Category of Astronomical Heritage: tangible immovable

Risco Caído and the sacred mountains of Gran Canaria, Spain

Identification of the property

Country/State Party

Spain

State/Province/Region

Gran Canaria Island, Canary Islands

Geographical Region: Africa

Biogeographic region: Macaronesia

Name

Risco Caído and the Sacred Mountains of Gran Canaria

Geographical co-ordinates and/or UTM

Risco Caído—astronomical sanctuary

- Latitude 28° 2′ 37″ N, longitude 15° 39′ 40″ W

- UTM Zone 28N: 435023 3102210

- Elevation 1044 m

Geographical centre of the sacred landscape (Roque Bentayga)

- Latitude 27° 59′ 7″ N, longitude 15° 38′ 15″ W

- UTM Zone 28N: 437310 3095735

- Elevation 1412m

Maps and plans,

showing boundaries of property and buffer zone

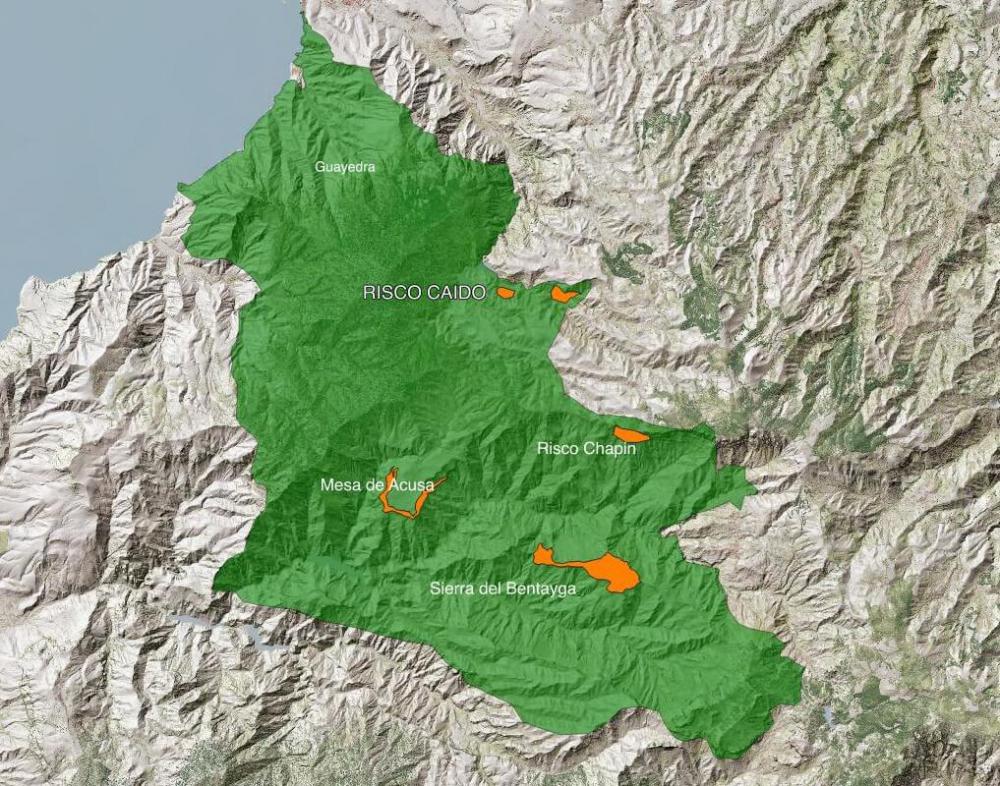

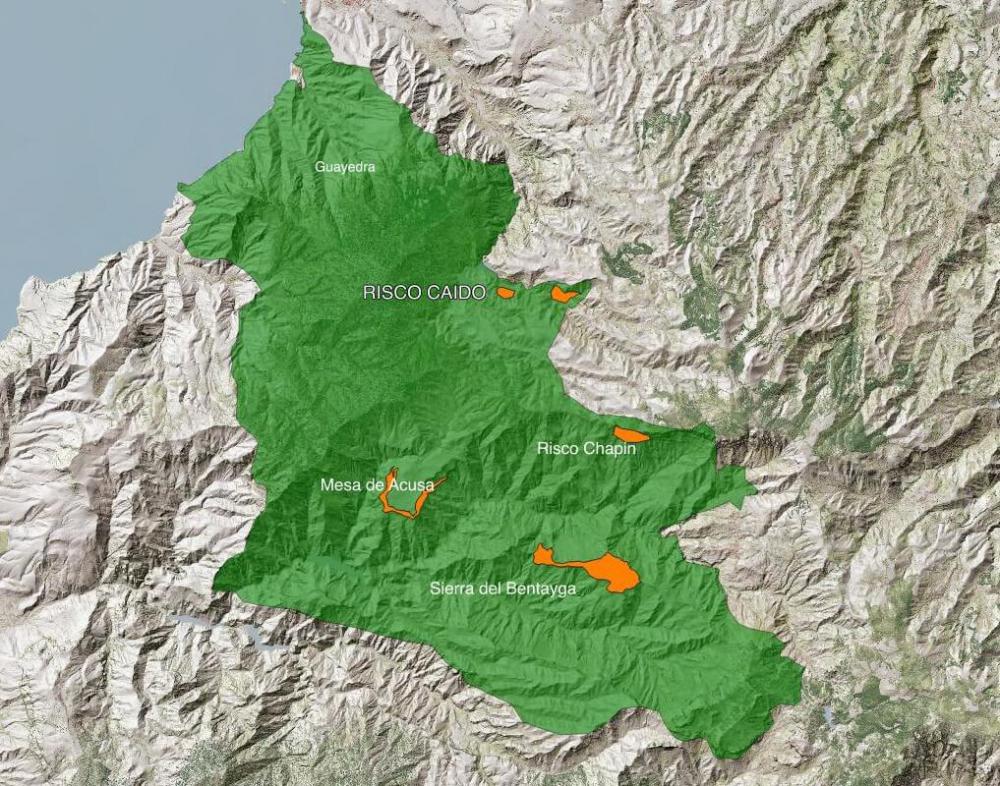

Fig. 1. Location of the sacred mountains area of the original inhabitants of the Canary Islands. Photograph © Cabildo de Gran Canaria

Fig. 2. Location of the sites of special archaeoastronomical and symbolic interest in the sacred mountain area. Photograph © Cabildo de Gran Canaria

Fig. 3. Zoning boundaries and core areas. Photograph © Cabildo de Gran Canaria

Fig. 4. The sacred area, the sites of archaeoastronomical interest and the Gran Canaria Biosphere Reserve zoning. The entire area is located within a biosphere reserve that enjoys both cultural and environmental protection. Photograph © Cabildo de Gran Canaria

Area of property and buffer zone

9872 ha

Description

Description of the property

The sacred site is located to the north-west of the island of Gran Canaria in a region extending across the municipalities of Artenara, Agaete and Tejeda, which is presided over by the imposing volcanic crater “Caldera de Tejeda”. The area includes the Caldera de Tejeda crater and a substantial part of the Tamadaba Nature Reserve (see Fig. 2). Located within the Tamadaba reserve are “Parajes de Tirma”, another of the sacred sites of the ancient inhabitants of the island, and Guayedra, the place of residence of Fernando de Guanarteme, the last of the island’s kings.

This complex of archaeological sites, landscapes and natural phenomena binds together what was the sacred homeland of one of the most extraordinary and least known island cultures on the planet. This culture, now lost, evolved in total isolation over more than fifteen hundred years.

Fig. 5. General view of Caldera de Tejeda, the sacred site of the ancient islanders. Photograph © Cabildo de Gran Canaria

The sacred site of Caldera de Tejeda reveals the existence of multiple structures built by the original inhabitants of Gran Canaria, the main walls of which are aligned with the rising and setting sun, particularly at the Summer Solstice and the Equinoxes (Belmonte et al., 1995). In many cases, these are architectural structures, mainly artificial caves, used for rituals and as astronomical markers to control the passage of time. Such an abundance of astronomically aligned sites can only be explained by the need these islanders had to accurately control the passage of time and to know the changing seasons. The very survival of this island culture—caught between the sea and the sky—depended upon it.

Environment

This is a place that brings together, in perfect harmony, exceptional cultural values and natural surroundings with an incredibly rich abundance of landscapes, flora and fauna.

Caldera de Tejeda is a unique geological phenomenon. It is a unique example of a pit crater formed by the collapsed magma chamber of an ancient salic volcanic structure that emerged some 14 million years ago. This area is included on the list of special geodiversity sites of the Geosites Programme, supported by UNESCO (Carcavilla Urquí & Palacio Suárez-Valgrande, 2011). The list includes two natural monuments with astronomical significance that are worthy of special mention: Roque Bentayga and Roque Nublo.

Part of the region, particularly Tamadaba, is considered one of the biodiversity hot-spots of the Canaries (Martín, 2010). The latest studies carried out by Viera y Clavijo Botanic Gardens record a wealth of flora in the area with more than 100 endemic species per square kilometre, particularly along the boundaries of the Tamadaba pine groves and Finca de Tirma, which is a natural legacy of world interest. Thus, several of the landscapes in this area can be considered true relics of the natural habitat of the early settlers of the Canary Islands.

Tangible heritage

Tangible manifestations of archaeological and archaeoastronomical importance, nowadays referred to as “star sites”, are grouped into four main areas: the Risco Chapín sanctuary, Sierra del Bentayga, Mesa de Acusa and Almogarén de Risco Caído.

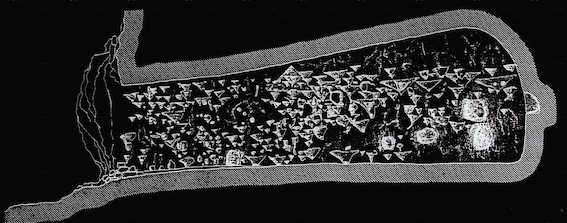

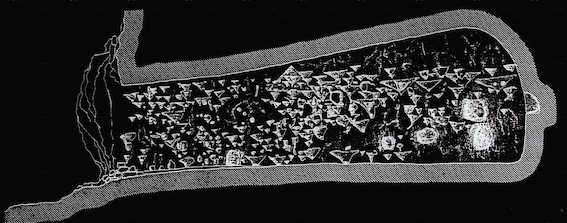

Fig. 6. Section of the Candiles cave and reproduction of the cup marks and pubic carvings. The floor is perfectly aligned with the Roque Bentayga astronomical sanctuary-marker. Photograph © Julio Cuenca

On the vertical walls to the north of Caldera de Tejeda crater is the Risco Chapín sanctuary, an area that incorporates the cave sites of Cueva de Candiles, Cuevas de Caballero and Cueva del Cagarrutal. This is a complex of hollowed-out caves with unique carvings on the inside walls, with a proliferation of pubic triangles, bas relief carvings, and cupules or cup marks carved into the floor and walls. The Candiles caves contain more than 350 carvings lining the interior walls of the artificial chamber that houses the largest number of representations of this pubic ideogram in the world (Cuenca Sanabria, 1994).

Outside these sacred mountain sites, there are very few sites on the island with these types of pubic carvings that relate to fecundity and fertility (López Peña et al., 2004). Astronomical orientation and vocation is evident in the caves of Cuevas de Caballeros and Cueva de Candiles, as is the symbolic relationship and alignment with the Roque Bentayga and Roque Nublo.

Fig. 7. The Bentayga Almogarén temple. An observer situated at the cupule and looking up at the indentation in the rock would witness the setting equinoctial sun creating an interplay of light and shade in the form of a V over the almogarén. Bearing in mind that the position of the setting sun varies quite considerably (by almost 24′) each day as it crosses the celestial equator and that the size of the indentation from the point of view of the observer is very similar to the diameter of the sun (30′) it can be affirmed that observation of the phenomenon would allow the date of the equinox to be accurately calculated within a range of approximately one day. Photograph © PROPAC

Fig. 8. Sunrise at the equinox from the almogarén at Roque Bentayga. Photograph © Arqueoastronomía Canaria

The Sierra del Bentayga archaeological complex includes Roque de Cuevas del Rey and Roque Bentayga. The former is unique in that it houses a dense and unique complex of caves that were used as a collective granary. Cueva del Rey is located here. Adorned with its unusual pictorial motifs this cave is one of the most significant examples of a cave sanctuary in the Canary Islands. The latter is the true epicentre of the symbolism and cosmology of the ancient Canary Islanders. Roque Bentayga was used as an impenetrable fortress until it was finally overthrown and taken by the Spanish troops at the end of the 15th Century. This is an extraordinarily rich archaeological site in which are found ancient walls, caves with cave art, alphabetical inscriptions (Cuenca Sanabria, 1994; 1995) and the almogarén or temple of Bentayga (see Figs. 7 and 8). The almogarén is designed and positioned in such a way that it has an astonishing natural alignment with Roque Nublo suggesting its astronomical use to mark the equinoxes, thus providing exceptional archaeological evidence of what was related in the Chronicles of the Conquest about the peculiar calendar used by the native peoples (Belmonte & Hoskin, 2002).

Fig. 9. Above the cliff edges of the Mesa de Acusa plateau is a unique cave-dwelling settlement, part of which is still inhabited to this day. Photograph © PROPAC

The Mesa de Acusa plateau (see Fig. 9), which in itself constitutes an impressive geological monument, was one of the largest and most spectacular fortified cave dwellings of these early settlers. This impressive settlement borders the rocky escarpments of the large fertile plain on top of the plateau. This complex of rock caves adorned in places with beautiful pictograms and used as dwellings, granaries, places of worship and burial, in conjunction with the agricultural area on top of the plateau, comprises a cultural landscape that ranks amongst those most suggestive of a prehistoric habitat that has survived up to the present day. Until recent times this ancient settlement known as “cuevas de los antiguos” was more densely populated than some of the bigger villages of the north of the island (Cuenca Sanabria, 1996).

Fig. 10. Interior of the almogarén at Risco Caído, a wonderful example of the architectural and astronomical knowledge of the early settlers on the island. Image taken with a fish-eye lens. Photograph © Julio Cuenca

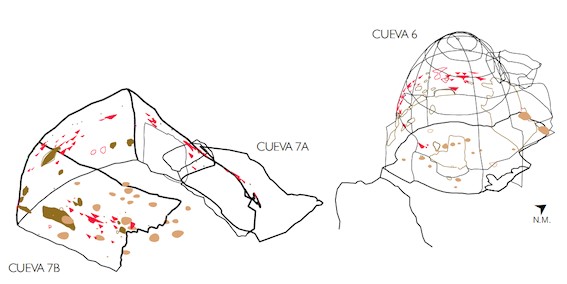

Finally, on the left-hand side of Barranco Hondo ravine is the ancient cave settlement of Risco Caído, located in an area rich in paleontological remains. The settlement is formed of some twenty artificial caves, two of which are worthy of special note: caves C6 and C7. Situated to the north of the settlement, these caves, probably the oldest in the area, house what was a mountain sanctuary for the early inhabitants of the island in ancient times (see Fig. 10).

Current archaeological research seems to suggest that this “lost temple” of the ancient settlement was also used as an ingenious and precise astronomical marker that signalled the arrival of the equinoxes and the summer solstice as the rays of the rising sun entered the interior of the temple. The winter solstice was marked by the entry of the light of the full moon (Cuenca Sanabria et al., 2008).

Fig. 11. Snapshot of one of the moments in the narrative on the rays of sunlight that are projected onto the wall of the cave sanctuary of Risco Caído. Photograph © Julio Cuenca

Yet more amazing is that inside this rock-cut cave, at sunrise on each day in the months from March to September, the rays of the rising sun penetrate an opening carved into the cupula of the temple and are projected onto one of the walls of the main chamber (see Fig. 11), where they illuminate a cup-mark and pubic-triangle petroglyphs carved in bas relief. This is a unique display of the extraordinary visual language of these cultures, whereby sunlight is projected into and penetrates the opening with its indentations and grooves specifically designed for this purpose, creating a remarkable sequence of images that are projected onto the carvings. In this way, a story that has been told since time immemorial is related using moving visual images with a discourse that speaks of the fertilising role of the Sun on Mother Earth, represented here by the public triangle.

The full astronomical functionality of the monument, which has not yet been fully established and researched, constitutes one of the most exciting archaeoastronomical challenges in island cultures today.

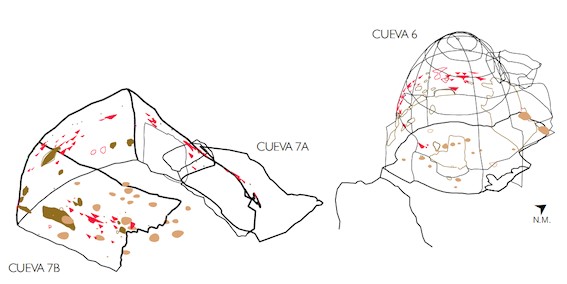

Fig. 12. Map of caves 6 and 7 at Risco Caído. The structural complexity of cave 6, with defined rules of measurement and its parabolic design, bear witness to an incredible knowledge of architecture, astronomy and geology in an isolated culture of this type. Photograph © Carlos Gil Sarmiento, PROPAC

As a work of architecture, the cave-calendar of Risco Caído is the most intricate and perfect structure in this complex. In an isolated culture that did not even use metal, this ingenious accomplishment is a perfect example of an in-depth knowledge of technology, architecture and astronomy (Márquez Zárate, 2013). This area, dug out from the rock with a circular floor, is very unusual in this type of structure on the island. In addition, the parabolic dome, the uniform pattern of measurements and proportions, and the way in which the materials were worked denote a formal originality and extraordinary structural creation in a culture with such limited resources (see Fig. 12). This enclosure is accompanied by another large annexed chamber with a complex system of cup-marks carved into the floor that covers almost its entire surface, which reinforces the ceremonial nature of the site and its possible use in the celebration of rituals.

These sites of clear astronomical and spiritual significance (sanctuaries, astronomical markers and ceremonial enclosures) are elements that form part of a unique cave-dwelling system, with a complex and efficient structure and functionality (dwellings, granaries, burial sites and meeting places). Together they represent an amazing human habitat that merges in perfect harmony with the spectacular geology and natural landscape of the region.

The agricultural activity of the ancestors has also left its mark on this cultural landscape in a colossal display: the “bocao”, a type of crop terrace supported by powerful stone walls. Added to this is the continued existence of paths, trails or evolved expressions of the ancient water culture, such as the water reservoirs in caves.

Fig. 13. Cueva de las estrellas (star cave), Acusa. Photograph © Julio Cuenca

Intangible heritage

The intangible dimension is the astronomical knowledge of the island’s early inhabitants, expressed through their unique calendar and the treatment of concepts as abstract as the equinox (Belmonte, 2008).

At Risco Caído and in the sacred mountain sites of Gran Canaria, we see the language through which the Canarian people provoked intense social emotions: rituals, art, perception effects, and a unique relationship with the cosmos (Tejera Gaspar et al., 2008).

The astronomical sanctuary of Risco Caído bears witness to the existence of an extraordinary knowledge applied in the construction of rock-cut caves, unique in isolated island cultures, and exceptional in terms of their astronomical functionalities.

The structure of the human settlement and the scale of the social and economic organisation are indicative of a culture that was extremely precise and efficient in its use of resources (use of the soil and crops, water management, and use of materials), with an advanced concept of the organisation of territorial and ecological space.

Fragments of this intangible heritage are preserved in certain pre-colonial traditions that, amazingly, still survive. An example is the rural practice of transhumance, common among the shepherds of the various northern regions who move their livestock to the coastal regions and lowlands during the winter and up to the mountain peaks in Tejeda in the summer. Another is the traditional style of pottery-making that uses neither wheel nor kiln; this still persists in the Lugarejos pottery centre on the fringes of the sacred mountain area of Gran Canaria (Cuenca Sanabria, 1987). Added to this is the surprising fact that some of the cave houses at Acusa are still inhabited: this keeps alive the tradition and experience of living in those same caves that were used by the early settlers on the island.

Fig. 14. Cup-marks and pubic carvings paying tribute to fecundity and fertility in the almogarén temple at Risco Caído. Photograph © Cabildo de Gran Canaria

History and development

It is not known exactly when the first settlers of Berber origin colonised the island although 14C dating records human presence as far back as 0 CE. It remains possible that the first settlers arrived before that time. It is certain, however, that for a period of at least 1500 years they developed their own unique culture, in total isolation, untainted by the presence of other peoples—not even from the same region. At the end of the 15th century, this island culture succumbed to the military dominance of the Crown of Castile, which imposed a new economic, social and religious order. In a short period of time this erased all memory of the ancestral culture.

The area of Caldera de Tejeda was one of the native settlers’ last bastions of resistance against the conquest. This area houses the island’s most important sanctuaries (almogaren) and those of the greatest astronomical significance. In the heart of this sacred space a complex and unique culture flourished and grew in a cave-dwelling habitat; it was a culture that merged in perfect harmony with its surrounding environment.

The chronicles of the Conquest indicated that the Canary Islanders used a calendar that they followed strictly in order to organise their agricultural and ritual activities. All of the accounts concur that the worship of celestial bodies was of great importance and that the calendar was based on observing and recording the movements of the sun and the moon throughout the days, months and year (Belmonte & Sanz de Lara Barrios, 2001).

The chronicles that relate the war events describe, with precision, the area of Caldera de Tejeda, particularly Roque Bentayga and its importance as a sacred site.

After the Conquest, the region that formed the very heart of the native culture fell into total disuse. It is only in recent times that it has opened up to the world; this is particularly true since the 1960s when major work was carried out on communication and infrastructure networks to develop tourism on the island. Indeed, it is because it had been forgotten for so long that the cultural and natural heritage of the area has been preserved in such good condition. Furthermore, many of the unique cave settlements have been in continuous use by the local population from the time of the conquest through to the present day (Mesa de Acusa).

In 1996, the almogarén or ceremonial centre of Risco Caído was discovered in the mountains of Gran Canaria. It is an exceptional archaeological complex of religious and astronomical significance that dates back to the time of the early island settlements (Cuenca Sanabria et al., 2008). Its discovery was the high-point of a long process of rediscovery of this area that was of exceptional symbolic and cosmological significance to the native islanders.

Justification for inscription

Comparative analysis

There are more than one hundred thousand small and medium-sized islands in the world, with a huge cultural and natural diversity, as indicated in Chapter 17 of the Río Declaration (1992). Together, they have more than 400 million inhabitants. Yet the World Heritage List, in stark contrast, contains little to represent cultural or mixed sites, including cultural landscapes, on these islands. The List is particularly limited in terms of archaeoastronomical values and expressions.

Risco Caído and the sacred mountains of Gran Canaria bear similarities to some of the few cultural or mixed sites on the List that do relate to ancient island cultures and do include astronomy-related manifestations. Only the following are of particular note:

- Rapa Nui National Park (Easter Island, Chile). The ceremonial platforms (ahus) upon which the so-called moai are erected, may be reinterpreted from an archaeoastronomical viewpoint in the light of new research (Belmonte & Edwards, 2007).

- Heart of Neolithic Orkney (Scotland, UK). Important prehistoric cultural sites and landscapes reflect life in this remote archipelago 5000 years ago. The alignments of these complexes include clear solstice markers.

Only two properties can be cited as expressions of extinct island cultures with stone monuments and cave settlements, and these lack demonstrable astronomical significance: Rock Islands Southern Lagoon (Palau) and Chief Roi Mata’s Domain (Vanuatu). In contrast, this type of site is well represented in non-island areas. Worthy of special mention is the Cliff of Bandiagara (Land of the Dogons) (Mali). The Bandiagara site is an outstanding landscape of cliffs and sandy plateaux with some troglodyte architecture (houses, granaries, altars, sanctuaries and Togu Na, or communal meeting-places). In this relational context, the existence of an astronomical calendar and an unusual cosmology that has survived—albeit with some contamination throughout the centuries—is of particular note (Holbrook et al., 2008).

Some archaeoastronomers have also studied the presence of possible astronomical representations in emblematic Palaeolithic art sites, for example, putative astronomical representations of the constellations in the caves of Lascaux (France) and in Altamira (Spain). However, there are no inscriptions on the World Heritage List for cave settlements or cultural landscapes of this type in island territories, and certainly no mention any containing relics of archaeoastronomical significance.

Other ancient island cultural sites can be found on national Tentative Lists, examples being the Talayotic Culture of Minorca (Spain) and the Ceremonial Centres of the Early Micronesian States: Nan Madol and Lelu, where the archaeoastronomical components (in both sites) are worthy of note but are not determining factors.

In contrast, in the ICOMOS–IAU Thematic Study on the Heritage Sites of Astronomy and Archaeoastronomy (Ruggles & Cotte, 2010), there are cases of islands that can be deemed similar in that they contain sites of archaeoastronomical interest. The Thematic Study has identified some sites that relate to primitive island cultures such as the navigation temple at Holo Moana in Hawai‘i, or the Caroline Islands, that are considered manifestations of the astronomical knowledge of the native island inhabitants of the Pacific and their unique calendars. It is also important to highlight the ceremonial site of Caguana in Puerto Rico, which is considered the most important archaeological site in the West Indies, and Atituiti Ruga in French Polynesia, both of with had the possible function of observing and predicting astronomical events.

In its role as navel of the world, and of the cosmos, for this ancient Canarian culture, the sacred mountains of Gran Canaria are also related to other key sites in the Canary Islands that have played an important role in the cosmology of its primitive peoples. Those worthy of special mention include El Teide, a natural site included in the World Heritage List, and Tindaya Mountain in Fuerteventura, whose sculpted “footprints” of the ancient “majos” at its summit constitute another example of island archaeoastronomy.

Gran Canaria is clearly exceptional in this context, in that it incorporates manifestations of an ancient island culture, now extinct, that created a complex troglodyte habitat and a unique cultural landscape in which astronomical sanctuaries played a key role.

Integrity and/or authenticity

Integrity

All the structures that form part of the complex of sanctuaries (almogarenes) with astronomical and ritual functionality that have been referenced in the sacred sites of this part of the island have been kept unaltered. This includes the recent discovery at Risco Caído which was not mentioned in the chronicles and other available sources.

The fact that the cave habitat and aforementioned sanctuaries together with the basic elements of the area and landscape in which the early inhabitants lived have been preserved intact provides all the requisite elements upon which their outstanding universal value might be established.

The size of the conservation area containing all of the listed archaeological zones (see Fig. 3) is adequate, as is the set of events required to understand the characteristics of this ancient culture and its worldview.

The loss of a substantial part of the chattels (utensils, personal belongings, grave goods etc.), does not affect the basic elements that inform us about and help us to interpret the astronomical, economic and social pillars of this ancient culture.

Fig. 15. Roque de Cuevas del Rey (King’s Cave rock), which houses numerous artificial caves that form a huge collective granary. Photograph © PROPAC

Authenticity

Fortunately, and in contrast to other prehistoric cultures, written accounts of the native islanders can be found in the chronicles, which, although rare and dispersed, constitute a key legacy when it comes to understanding the key factors of the social organisation, rituals and astronomical knowledge of the people who inhabited these lands.

From the 14th century onwards, Portuguese and Majorcan voyagers started to make direct reference to the inhabitants of the islands. But most of the information available today was collected in the 16th century by those known as the “chroniclers”, when the archipelago was first conquered by the Crown of Castile. Their chronicles also bear witness to how the European conquistadores were impressed by this culture: they contain detailed descriptions of some of its structures, beliefs and social organisation (Arias Marín de Cubas, 1986 [1694]).

The chronicles from the conquest give accounts of how the native inhabitants used a calendar that they followed strictly in order to organise their agricultural and ritual activities. All the accounts speak of the great significance of worshiping celestial bodies and that this calendar was based on the observation and recording of movements of the sun and the moon throughout the days, months, and year. “Their year, which was called Acano, was based on lunar months with 29 suns from the date of the new moon; it started in summer as the sun started to enter Cancer on 21 June at the first conjunction and for nine continuous days they held great dances and banquets and marriages, having sold their crops, they carved Tara and Tarja symbols into boards, walls or stones to commemorate same” (Arias Marín de Cubas,1986: 254 [1694: 74]).

The accounts of acts of war also described, with some precision, the area around Caldera de Tejeda and particularly Bentayga rock, which was one of the last bastions of resistance of the native islanders against the conquest. A more recent complementary description was given by travellers, scientists and naturalists in the 19th century and the early 20th century.

However, detailed research, categorisation and identification of this exceptional heritage has only been carried out in the last two decades and more particularly since the discovery of the almogarén at Risco Caído.

During this time, identifying the artefacts and establishing the authenticity of their attributes has been the object of many studies and much research work involving many disciplines and institutions. Studies have been carried out, firstly, by the Historical Heritage Department of the local government of Gran Canaria and its experts and researchers, this being the entity most directly involved in the preservation of this heritage. Important archaeologists and anthropologists such as Julio Cuenca Sanabria (discoverer of Risco Caído) have also based their research work in this area in recent decades. Also worthy of special note are the archaeological studies carried out in the Bentayga area by the Archaeology Service of El Museo Canario (SAMC).

The astronomical significance of these monuments has been the subject of study for some time by well-known researchers in the area of cultural astronomy (Aveni & Cuenca Sanabria, 1994; Belmonte, 2000). Numerous academic studies have been carried out on the calendar of the early inhabitants of the island (Barrios García, 1997).

Fig. 16. Ground-penetrating radar survey of cave 6 at Risco Caído. Photograph © Julio Cuenca

Fig. 17. Results of the ground-penetrating radar survey of the cave-sanctuary at the troglodyte settlement at Risco Caído. Photograph © Cabildo de Gran Canaria

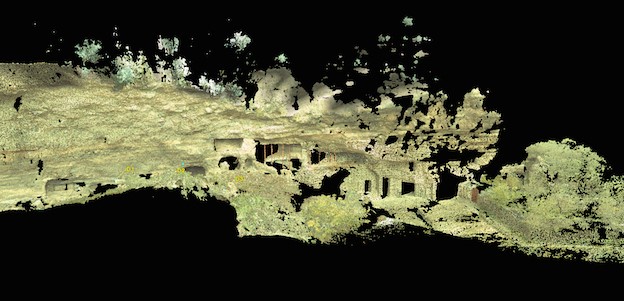

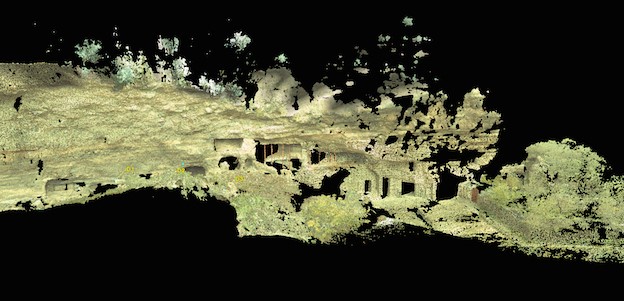

A comprehensive ongoing project at Risco Caído, led by the archaeologists Julio Cuenca and José de León, has the support of an interdisciplinary team of professionals from different areas of expertise that are involved not only in archaeological and archaeoastronomical research work but also in a geological, geomorphological and petrological analysis of the entire area. Likewise, the latest technologies available are being used to study the archaeological complex in order to support research, conservation, protection and analysis of the authenticity of the artefacts in question. Surveys have thus been carried out using laser scanning to capture point clouds, and advanced photogrammetric methods are being used to study the rock art found inside the artificial chambers or caves; probing by ground-penetrating radar is being carried out to determine the existence of any possible internal defects in the caves.

The year 2013 saw the launch of a series of International Workshops about Risco Caído and the Sacred Mountain sites, promoted by the Historical and Cultural Heritage Department of the local government. The aim of these was to investigate the attributes, authenticity and uniqueness of the properties in question and of the landscapes (natural and cultural) associated with the area. The conclusions of this are currently in the process of being published. In this context, relevant seminars and working visits such as those of Clive Ruggles in 2013, from the University of Leicester, who is IAU co-ordinator of UNESCO’s Astronomy and World Heritage Initiative, and Juan Antonio Belmonte from the Astrophysics Institute of the Canary Islands (IAC) and president of the European Society for Astronomy in Culture (SEAC). Further events were held in 2014, which were attended by experts and scientists from many disciplines including Michel Cotte, spokesman for ICOMOS at the World Heritage Committee, Josep María Mallarach from the IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas, Manuel Martín-Loeches from the UCM-ISCIII Centre, Cipriano Marín, coordinator of the Starlight initiative, and Leonardo García Sanjuán from the University of Seville.

The unique features of these monuments, and particularly those at Risco Caído, have been analysed from an architectural point of view in various studies as well as in research projects that demonstrate their unique structural design (see Fig. 12). Such work has also revealed, for example, the important fact that these structures were built following precise rules of measurement (Márquez Zárate, 2013).

In terms of geo-diversity, biodiversity and landscape, this area constitutes one of the most studied areas in Europe. An in-depth summary of the attributes can be found in key documents such as the Biosphere Reserve Declaration report and the Natural Resources Ordinance Plan.

Criteria under which inscription might be proposed

-

Criterion (i): The astronomical design and the construction techniques used at Risco Caído, which embody exceptional and unique geological, geotechnical, geometric, astronomical or luminotechnical knowledge, represent a masterpiece of human genius and creativity in a situation of absolute isolation. Its architectural design which encompasses both religious and astronomical functionalities, constitutes an exceptional accomplishment within the realm of ancient rock art manifestations on islands.

-

Criterion (iii): This complex of archaeological sites is an exceptional and unique testimony to an ancient island culture, since disappeared, that had a highly developed knowledge of astronomy, and which evolved in isolation over a period of more than 1500 years. This heritage is illustrative of the odyssey of the many cultures that have settled on the islands of this planet and that have evolved over long periods of time without external influences, thus creating their own cosmology and a wealth of knowledge and beliefs that are extraordinarily unique.

-

Criterion (v): The cave settlements at Caldera de Tejeda and the surrounding area are an exceptional example of this type of human habitat in ancient island cultures, illustrating a level of organisation of space and use of natural resources that is both highly efficient and complex. The colossal geological backdrop and the natural landscape fuse with the rock art cave dwellings, structures and terraces, creating an authentic “cultural landscape” that still retains its symbolic and cosmological connotations.

Suggested statement of OUV

Risco Caído and the sacred mountains of Gran Canaria host a complex of well-preserved archaeological sites and cultural landscapes belonging to an insular culture, now extinct, that evolved in isolation after the arrival of the first Berbers or amazighs from North Africa around the beginning of the first century AD until the time, around the late 13th and early 14th centuries, when seafarers from southern Europe came to the islands in search of new spice routes and slaves for the slave trade. This is, therefore, an exceptional heritage that expresses a unique and unrepeatable cultural process that we are only now beginning to understand.

The site is organised and can be understood in terms of its cosmological vision. This is what determines the configuration of this unique troglodyte habitat that is presided over by unique geological events and the existence of natural and cultural landscapes, the most basic elements of which have been preserved intact to this day.

The highly sophisticated nature of the astronomical markers, particularly Risco Caído and Roque Bentayga, constitute a landmark without precedent in ancient island cultures, even when compared with megalithic sites of renown throughout the continent. Their unique value lies in how a proto-state society, isolated, and with very limited technology, could attain such a sophisticated knowledge of astronomy as that expressed in its calendar and in how it dealt with astronomical concepts as abstract as the equinoxes.

The sanctuary and astronomical marker at Risco Caído represents a unique architectural masterpiece, both in terms of its conception and its functionality, its design and the structural and symbolic elements contained therein. This site can and should be seen as a unique and extraordinary phenomenon in the evolution of the rock-cut architecture of the early inhabitants of the island and as an ingenious marker that embodies ancient cosmology and sacred symbolism in the context of the ancient island cultures of our planet.

State of conservation and factors affecting the property

Present state of conservation

The archaeological sites are well preserved but are under threat from humans in terms of the level of protection and surveillance afforded to them. The sites have adequate perimeter protection. Since 2002, the local government, Cabildo de Gran Canaria, has been responsible for protecting the historical heritage of the island and, as such, it has been making great strides in safeguarding the conservation and maintenance of the complex, which has included the purchase of the main landmarks such as Risco Caído and other lands of interest.

The sites, and the caves in particular, are not currently occupied, other than for scientific, cultural and educational use. An exception is the cave houses at Acusa, which are inhabited: this has played an important role in their being so well preserved. Looting, which had a huge impact on the archaeological resources of the Canary Islands in the 19th century and the early 20th century, is no longer an issue.

The current risks are environmental in nature. These include erosion and certain defects in the cave structures. In some cases, like at Risco Caído, careful studies are being carried out on the condition of the caves and their degree of fragility. These include studies being carried out by geologists such as Ismael Solá and the Eduardo Torroja Institute of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC).

In terms of landscape biodiversity, the fact that the area has been declared a protected area guarantees the active and total conservation of its resources. The degradation processes of the past have given way to a new culture aimed at restoring habitats and landscapes.

Fig. 18. View of Bentayga rock, the ceremonial and cosmological epicentre of the Caldera de Tejeda, at the base of Roque Nublo. Photograph © Cabildo de Gran Canaria

Factors affecting the property

Developmental pressures

The growth of infrastructure (roads, bridges, etc.) poses the main threat to the integrity of the sites, which could also be vulnerable to changes in land use and urban occupation phenomena. In relation to this, the Historical Heritage Service of the local government has drawn up a “Charter of Risks” to assist in the implementation of the necessary preventive measures. In any case, urban development is not a risk factor given that, under current legislation, the land in the area is not deemed suitable for development (GESPLAN, 2010).

Environmental pressures

There are no significant environmental pressures. Nevertheless, it is important to highlight certain aspects that affect the integrity of the landscape in which the sites are located, such as invasive species or the maintenance of walls and terraces affected by the passage of time. Another threat to the scenic integrity of the areas is the relative growth in light pollution, which needs to be controlled so as to maintain the quality of the night sky as an important environmental resource associated with the proposed sites.

Fig. 19. Partial view of the cave houses at the troglodyte settlement at Acusa, a popular spot for locals and tourists alike. Photograph © Cabildo de Gran Canaria

Visitor/tourism pressures

Visitor numbers are quite manageable at present and are within an acceptable range. However zoning should be carried out in the future, based on the admissible load capacity of each site.

No. of inhabitants

There is no discernible population pressure in the area. Indeed, the municipalities of Artenara and Tejeda have the lowest population density on the island (2), in contrast to the island average of 546 inhabitants/km2 (ISTAC, 2012).

Protection and management

Ownership

The Cabildo de Gran Canaria (the local government of the island) owns the main archaeological sites and the surrounding areas, including Risco Caído, with the exception of some of the caves at Acusa, which belong in many cases to the owner occupiers. The Cabildo also owns the land at Guayedra. As regards use of resources it should also be pointed out that Tamadaba is listed as a mountain of public interest.

Protective designation

All of the archaeological sites mentioned are included on the archaeological charter and, as they include cave art, they are also listed in their own right as Sites of Cultural Interest in Spain in accordance with article 62 of Law 4/99, on the Historical Heritage of the Canary Islands. In all cases, proceedings have been or are being initiated to designate boundaries around the archaeological areas. At Risco Caído, in particular, proceedings are currently being processed. Alongside the sites already mentioned is the troglodyte settlement at Barranco Hondo near to Risco Caído. An ethnographic map of Gran Canaria that identifies and defines all the sites of ethnographic interest directly or indirectly related to this submission is also available.

The environmental and landscape integrity of the area under consideration is likewise safeguarded thanks to its inclusion as a protected area in the Canary Island Network of Natural Protected Areas, which safeguards the area against the intense development and transformation being experienced in the island. The area under consideration is subject to three types of protection: Nublo nature reserve, Roque Nublo Natural Monument and the Tamadaba nature reserve. Use of these areas is regulated by the respective Use and Management Steering Plan and Conservation Rules applicable in each case, which deal with the preservation of the sites in question and the surrounding landscape. In addition, the entire sacred site is included in the Special Area of Conservation (SAC) forming part of the European Natura 2000 network.

This sacred site of the early settlers on the island is nestled in the northern part of the Gran Canaria Biosphere Reserve (see Fig. 4). UNESCO’s 26th International Co-ordinating Council of the Man and the Biosphere Programme held in June 2014 proposes the possibility of a common strategy to unify those sites declared biosphere reserves that are either fully or partially registered on the World Heritage List, highlighting the confluence of natural and cultural values. This case could be one of the first models to adopt such a holistic approach that considers heritage as a whole including its natural, cultural and spiritual aspects.

Visitor facilities and infrastructure

The Bentayga Interpretive Centre was officially opened in 2013. It is located in the heart of the sacred site, in Roque Bentayga Archaeological Park (see Fig. 20). The centre opens a door to the sacred site and to knowledge of the culture of the early settlers on the island and the natural values of the area. The rituals and astronomical knowledge dimension is a significant part of the museum and interpretive centre resources. The centre provides a platform for guided visits around the area using the island’s network of walking routes, and includes visits to the almogarén at Bentayga. The activities at the centre are developed in collaboration with the local people and the main players in the tourist and economic sectors in the area. It is managed by a cooperative.

The Casas Cuevas Museum at Artenara is another centre that can be considered a worthy prelude to a visit to the troglodyte settlements of the area, such as, for example, Acusa Seca and the cave house neighbourhood of Barranco Hondo. This ethnographic dimension is complemented with other offerings such as the pottery centre, Centro Locero de Lugarejos, which focuses on traditional earthenware as was used by the early settlers on the island.

However, it is important to bear in mind that certain structures and sites are very fragile and have a limited load capacity. This is the case at the Risco Chapín caves and at the almogarén itself at Risco Caído. For this reason, Gran Canaria’s local government has set the wheels in motion for a new interpretive centre to be built at Artenara, which will focus more on the cosmological vision and the archaeoastronomical values of the area. Using the laser-scanning surveys carried out at Risco Caído, reproductions of these spaces will be made to scale using advanced virtual resources in order to give better insights into the development which, it is hoped, will lower the footfall of visitors to the more sensitive areas.

Fig. 20. The interpretive centre at Roque Bentayga, an example of the ongoing efforts made to raise awareness in general and amongst visitors of this exceptional heritage and the need to protect it. Photograph © Gaia Consultores

Documentation

Photos and other AV materials

- Virtual recreation of caves no. 6 and no. 7 at the astronomical sanctuary at Risco Caído, Artenara, Gran Canaria

- Video about Risco Caído

- “Es Todo Tuyo”—the information portal on the archaeological, ethnographic and architectural heritage of Gran Canaria by the Cabildo de Gran Canaria

- Biosphere Reserve Page

Texts relating to protective designation

- Law 4/1999 on the Historical Heritage of the Canary Islands

- Law 12/1994 on Protected Natural Areas of the Canary Islands

- Gran Canaria Biosphere Reserve

Bibliography

Arias Marín de Cubas, T. (1986 [1694]). Historia de las Siete Yslas de Canaria. Edited by áüngel de Juan Casaras & María Regul Rodríguez, with archeological notes by Julio Cuenca Sanabria. Real Sociedad Económica de Amigos del País, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

Aveni, A.F., Cuenca Sanabria, J. (1994). Archaeoastronomical fieldwork in the Canary Islands. El Museo Canario, 49, 29–51.

Barrios García, J. (1997). Sistemas de numeración y calendarios de las poblaciones bereberes de Gran Canaria y Tenerife en los siglos XIV-XV. Universidad de La Laguna.

Belmonte, J.A. (ed.) (2000). Arqueoastronomía Hispánica. Prácticas astronómicas en la Prehistoria de la Península Ibérica y los archipiélagos balear y canario, 2nd edn. Equipo Sirius, Madrid.

Belmonte J.A. (2008). Tiempo y Religión: una historia sagrada del calendario. Ediciones Clásicas-Ediciones del Orto, Madrid.

Belmonte, J.A., Edwards, E, (2007). Astronomy and landscape in Easter Island: New hints at the light of the ethnographical sources. In: Emília Pásztor (ed.), Papers for the annual meeting of SEAC (European Society for Astronomy in Culture) held in Kecskemét, Hungary in 2004, BAR International Series 1647, Archaeopress, Oxford, pp. 79–85.

Belmonte, J.A., Esteban, C., Schlueter, R., Perera, M.A., González, O. (1995). Marcadores equinocciales en la Prehistoria de Canarias. Noticias del I.A.C, 4, 8–12.

Belmonte J.A., Hoskin M. (2002). Reflejo del Cosmos. Equipo Sirius, Madrid.

Belmonte, J.A., Sanz de Lara Barrios, M. (2001). El Cielos de loas Magos: tiempo astronómico y meterológico en la cultura tradicional del campesinado canario. Ediciones La Marea, Santa Cruz de Tenerife.

Carcavilla Urquí, L., Palacio Suárez-Valgrande, J. (2011). Geosites: aportación Española al patrimonio geológico mundial. IGME [Instituto Geológico y Minero de España], Madrid.

Cuenca Sanabria, J. (1987). La alfarería tradicional de Gran Canaria y sus relaciones con el mundo bereber. In: Manuel Olmedo Jiménez (ed.), España y el Norte de Africa: bases históricas de una relación fundamental : aportaciones sobre Melilla, Vol. 1, Universidad de Granada, Granada, pp. 99–112.

Cuenca Sanabria, J. (1994). Nueva estación de grabados alfabetiformes en el Roque de Bentayga. El museo canario, 49, 101–105.

Cuenca Sanabria, J. (1995). Nueva estación de grabados alfabetiformes del tipo líbico-beréber en el Roque Bentaiga, Gran Canaria. El museo canario, 50, 79–94.

Cuenca Sanabria, J., (1996). Las manifestaciones rupestres de Gran Canaria. In: J. Cuenca Sanabria & A. Tejera Gaspar (eds), Manifestaciones Rupestres de las Islas Canarias, Dirección General de Patrimonio Histórico, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, pp. 133–222.

Cuenca Sanabria, J., García Navarro, M., González Arratia, L., Montelongo, J. (2008). El culto a las cuevas entre los aborígenes canarios: el almogaren de Risco Caído (Gran Canaria). Almogaren, 39, 153–190.

Cuenca Sanabria, J. Rivero López, G., (1994). La Cueva de los Candiles y el Santuario del Risco Chapín. El museo canario, 49, 59–99.

GESPLAN (2010). Plan de Zona Rural de la Isla de Gran Canaria. Gobierno de Canarias, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

Holbrook, J. C., Urama, J. O., Medupe, R. T. (eds) (2008). African Cultural Astronomy Current Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy research in Africa. Springer, New York.

ISTAC (2012). Estadística del Padrón Municipal: Población, variaciones y densidades por islas. Instituto Canario de Estadística. Gobierno de Canarias. http://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/istac/

López Peña, F., Cuenca Sanabria, J., Guillén Medina, J. J. (2004). El triángulo público en la prehistoria de Gran Canaria: nuevos hallazgos arqueológicos In: Francisco Morales Padrón (ed.), XV Coloquio de historia canario-americana, Cabildo Insular de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, pp. 2243–2264.

Martín, J.L. (2010). Atlas de biodiversidad de Canarias. Gobierno de Canarias, Santa Cruz de Tenerife.

Márquez Zárate, J.M. (2013). Research results presented at the 2nd International Workshop on Risco Caído and the Sacred Mountains of Gran Canaria. Unpublished.

Ruggles, C. & Cotte, M. (2010). Heritage Sites of Astronomy and Archaeoastronomy in the context of the UNESCO World Heritage Convention: a Thematic Study. ICOMOS–IAU, Paris.

Tejera Gaspar, A. , Jiménez González, J. J., Allen, J. (2008). Las manifestaciones artísticas prehispánicas y su huella. Gobierno de Canarias/Canarias Cultura en Red, Santa Cruz de Tenerife.

No multimedia content published

Currently there is no multimedia content published for this case study