évfordulójára 109-125.

PALÁDI-KOVÁCS A. (1993): A magyarországi állattartó kultúra korszakai - Kapcsolatok, változások és történeti rétegek a 19. század elejéig - Budapest

PET┼É, Ákos – Barczy, Attila (eds.): Kurgan Studies: An environmental archaeological multiproxy study of burial mounds of the Eurasian steppe zone. 71–133. BAR International series 2238, Oxford: Archaeopress.

PINCZÉS Zoltán: A Hortobágy és a Hajdúhát történeti földrajza a legrégibb kortól a lecsapolásig - Db. 1948.

SCOTT, Peter (1961) The Eye of the Wind

Szabó László 1990 Népi természetismeret. Szolnok Megyei Múzeumi Évkönyv 435-460.

Sümegi, Pál – Szilágyi, Gábor – Gulyás, Sándor – Jakab, Gusztáv – Molnár. Attila 2013. The Late Quaternary Paleoecology and Environmental History of Hortobágy. A Unique Mosaic Alkaline Steppe from the Heart of the Carpathian Basin. In Morales Prieto, M. B. – Traba Diaz, J. (eds.): Steppe Ecosystems. 165–193. Nova Science Publisher, Inc.

SZ┼░CS S. (1946): Pusztai krónika Budapest

ZOLTAI L. (1911): A Hortobágy puszta leírása - Debrecen

ZOLTAI L. (1944): Die Hügelgräber der römischen Kaiserzeit in Hortobágy - S. A. Laureae Aquinceses II. Diss.Pann. Ser. II. 11.

ZSIGMOND Gy┼æz┼æ 1999. Égitest és néphagyomány. Pallas-Akadémia Könyvkiadó, Csíkszereda.

ZSIGMOND Gy┼æz┼æ 1996. Az erdélyi magyarság csillagnévhasználatáról. Acta, a Csíki Székely Múzeum és a Székely Nemzeti Múzeum évkönyve. 215-232

Links to external sites

http://hortobagy.csillagpark.hu/

No multimedia content published

Currently there is no multimedia content published for this case study