Category of Astronomical Heritage: tangible immovable

Tower of the Winds, Greece

Presentation

Geographical position

.bmp)

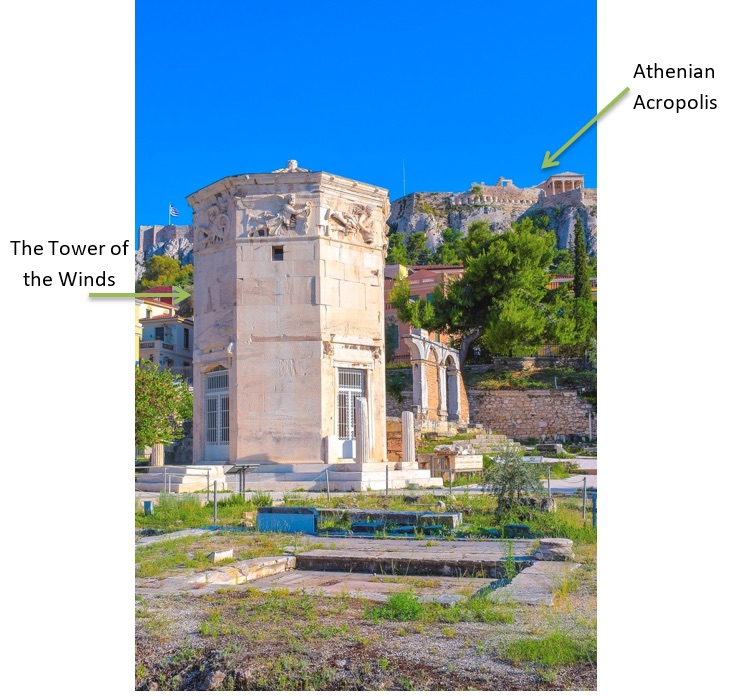

Fig. 1. The Horologion of Andronikos Kyrrhestes on the north side of the foot of the Athenian Acropolis. (see also Fig. 7). Photo © PAPADIMITRIOU

On the north side of the foot of the Athenian Acropolis (roughly 260 m), east of the Roman Agora, Athens, Greece

Location

Latitude 37° 58′ 27″ N, longitude 23° 43′ 37″ E.

Elevation 73 m above mean sea Level.

General description

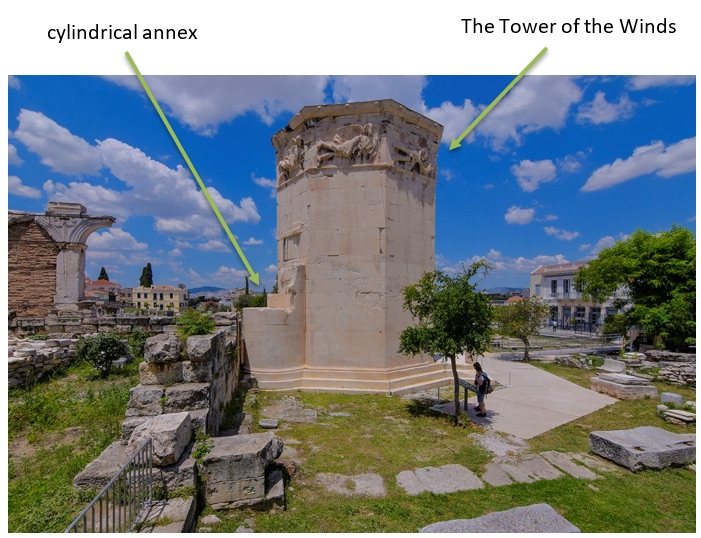

The Horologion of Andronikos Kyrrhestes (official name of the monument), is a structure about 14 m tall and 8 m in diameter. It is an octagonal building, which incorporates a cylindrical structure on the south side. At the top of the eight vertical walls is a vaulted ceiling depicting the sky. Incised lines on the exterior of the eight sides of the edifice show that there once existed this number of sundials. ╬ñhe building has two propyla (gate buildings) and rests on a three-stepped base (crepidoma). It is a particularly remarkable and unusual ancient Greek building, made of Pentelic marble. The name of this, the most important architectural masterpiece of the late Hellenistic period, is derived from the name of its manufacturer, Andronikos Kyrrhestes (Stuart & Revett, 1762; Noble & Price, 1968: 345). It is supposed that this great Greek astronomer, engineer and architect was also the sponsor for the construction of the monument (Wycherley, 1978: 103; Kienast, 2013: 28). The octagonal tower served as an astronomical and weather forecasting station (Vitruvius De Architectura I.6.4, Marcus Terentius Varro Rerum rusticarum libri III, 5, 9-17). The astronomical monument is also called The Tower of the Winds or Aerides (from the Greek word ╬æ╬¡¤ü╬À╬┤╬Á¤é which means winds) or Temple of Aeolus (Aeolus is the ancient Greek god of winds).

In the upper part of its exterior surface is a frieze with eight personified wind deities, one on each of the sides (Fig. 2). The wind deities are: Boreas (N), Kaikias (NE), Apeliotes (E), Eurus (SE), Notus (S), Lips (SW), Zephyrus (W), and Skiron (NW).

Fig. 2. South-western (left) and northern (right) view of the Tower of Winds. In its upper part are depicted the figures of the wind deities Zephyrus (1), Lips (2), Notus (3), Kaikias (4), Boreas (5) and Skiron (6). The deities represent the winds coming from the corresponding direction. Photos © PAPADIMITRIOU

.bmp)

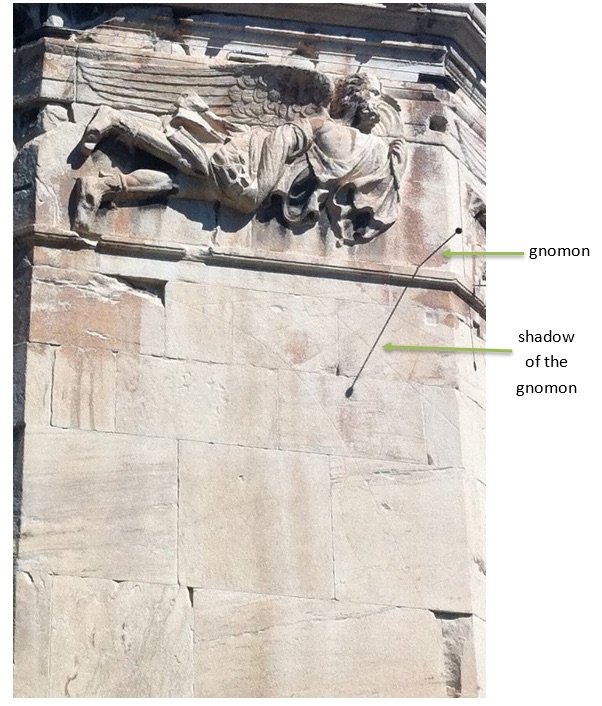

Fig. 3. South-eastern view of the Tower of Winds. The sundial facing south-east is depicted below the corresponding wind deity Eurus. The gnomon and its shadow are also visible. Photo by the authors

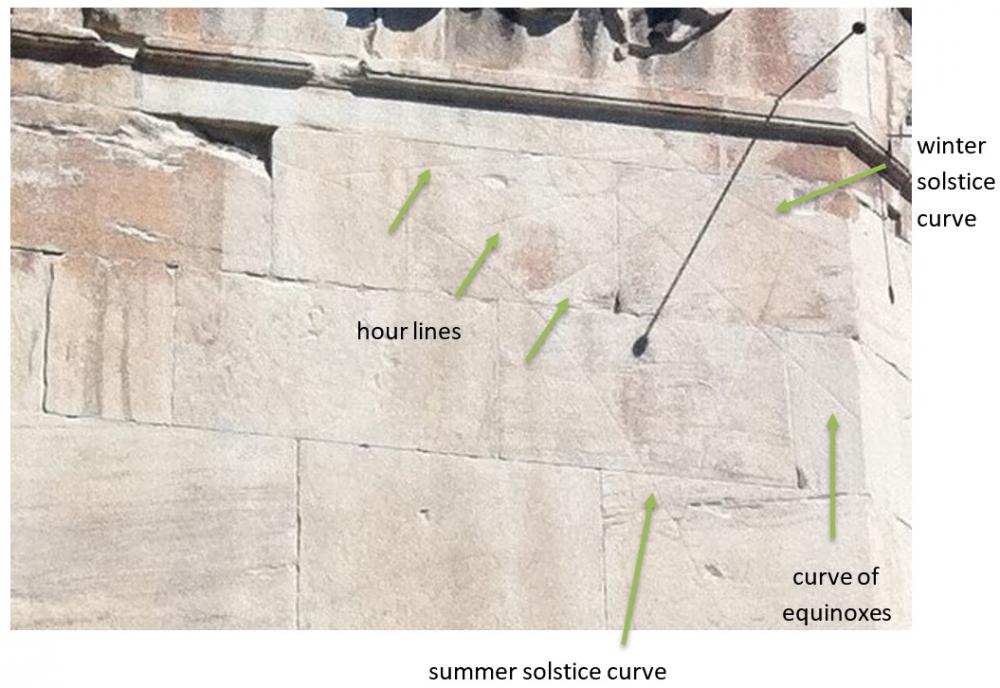

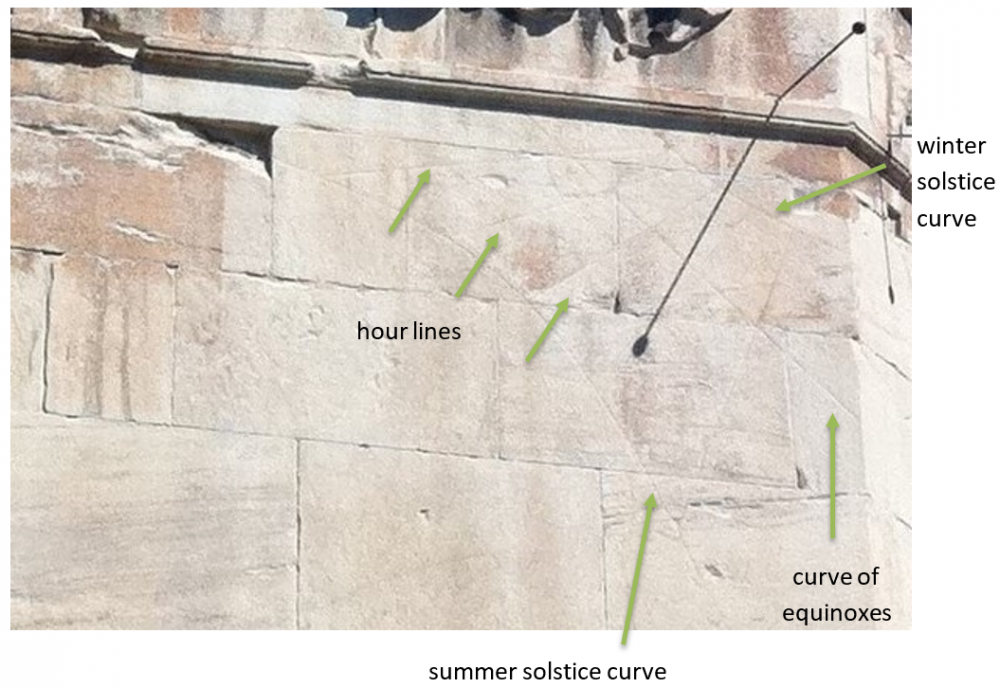

The engraved lines on each of the eight sides (Fig. 3) represent the hour lines and day lines that would have been used to determine the time of day and year respectively from the shadow created by the gnomon on the dial plate. The original gnomons and dial plates have disappeared, but the holes where the gnomons were placed were still obvious, which has enabled them to be replaced by modern replicas (Palaskas, 1845; Bromley & Wright, 1989).

The eight sundials, each facing a different orientation, measured time all day long, throughout the year.

Fig. 4. Views of the exterior (left) and interior (right) of the cylindrical annex from the E and S respectively. The opening in the interior leads to the inside of the octagonal building. Straight channels on the floor carry water to the inner part of the building (see Fig. 5). Photos © PAPADIMITRIOU

A 13.85m-high bronze weather-vane in the form of the Greek god of the sea, Triton, was fixed at the top of the conical roof of the monument (Noble & Price, 1968: 346). Triton was holding his tail in the one hand and a rod in the other (Vitruvius De Architecture Ι.6.4).

The exterior of the octagonal building also features two large openings that serve as entrances to the interior and three much smaller openings serving as windows. The entrances are oriented NE and NW, while the windows— somewhat later interventions (e.g. Robinson, 1943; Noble & Price, 1968)— are to the S, N and W. There is also a small cylindrical annex attached to the main octagonal building on the S side (Fig. 4). On its ruined external surface, there are fragments of engraved lines, showing that there once existed a cylindrical sundial.

There are drawings on the interior walls and residual dark blue pigments on the roof (Kienast, 2013: 25). On the floor there are curved grooves, straight channels and circular holes indicating the former existence of a hydraulic mechanism (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. View of the internal part of the roof (left) and floor (right) of the Tower. Photos by the authors

Brief inventory

The Horologion of Andronikos Kyrrhestes is an astronomical and cultural monument of great importance. According to recent research, it was built around 100 B.C. (Kienast, 2013: 20). The plan view of the octagonal base of the building demonstrates the astronomical use of the monument. The south cylindrical annex indicates the south direction, while the NE and NW entrances indicate the north (Baumeister, 1888: 2112). Given this immediate indication of the north-south direction it is easy for anyone to orient themselves when observing the constellations on a starry night.

Fig. 6. Close-up of part of Fig. 3, showing part of the sundial oriented to the SE. This sundial is appropriate for time measurements in the morning: early on, the gnomon shadow is parallel to the upper edge of the sundial, while at noon it is parallel to the right-hand edge of the sundial. The length of the shadow is short during the winter months (closer to the winter solstice curve); longer during the spring and autumn (closer to the curve for the equinoxes), and much longer during the summer months (closer to summer solstice curve). Thus the sundial functions both as clock and calendar. Photo by the authors

The sundials, below the wind deities, enhance the astronomical use of the monument while at the same time being elements of ancient Greek culture. Sundials were used in the ancient Greek world for measuring time intervals (i.e., they were used as a clock) and for determining the seasons of the year (used as a calendar). Even though the geocentric model was dominant in the Hellenistic period, sundials were accurate astronomical instruments for measuring time. The eight grids of engraved hour lines and day curves are preserved in good condition (Fig. 6). Each sundial has three day curves, one for to the equinoxes and one for each of the solstices.

The sundial engraved on the external surface of the cylindrical annex is oriented to the south and hence could be used for time determination throughout the year. The existence of the other eight sundials enhances the use of the building for astronomical purposes but also emphasizes the importance of time in social life in antiquity. The location of the monument is also crucial: ancient Athenians and other visitors who came to Athens for commercial purposes went to the ancient Roman Agora of Athens, one of the most central and crowded meeting points.

.bmp)

Fig. 7. The Roman Agora in Athens viewed from the SE, showing the cylindrical annex attached to the mail octagonal building of the Tower of the Winds. The arched lintels (see also Fig. 1) connected to the Agoranomeion building complex are visible on the left. Photo © PAPADIMITRIOU

Inside the Tower there was a hydraulic mechanism. Up until the Turkish period, water entered the building under high pressure and was stored in a reservoir in the cylindrical annex. Within 24 hours it was drawn off near the bottom of the reservoir to another tank, which supplied water under constant pressure through a mechanism in the central part of the octagonal building. The curved grooves, straight channels and circular holes that remain in the floor are traces of an ancient water clock/hydraulic mechanism which also represented the motion of the heavenly bodies and the constellations in the sky. Statues of Poseidon, Atlas and Heracles as well as other fountains formed an important operational element of the mechanism. It enabled the ancient Greeks to measure time 24 hours a day (the tank filled and emptied within 24 hours) as well as to predict the movements of the constellations and planets throughout the seasons (Noble & Price, 1968: 350-351). Moreover, the whole surface of the ceiling was covered with the pigment “Egyptian blue” implying that the hydraulic mechanism was an ancient planetarium (Kienast, 2013: 24-25). The figure of Triton on the roof is also of astronomical significance. Triton was a deity of groundwater and is therefore an additional indicator of the existence of the hydraulic mechanism inside the monument (Panou, 2016: 120-121). The water used for the operation of the hydraulic mechanism was sourced from a spring on the northern slope of the Acropolis (see comedy Lysistrata by Aristophanes, line 911) (Fig. 7).

History

According to historical sources, the Horologion of Andronikos served as an astronomical and weather forecasting station (Vitruvius De Architectura I.6.4; Marcus Terentius Varro Rerum rusticarum libri III, 5, 9-17). The Tower was later reused as a baptistery and as a tekke during the Ottoman period. Recent conservation and restoration studies have revealed fragments of wall paintings with Christian content on the interior walls, confirming that the monument was also used for religious purposes in the 13th – 14th centuries. Later, the monument was used as a museum and now it is open to the public.

Cultural and symbolic dimension

The Horologion of Andronikos Kyrrhestes is a masterpiece. Its construction required a knowledge of astronomy, architecture, sculpture, geometry, and instrumentation (sundials, hydraulic mechanism). Ancient Greek observations of the constellations, and the determination of the solstices and equinoxes, are well known. In addition, the Tower served as a meeting point for ancient Athenians.

Authenticity and integrity

The figures of the wind deities are well preserved, and the engraved hour lines and day curves are seen on the eight sundials. However, the original gnomons have been lost, as has the figure of Triton on the roof. The south cylindrical annex is quite ruinous, especially its upper part. Traces of the original cylindrical sundial engraved on the external surface of the annex are still present. In the interior of the Tower there are no traces of the hydraulic mechanism/planetarium apart from the small curved grooves, straight channels and circular holes in the floor. The paintings and drawings on the interior walls are in poor condition. The present-day doors are not the original ones; the original doors were double (Robinson, 1943: 295). As far as the windows are concerned, none of them seems to be original (Noble & Price, 1968: 353), although it is likely that there was always access on the south side into the cylindrical annex (Robinson, 1943: 291).

Documentation and archives

According to Vitruvius (De Architectura I.6.4) Andronikos Kyrrhestes built an octagonal marble tower in Athens. According to this description, a figure representing one of the blowing winds was sculpted on each of the eight façades of the Tower and a Triton wind-like indicator was placed on its roof. Vitruvius speaks highly of Andronikos because the latter was one of those who counted eight winds in antiquity. Marcus Terentius Varro (Rerum Rusticarum libri III, 5, 9-17) compares the Tower to a “Horologium” building somewhere in Italy. The tower was first studied by Stuart and Revett (1762) and during the 19th century the monument was at the forefront of research (Delambre, 1817; Palaskas, 1846; Baumeister, 1888). Studies continued during the 20th century (Drecker, 1925; Robinson, 1943; Noble & Price 1968; Wycherley, 1978; Antonakopoulos & Fragakis, 1969; Gibbs, 1976; Small, 1980; Bromley & Wright, 1989; Rottlander, Heinz & Neumaier, 1989; Huttig, 1998) and remain in progress today (Damianidis, 2011; Kienast, 2013, 2014; Panou, 2016).

Management and use

Present use

The Horologion of Andronikos Kyrrhestes can be visited a part of the archeological open-air site of the Roman Agora. There is an entrance fee. The whole site is officially supervised day and night. Visitors can also view the Tower from outside the surrounding fence.

State of conservation

╬Ön 1976, the Greek Archaeological Service conducted consolidation and conservation work on the roof and the exterior walls of the monument. This work, undertaken to address issues concerning the overall deterioration of the Tower of the Winds, led to extensive conservation work on the interior surfaces of the monument as well, and also to structural reinforcement. Further treatments were implemented between 2014 and 2015 in the context of the project of the National Strategic Reference Framework 2007–2013, “Conservation and Valorization of the Horologion of Andronikos of Kyrrhos, at the archaeological site of the Roman Agora of Athens”. This work was undertaken initially by the ╬æ ╠ü Ephorate of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities and then by the Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens, of the Ministry of Culture and Sports.

Main threats or potential threats

Heavy deposits of aerial pollutants; extensive biodeterioration.

Protection

The conservation and restoration work performed on the monument by the Ephorates of the Greek Ministry of Culture have secured the static reinforcement of the monument, protection from the weather, and accessibility. See “Links to external sites” below.

Context and environment

The Horologion of Andronikos Kyrrhestes itself is largely cleared of vegetation other than grass and small shrubs. Since its former use depended on the area being cleared, the present general appearance of the area is presumably similar to that in antiquity. The immediate surrounding area is also similar to that in antiquity, as the Tower was built within the Roman Agora. There are modern houses in the vicinity.

Archaeological / historical / heritage research

Historical sources and archaeological evidence affirm the use of the Horologion of Andronikos Kyrrhestes for the measurement of time (hourly and over the course of the year), counting sunny days, and the observation of planetary orbits and constellations, as well as of wind direction.

Management, interpretation and outreach

In common with all significant Greek archaeological sites, the Horologion of Andronikos Kyrrhestes is the property of the state, and in 2015 major works of conservation, restoration and study were completed by Ministry of Culture and Sports – Ephorate of Antiquities of Athens, Greece, which also has responsibility for the area.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles)

Antonakopoulos, G. and Frangakis C. (1969). The Andronikos solar clock in Athens (╬ñ¤îß╝É╬¢ ß╝ê╬©╬«╬¢α╬╣¤é ß╝í╬╗╬╣α╬║¤î╬¢ ߢí¤ü╬┐╬╗¤î╬│╬╣╬┐╬¢ ¤ä╬┐ß┐ª ß╝ê╬¢╬┤¤ü¤î╬¢╬╣╬║╬┐¤à). Archaeological Annals of Athens, 2(3), 416–422 (in Greek).

Baumeister, A. (1888). Denkmäler des klassischen Altertums. Leipzig. 2112, s.v. Windeturm.

Bromley, A.G. and Wright, M.T. (1989). The Temporal Hours of the Tower of the Winds at Athens. Technical Report 365. University of Sydney: Basser Department of Computer Science.

Damianidis,K.A. (2011). Roman ship graffiti in the Tower of the Winds in Athens. Archäologisches Korrespondenzblatt, 41, 85–99.

Delambre, ╬£. (1817). L’ Histoire de l’astronomie ancienne, Paris, pp. 487–504 and plates 11 and 12. (Quoted by Robert R. Newton [1979] in The Moon’s Acceleration and Its Physical Origins [MAPO]. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, Vol. I.)

Drecker, J. (1925). Die Theorie der Sonnenuhren. In Bassermann-Jordan (ed.), Geschichte der Zeitmessung und der Uhren, Gruyter-Velag, Berlin/Leipzig.

Gibbs, S. (1976). Greek and Roman Sundials. Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

Hüttig, M. (1998). Analysis of the sundials on the Tower of the Winds, Athens: possible parameters used in construction. British Sundial Society Bulletin, 98(3), 12–15.

Kienast, J.╬ù. (2013). The Tower of the Winds in Athens. The Australian Archaeological Institute at Athens (AAIA) Bulletin. 9, 20–29.

Kienast, J.╬ù. (2014). Der Turm der Winde in Athen; mit Beiträgen von Pavlina Karanastasi zu den Reliefdarstellungen der Winde und Karlheinz Schaldach zu den Sonnenuhren, Reichert, Wiesbaden.

Palaskas, L. (1846). Mémoire présenté ├á la Société Archéologique d’ Athènes. Resumé des actes de la société archeologique d’ Athenes, 247–286.

Panou, E. (2016) Time measurements and related astronomical instruments in Greek antiquity: The Horologion of Andronikos Kyrrhestes (Tower of Winds) and other ancient sundials. Proposals and applications of educational activities for teaching related terms in education. Ph.D. Dissertation, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Physics Department, Greece (in Greek).

Noble, N.J. and Solla Price, D.J. (1968). The Water Clock in the Tower of the Winds. American Journal of Archaeology, 72(4), 345–355 (plates 111-118 with photographs).

Robinson, H. (1943). The Tower of Winds and the Roman Market-Place. American Journal of Archaeology. Vol. 47, pp. 291-305

Rottländer, R.C.A., Heinz, W. and Neumaier, W. (1989). Untersuchungen am Turm der Winde in Athen. ├ûsterreichisches Archäologisches Institut, 59, 52–92.

Small, D.B. (1980). A Proposal for the reuse of the Tower of the Winds. American Journal of Archaeology, 84, 96–99.

Stuart, J. and Revett, N. (1762). The Antiquities of Athens I. London, pp. 13–25 (pls I–XIX).

Varro (1934). Rerum rusticarum libri III, ed. W. Davis. London: Hooper.

Vitruvius (1914). De Architectura, trans. M. H. Morgan. London University Press.

Wycherley, R.E. (1978). The Stones of Athens. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Links to external sites

“Horologion of Andronikos Kyrristos”, Odysseus portal, Ministry of Culture and Sports

No multimedia content published

Currently there is no multimedia content published for this case study