Category of Astronomical Heritage: tangible immovable

The Jantar Mantar at Jaipur, India

Presentation

Geographical position

City of Jaipur, State of Rajasthan, India.

Location

Latitude 26° 55′ 29″ N, longitude 75° 49′ 28″ E. Elevation 440m above mean sea level.

General description

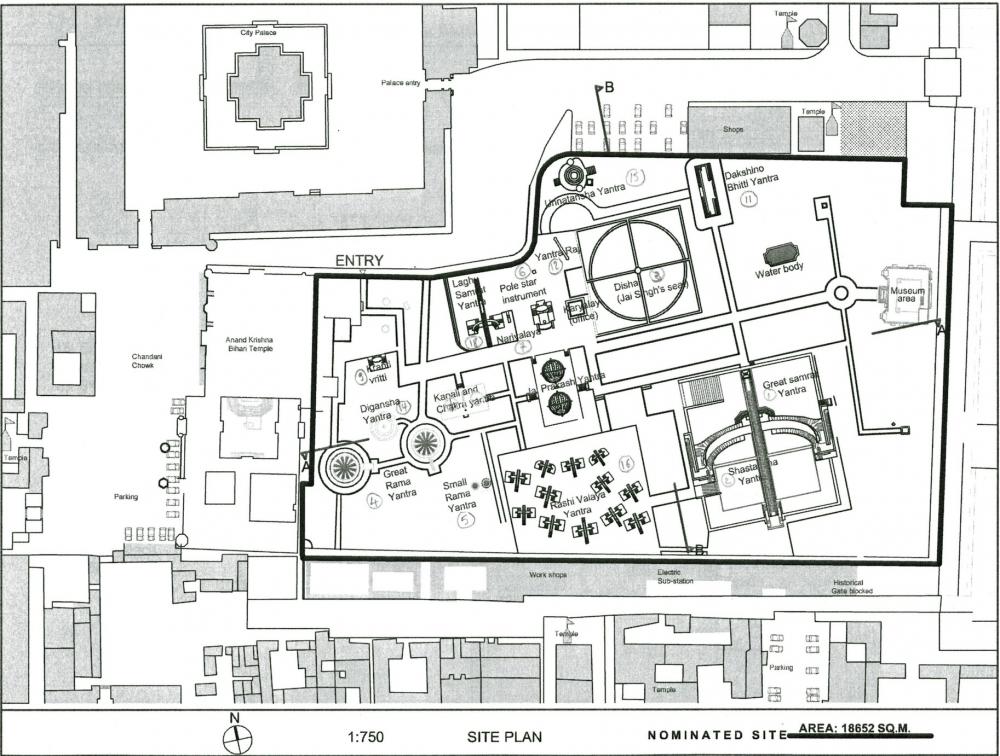

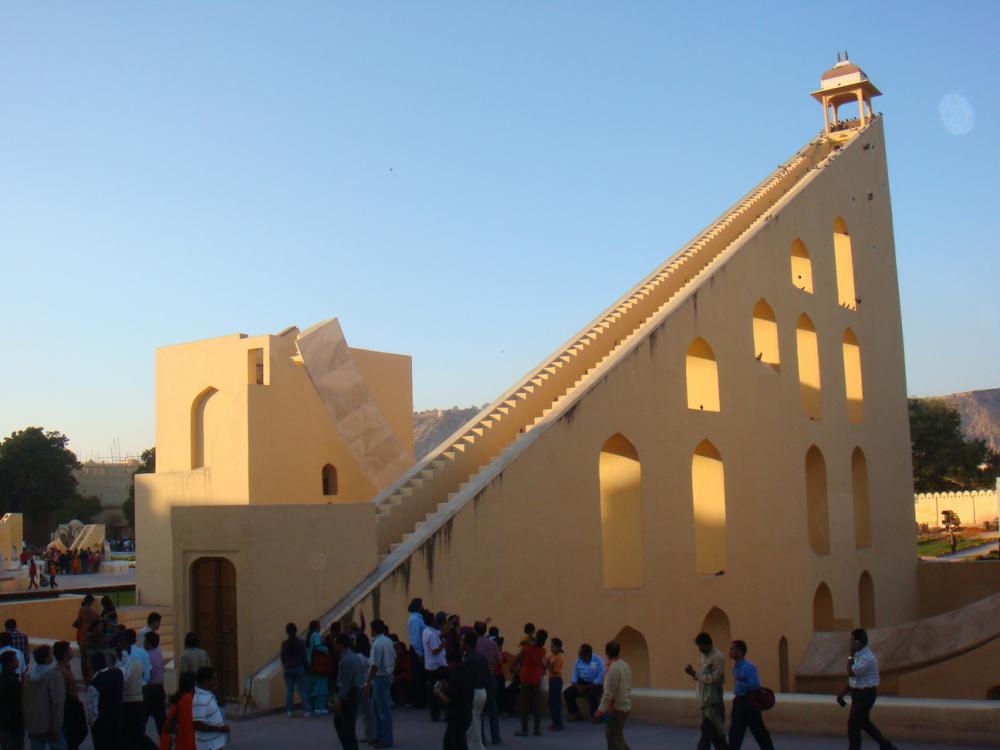

The Jantar Mantar of Jaipur is an observatory built in the first half of the 18th century. Today it has 19 main astronomical instruments or groups of instruments. They were generally constructed of brick rubble and plaster, but a few were made of bronze. They were built for naked-eye observations of the celestial bodies and precision was achieved through their monumental dimensions. Generally speaking, they replicated the design of earlier instruments, but the site shows important architectural and instrumental innovations and the size of some of the instruments is among the largest in the world. There are instruments working in each of the three main classical coordinate systems: the horizon-zenith local system, the equatorial system and the ecliptic system. One instrument (Kapala Yantra) is able to work in two systems and to transform coordinates directly from one system to the other. This is one of the most complete and impressive collections in the world of pre-telescopic masonry instruments in functioning condition.

Brief inventory

The most significant instruments (yantras) among the collection are:

- Brihat Samrat, probably the largest gnomon-sundial ever built. With a gnomon arm 22.6m high and two lateral quadrants of radius 15.15m, it measures local time to an accuracy of 2 seconds.

- Sasthamsa, which has four large meridian dials inside two high black chambers.

- Jai Prakash, a highly innovative sundial made of two hemispherical bowls that produce an inverse image of the sky and allow the observer to move freely around inside to take readings.

- Great Ram is a rare, and perhaps unique, double-cylinder instrument to record the azimuth of celestial bodies;

- Raj comprises a bronze astrolabe 2.43m in diameter, probably the largest in the world.

- Kapala is able to record the co-ordinates of celestial bodies in both the azimuth-altitude and equatorial systems, and permits a direct visual transformation of the co-ordinates of any point in the sky between the two systems;

- Rasivalaya is a unique group of 12 gnomon-dials to measure the ecliptic co-ordinates of celestial objects, each becoming operative when a different one of the 12 zodiacal constellations straddles the meridian.

History

The Jantar Mantar Observatory was built by Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II, as a focal point of his new capital, Jaipur, the first and earliest geometrically planned city in India. Jai Singh II was one of several powerful princes rising to power as the influence of the Mughal Empire decreased. In his attempt to become an almost independent ruler of Rajasthan, he started to build a new capital underlining the link between scientific capacities, urban planning and social control. The construction of the observatory site started in the 1720s and was completed in 1738.

Jantar Mantar is the most complete and best-preserved great observatory site built in the Ptolemaic tradition. This tradition developed from Classical Antiquity through to Medieval times, and from the Islamic period through to Persia and China. Jantar Mantar was greatly influenced by earlier great observatories inside central Asia, Persia and China.

The observatory was very active during the life of Jai Singh II, with around 20 permanent astronomers. After his death in 1743, this key landmark in the centre of the capital city of Rajasthan remained in use almost continuously until around 1800. This is evident from the fact that repairs were carried out at least twice during this period. Nevertheless, during the 19th century the site ceased to function permanently as an observatory, being re-opened from time to time between periods of low activity or complete abandonment. Some important restorations occurred at the end of the 19th century, and mainly in 1902, under British rule. This started a new life for the observatory as a monument of Rajasthan. Other campaigns of restoration occurred during the 20th century and the most recent took place in 2006-07.

Cultural and symbolic dimension

The main aims of Jai Singh II’s scientific programme were to refine the ancient Islamic zīj tables, to measure the exact hour at Jaipur continuously and to define the calendar precisely. Another aim was to apply the cosmological vision deriving from the Ptolemaic one, based upon astronomical facts, to astrological prediction—both social (e.g. predicting monsoon and crops) and individual (e.g. printing almanacs). This was an important period for the popular adoption into the ancient Hindu tradition of astronomical data coming from Islamic and Persian civilization. The interweaving of science, cosmology-religion and social control has had a great importance in Rajasthan culture since the 18th century, and continues into current times.

Authenticity and integrity

The main issue here is the number of repairs and sometimes almost complete restorations through the centuries.

In relation to scientific issues and symbolic significance, the integrity of the current property is no less satisfying than that of the original one. Wherever destruction has taken place in order to facilitate restoration, the functional capabilities of the instruments have been safeguarded.

The authenticity of the different instruments is a more complex issue. Most of the scale graduations were originally made of grooves cut in hydraulic lime plaster surfaces, either left open or filled with lead. Just few were made of engraved marble. However, the twentieth-century restorations tended to change this proportion, replacing plaster by marble. During restorations, some staircases were added or modified, new materials were used in rebuilding, and the coating of walls was completely renewed. In some cases it is difficult to know the exact appearance and the detailed structure of the original instrument. It also seems that some Western re-interpretations of the graduated scales took place during the early 20th century.

Documentation and archives

The public offices of the Government of Rajasthan and the Jaipur Library hold important collections of archives and documents. The Department of Archeology and Museum of Rajasthan keep all the works records since 1968.

Management and use

Present use

The site is used for tourism, with more than 700,000 annual visitors in 2006–08. Furthermore, the instruments are in a usable state, and staff or authorized persons are able to perform astronomical observations.

The site is managed by the Department of Archeology and Museum of Rajasthan. The official local staff has around 12 members. Maintenance and survey tasks are subcontracted to private companies, involving around 30 permanent workers on site.

State of conservation

Following a significant programme of architectural maintenance and restoration that took place in 2006–07, the general state of conservation of the Jantar Mantar seems good. Nevertheless, the metal instruments need some renovation and perhaps some restoration.

Main threats or potential threats

The main threats to the site appear to come from:

- the intense and increasing tourist use of the site;

- some water penetration inside the foundations due to rains and to watering during dry seasons; and

- urban pollution.

Protection

Jantar Mantar is a public property and is governed by the Archeological Sites and Monuments Act of Rajasthan (1961). It is also protected as a National Monument of Rajasthan (1968).

Context and environment

The property is set within the historical city of Jaipur, close to the former Royal Palace. It remains close today to the Hawa Mahal Palace and to the City Palace. This buffer zone is both a dense urban landscape and a historical environment of huge importance.

The authorities intend to reshape the landscape around the site for better use in harmony with urban constraints and development: road traffic, car parks, pedestrian access for tourists, etc.

Archaeological / historical / heritage research

For the protection and assessment of the site, the staff produce regular photographic documentation in similar viewing conditions. For science, the main goal is to maintain the instruments through use, by increasing their capacities for current users. For improving the global authenticity-integrity of the site, there is a programme of research and restoration devoted to the historical landscape and natural environment of the monuments.

Management, interpretation and outreach

The Jantar Mantar of Jaipur was inscribed on the World Heritage List in July 2010 under criteria (iii) and (iv).

No multimedia content published

Currently there is no multimedia content published for this case study