Category of Astronomical Heritage: dark skies

Eastern Alpine and Großmugl starlight areas (multiple locations): East Alpine Starlight Reserve

Identification of the property

Country/State Party

Austria

State/Province/Region

Lower Austria, Upper Austria and Styria

Name

Eastern Alpine Starlight Reserve

(Part of Eastern Alpine and Großmugl starlight areas)

Geographical co-ordinates and/or UTM

Elliptical area including Dürrenstein Wilderness Area, Gesäuse National Park and Kalkalpen National Park:

Long axis (approx. W-E): 47° 11′ N, 13° 50′ E to 47° 58′ N, 16° 55′ E

Short axis (approx. N-S): 47° 50′ N, 14° 27′ E to 47° 18′ N, 14° 52′ E

Alternative elliptical area additionally including Nockberge National Park (Carinthia):

Long axis (approx. W-E): 46° 52′ N, 13° 35′ E to 47° 58′ N, 16° 55′ E

Short axis (approx. N-S): 47° 50′ N, 14° 27′ E to 47° 18′ N, 14° 52′ E

Maps and plans,

showing boundaries of property and buffer zone

See Eastern Alpine and Großmugl starlight areas

Area of property and buffer zone

Core area:

Total 34,304 ha, comprising

- 20,850 ha (Kalkapen National Park),

- 11,054 ha (Gesäuse National Park), and

- 3,500 ha (Dürrenstein Wilderness Area).

Buffer zone:

~ 19,000 km² (~ 100 × 60 km).

Alternative including Nockberge National Park: ~ 41,000 km² (~ 220 × 60 km).

Description

Description of the property

The iconic landscape of the Alpine range together with its comparatively less known, very wide eastern third form a ~1000 km² area containing natural skies above a unique mountain landscape.

The core-zone of the proposed Eastern Alpine Starlight Reserve is comprised of three of the most secluded areas in the widest part of the Alpine arc, each of which is an IUCN-recognised Austrian nature conservation area. These are:

- The Wildnisgebiet Dürrenstein (Dürrenstein Wilderness Area) in Lower Austria (IUCN category I), of which the Urwald Rothwald (Rothwald primary forest) (IUCN category Ia) is a component;

- The Nationalpark Kalkalpen (Kalkalpen National Park) in Upper Austria (IUCN category II); and

- The Nationalpark Gesäuse (Gesäuse National Park) in Styria (IUCN category II).

Together they span a ’starlight triangle‘ which is readily visible as a central European dark spot on satellite imagery.

History and development

This remote area, where the borders of three provinces meet, has long proved difficult for human access because its mountains and basins are protected by long and narrow access gorges. It was overlooked by the Alpine tourism that began in the Western Alps in the 19th century and by the hydroelectric power development of the 20th century. The Kalkalpen and Gesäuse National Parks and the Dürrenstein Wilderness Area were declared in the 1990s and early 2000s, respectively, to protect against more recent development pressures.

Within the Kalkalpen National Park area, stone tools (found in the Ramesch cave) show that hunting practices extended as far back as 65,000 BCE, and bone-tools have also been found (e.g. in Losenstein) dating from 18,000-10,000 BCE. From the Late Neolithic onwards, pastoral farming on seasonal high-elevation meadow meadows—’Alms‘ or ’Alps‘—became essential in order to sustain the human presence in this area. During the Bronze Age, cattle were driven into the woods for grazing in the Dürrenstein area and pasturage on the high-elevation meadows of the Dürrenstein commenced in the first century BCE. The first written documents relating to Alm-management date back to the 16th century for the Schaumbergalm and Jörgl-Alm, and to 1647 for the Annerl-Alm in the Kalkalpen National Park.

In all three core areas, mining activities drove humans into the most secluded valleys. Copper melting spots are documented in the Gesäuse from 1800 BCE. Metal tools found within the Kalkalpen National Park area demonstrate the use of the natural north-south passes through the Alps by about 1000 BCE. Iron production drove humans towards the most inaccessible woodlands, the limit being set by their ability to extract it using the waterways. Iron-Age activities in the Alps are recognised in the ’Hallstatt-Dachstein/Salzkammergut Cultural Landscape‘ World Heritage Site (whc.unesco.org/en/list/806): ferrum noricum (Noric steel) was exploited through antiquity.

Population pressure reached a first peak with medieval deforestation, which also progressed deeply into the valleys. The earliest written records, from the monastic period, show that in 1330 just 2700 ha of primary forest remained in the Dürrenstein Wilderness Area (the Habsburgs’ endowment to the Carthusians (Karthäuser)), less than 10% of the stipulated area in the modern communities of Gaming, Scheibbs, St. Anton and Lunz am See.

The ’Rothwald‘ primary forest in the Dürrenstein Wilderness was protected into the 19th century by an enduring gridlock between timber harvesting by the Carthusians in Gaming and the ’competing‘ Benedictine Monastery in neighboring Admont, which had been founded in 1074 by the Archbishop of Salzburg at the western entrance of the Gesäuse valley. (Admont Abbey, which includes the largest monastic library hall in the world, is at the centre of the Eastern Alps and forms the core of the settlements around the Gesäuse National Park.) While the Carthusians at Gaming owned the land use rights, the limited capacity of the waterways would, in practice, only permit the transportation of timber across land owned by the Benedictians in Admont. Nonetheless, a settlement between the monasteries of Admont and Gaming in 1689 did allow further exploitation of wood driven by the huge energy demand of the nearby iron production in the ’Eisenwurzen‘ (literally, ’root of iron‘) area. It is estimated that 25% of Europe’s iron production at the time came from that region. The Carthausian monastery was secularized in 1782 by a decree of Emperor Josef II. The Rothwald primary forest was reduced to 1520 ha under the following imperial state ownership. Private ownership commenced in 1825, reducing the Rothwald by a further 950 ha.

By 1750 the wood shortage had become so acute that woodcutting started in the most remote valleys. This happened as late as 1765 in the Jörglgraben, now part of the Kalkalpen National Park. Trees there were only harvested once in history and it is suspected that patches of primary forest survived into the present between the ’secondary‘ forest. In 2000 a total of 37 ha of primary forest could be identified.

With the energy-hungry industrialization, wood was harvested on a large scale, driven in particular by the relative proximity, downstream, of the rapidly growing imperial capital, Vienna, and its demand for firewood. Today, Vienna still takes advantage of this proximity: its water supply comes from the Eastern Alpine mountains with two of the three main source areas overlapping with the cores of the starlight reserve.

Just before industry moved to fossil fuel in the 20th century, a new wave of timber exploitation reached the Alps, halted only by inaccessibility and a water system that could not be controlled by late 19th century technology. The ’Aktiengesellschaft für Forstindustrie‘ (a stock company) acquired a large fraction of the forests in the Dürrenstein area in 1865. It introduced log rafting on the Ybbs river to feed a steam-driven sawmill on the Danube. Massive modifications of the Ybbs river were undertaken in order to allow large-scale timber transportation, which left a devastated landscape plagued by landslides and flooding when the company went into bankrupcy in 1875.

These activities overlapped with the opening of the first large-scale conservation area, the Yellowstone National Park, in 1872. After the bankruptcy large pieces of land, including 420 ha of primary forest, remained and were purchased by Albert Rothschild, who already had held a share of the Forstindutrie AG. Now the sole owner, he realized the value of the untouched wilderness and protected the remaining Rothwald primary forest. It is due to him that the Rothwald survived against both the pressures of technology — which now provided possibilities for timber extraction without using the waterways — and the pressures to improve nature as vocalized by the Academia of the time. (They used the primary forest for teaching, as an example of the chaos and decay that will occur without human intervention and improvement.)

In 1935, parts of the forest — which now constitutes some of the Western areas of the Dürrenstein Wilderness — were sold following the ’Creditanstalt Crisis‘, one of the triggers of the global economic crisis. The remaining properties were appropriated in 1938 after the ’Anschluß‘ of Austria to Nazi Germany. Since the Rothschild family had taken over, only 20 ha of primary forest had been lost, after wind damage. The ecological importance of deadwood was not recognized at the time and thus the area had been cleaned out. This also led to the realization that the untouched forest could not resist all forces of nature.

During the Second World War the primary forest was declared a nature conservation area, with somewhat arbitrary zoning. In 1946-47 the properties were returned to the Rothschild family but some parts in the west were traded by Louis Rothschild to what is now the Second Austrian Republic in exchange for pension duties. In 1988, a modern zoning concept was implemented after the inclusion of the Rothwald II area.

The Dürrenstein Wilderness area was founded in 1997, supported by a European Union nature conservation project. Nature conservation is handled by provincial governments, and in May 2001 the government of the State of Lower Austria finalized legal protection. Recognition by the IUCN as a Category Ia Protected Area following two years later.

The Kalkalpen National Park reached its present area after extensions in 2001 and 2003.

In addition to the areas in the Forstverwaltung Langau that are still owned by the Rothschild family, Austrian National Forestry properties on the south-west slopes of the Dürrenstein mountain-massif were added in 2002, yielding a total of 2,400 ha (24 km²) in 2013. Today’s size of 3,500 ha was reached in 2014 by including partially protected neighboring areas and placing the whole Wilderness Area under the legal umbrella necessary for the IUCN category I by a new decision of the provincial government.

This section is prepared on the basis, and largely following the history chapter, of the Dürrenstein Wildernis book by the Reserve’s present director, Christoph Leditznig, with kind permission of the author. Information on the Kalkalpen National Park is mostly based on sources from the Park Administration with kind permission of its director Erich Mayrhofer.

Justification for inscription

Comparative analysis

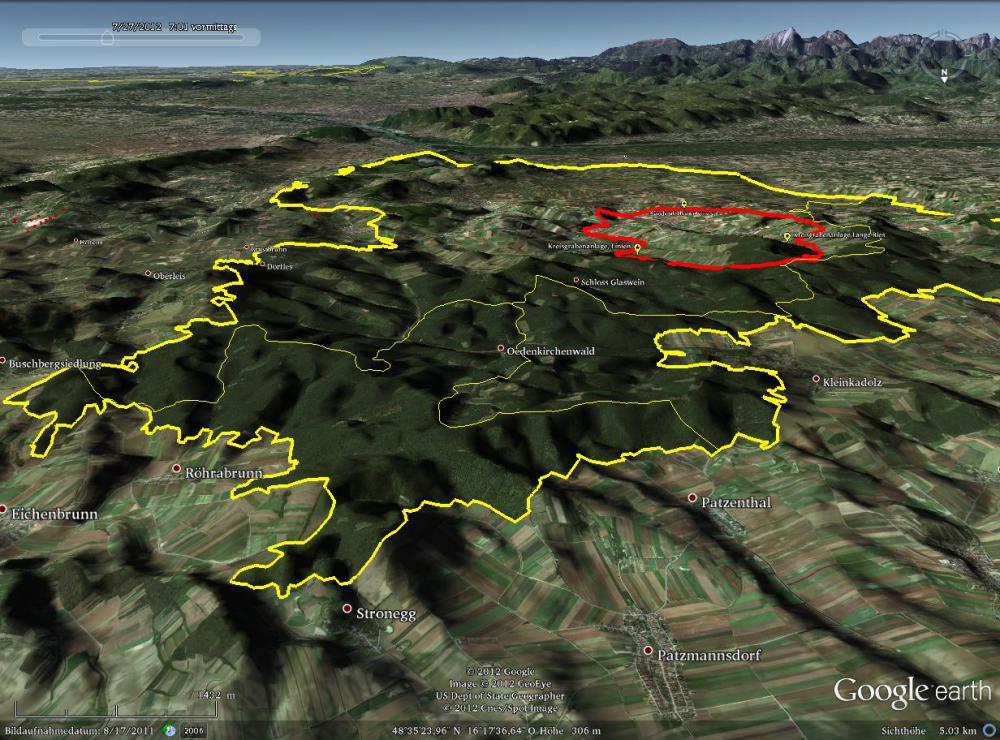

Satellite data show clearly that, at least as far as light-sources on the ground are concerned, the Alpine Arc is the largest dark spot in central Europe (see Eastern Alpine and Großmugl starlight areas Fig. 1). Along this arc, the Eastern Alpine location is optimal because the effects of scattered light on sky quality are minimized: the light-intense regions of northern Italy and the strongly developed western Alps are at the greatest distance that can be achieved within the mountain range.

The extent to which light is reduced depends upon the comparative height and width of the mountain range. A 1000m-height difference reduces a large fraction of the aerosol scattering, and the skies certainly benefit from additional height. That is also true for the light-blocking effect where a mountain system acts as a natural baffle. For that, the width of the mountain range is important. That is a particularity of the Alps. It is shared with the Rocky Mountains, the Northern Andes and the Himalayas.

An additional factor in the Alps is the absence of high-altitude plains that attract human settlement. This reduces light pollution pressure compared to, say, Salt Lake City in the Rocky Mountains. A similar but narrower mountain chain can certainly protect skies of similar quality in less populated areas than Europe, the exceptional sky quality of the Aoraki-Mackenzie region of New Zealand (see case study on this portal), adjacent to the Southern Alps, being a case in point. The Natural Bridges Dark Sky Park located on the high altitude Colorado plateau is also sparsely populated. Sample measurements by the author showed that the sky quality there is broadly indistinguishable from that in the Eastern Alpine Starlight Reserve. However, at this very high level of sky quality, natural seasonal variations in the appearance of the Milky Way, airglow, and extinction (due, for example, to aerosols above the desert) are major factors and many measurements at both sites would be required for a meaningful comparison.

In any case, a comparison based on sky quality alone is insufficient because the night sky—and the twilight—varies with latitude. These latitudinal variations are significant and produce skies of very different character, the most commonly appreciated distinction being that between the Northern and Southern sky.

Nightscapes are as rich and diverse as the landscapes with which they are associated, and a classification of sky-landscape systems is surely necessary for a complete inventory of unique sky-heritage. A first step could be to distinguish, for example, high-elevation plains with open skies from summit-gorge areas such as canyon-lands, or places where parts of the horizon is formed by an ocean. It is evident that more specific comparisons are possible. The value of landscapes under the Moon or seen by the light of a starry night sky is becoming more commonly appreciated.

The latitude of the Alps (both Northern and Southern) together with their height produces a relatively rare feature: icy or snowy summits all year round, which create a particular impression when starlight or moonlight shines on the white ground, maximizing the contrast.

State of conservation and factors affecting the property

Present state of conservation

The Dürrenstein Wilderness Area contains the largest contiguous stretch of primary forest in the Alpine arc. This has not been cultivated or managed since the last Ice Age and thus supports a variety of Alpine flora and fauna (for more detail see www.wildnisgebiet.at). Following IUCN guidelines it is divided into the following zones (see www.wildnisgebiet.at/en/portrait/zoning/):

- A natural zone where no measures are implemented except for the regulation of game. Visitors may enter certain parts of this zone when participating in guided tours. This covers approximately 88% of the Wilderness Area.

- A natural zone with woodland management. For a limited period of time, secondary spruce forests are being transformed into mixed forests with a high proportion of deciduous trees. This comprises less than 5% of the Wilderness Area.

- An Alpine pasture management zone where cattle grazing is permitted to the same extent as prior to the zoning. This maintains the grasslands which provide habitats for a large number of rare species of plants and insects, as well as for black grouse and ptarmigan. This covers about 7% of the Wilderness area.

- A wildlife management zone overlapping the zones above, where the number of deer and other ungulates is regulated in order to protect the balance between forest and game. This comprises about 25% of the Wilderness Area.

The Kalkapen National Park contains Reichraminger Hintergebirge, part of one of the most unspoiled wooded areas in Austria. So far this mountain forest has not been affected and destroyed by public transportation routes or settlements.

The Gesäuse National Park embraces two limestone massifs: the Buchsteinmassiv and the Hochtorgruppe. It is largely untouched and has high biodiversity.

The sky quality in all three areas is exceptional. Light levels generally compare with those for natural skies, both by day and by night. The darkest night skies (Fig. 1) are the most frequent and occur under prevailing weather conditions—not just in exceptional circumstances. The brightness of the sky is comparable to the one of the best astronomical sites of the world—though of course not with the same number of clear nights.

These pristine skies above pristine Alpine mountain landscapes sustain biodiversity by providing habitats with natural conditions both by day and by night (Fig. 2). They support the nocturnal majority as well as numerous daytime-active rare species and their habitats (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1: Gegenschein in the zodical band (centre) in the Eastern Alpine Starlight Reserve above the Kalkalpen National park as seen from the ’Hohe Dirn‘ (1000m). The Milky Way is rising on the left. Photograph: R. Dobesberger, Sternfreunde Steyr

Fig. 2: The moon above Gesäuse National Park, showing the point where the River Enns emerges from the canyon (partly obscured by patches of mist) on the left. The bright moonlight brings out colours in this image that are visible in a moderated way to the human eye in mesopic mode. Note the stars in the blue sky. Photograph: Norbert Fiala (kuffner-sternwarte.at)

Fig. 3: The boreal owl (aegolius funereus, a precious nocturnal species) looking north together with the sky above its frequent hunting and nesting grounds in the Dürrenstein Wilderness Area. Image: P. Buchner, www.birdlife.at (owl), G. Wuchterl (stars), K. Einhorn (montage)

Factors affecting the property

Developmental pressures

The population of the area is shrinking and skiing activities in neighbouring regions have declined, and will decline further, owing to climate change. Thus, fragmentation by urban development is not an issue in this area.

Environmental pressures

There could possibly be an increase in light-pollution from the growth of cities more than 100 km away.

Visitor/tourism pressures

Skiing and other Alpine outdoor activities.

No. of inhabitants

None in the 3 IUCN-recognised areas; an estimated 100,000 in the buffer-zone.

Protection and management

Ownership

There is mixed ownership: a large proportion is state-owned land managed by the Austrian Federal Forest Administration (Österreichische Bundesforste). For example, 88% of the Kalkapen National Park is state-owned, with 11% in under private ownership and 1% municipal property.

Protective designation

The natural heritage is protected by federal National Park law and by state nature protection law. The area is a Starlight Natural Site in the context of the Starlight Reserve Document.

Means of implementing protective measures

A set of nature-protection regulations recognized by the IUCN is in place for the conservation of the three components of the core zone. State light-pollution laws, with sections on conservation areas, are in preparation. The spread of national light-pollution laws, already existing in the Czech Republic, Slovenia and many provinces of Italy, could counteract the threat of light-spill from the growth of distant cities.

Existing plans

It is planned to increase the existing night-oriented activities, managed by the park administrations in cooperation with astronomical organizations such as the Kuffner Observatory and Sternfreunde Steyr.

Sources of expertise and training

Sources of astronomical expertise and training include

- Institute for Astronomy, University of Vienna (didactics of astronomy education for teachers);

- the Kuffner-Sternwarte Society (amateur and professional astronomers and physicists);

- the Linzer Astronomische Gemeinschaft;

- Sternfreunde Steyr; and

- Hochbärneck Observatory.

National Park institutions provide expertise and training relating to other issues in the Eastern Alpine Starlight Reserve.

Visitor facilities and infrastructure

The National Parks and Wilderness Area provide visitor centres and infrastructure. In the conservation zone of the primary forest of the Dürrenstein Wilderness area, human access is only possible under exceptional circumstances.

Presentation and promotion policies

The National Park and Wilderness Area have already included night-time activities in their programmes.

Monitoring

Indicators for measuring state of conservation

The key indicators are:

- Illumination levels and total radiation.

- Complementary background sky brightness or near zenithal average sky brightness (SQM-measurements) and all-sky brightness distribution.

- An air-quality related value (visibility versus haze):

- *total aerosol optical depth

- *mass fraction of particulate matter with respect to an upper size limit specified by ┬Ám

- *ozone (health)

Continuous monitoring of the sky quality in the proposed reserve is carried out by the Kuffner-Sternwarte Society in collaboration with the Dürrenstein Wilderness area and the Sternfreunde Steyr.

Documentation

Photos and other AV materials

Extensive multilingual documentation is available on-line for the Dürrenstein Wilderness Area, Gesäuse National Park and Kalkalpen National Park.

Bibliography

For an extensive bibliography on the Eastern Alpine Starlight Reserve area see the park websites:

No multimedia content published

Currently there is no multimedia content published for this case study