Category of Astronomical Heritage: tangible immovable

King's Observatory, Kew, Richmond, UK

Description

Geographical position

King’s Observatory/Kew Observatory, Old Deer Park, Kew in London Borough of Richmond upon Thames Richmond, TW9 2SB, UK

Location

Latitude 51°28’08’’ N, Longitude 0°18’53’’ W, Elevation ...m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code

-

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage

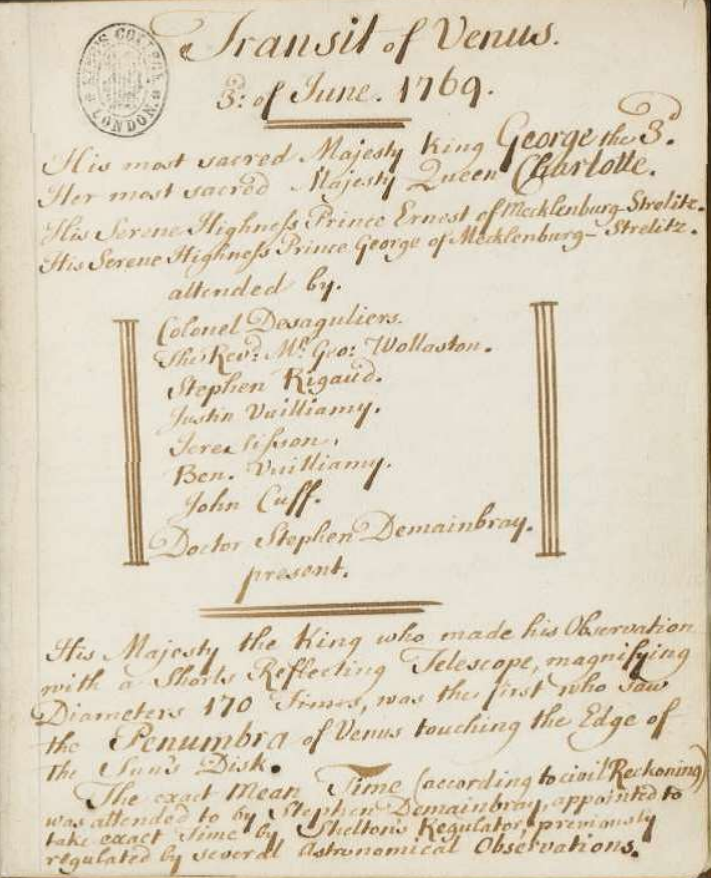

Fig. 1a. King’s Observatory, founded by King George III in order to observe the Transit of Venus (1769) (courtesy of The King’s Observatory)

King’s Observatory -- since 1871 Kew Observatory -- in Richmond, London, was founded by King George III (1738--1820), King of Great Britain and Ireland since 1760, King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until 1820, who had a passion for science (mechanics, optics, electrostatics, alchemy/chemistry), especially astronomy, and scientific instruments, also for the instruction of the princes.

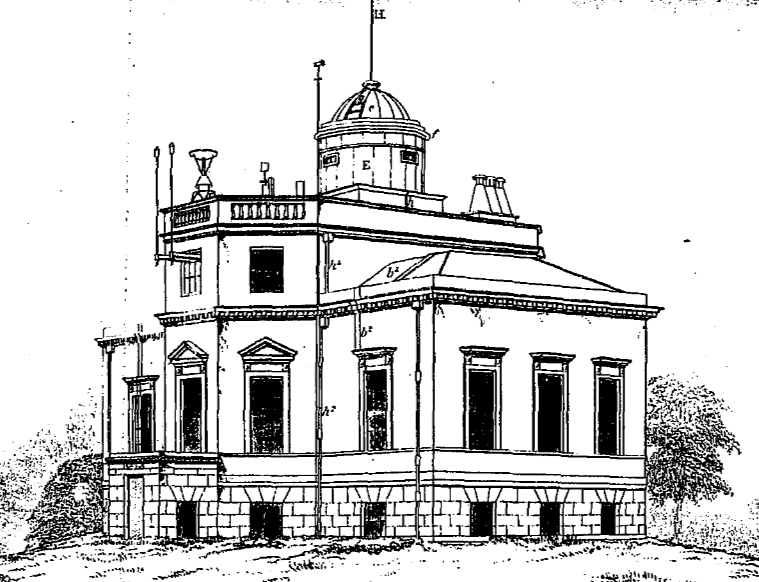

Fig. 1b. King’s Observatory, designed by William Chambers (1769) (historical sketch)

The Swedish-Scottish architect Sir William Chambers (1723--1796) designed King’s Observatory. The foundation of the observatory was inspired by the Transit of Venus event (June 3rd 1769), which the King George III wanted to observe. The Kew Observatory is enclosed by the wonderful Old Deer Park of 2.8 ha.

Chambers, born in Gothenburg, travelled to China as employee of the Swedish East India Company (1740--1749) and was impressed by the Chinese architecture (Dissertation on Oriental Gardening, 1772); one of his master works is the Chinese Pagoda (1761) in the Kew Royal Botanic Gardens. After having studied architecture in Paris and the classical orders, he started his career in London, where he became Architect to the King ( Somerset House in London, 1776--1796) -- besides Robert Adam (1728--1792). Chambers, Knight of the Polar Star, built Kew Observatory of Portland stone in the Early Classical Revival style with elements of the architecture of Andrea Palladio (1508--1580), whom he admired. Palladio’s Renaissance architecture is characterized by aesthetic principles of proportion, harmony and balance -- taking into account the requirements of the building function. Palladianism greatly influenced the architecture committed to classicism. The observatory has a rusticated ground floor, five window axes, three floors, in the center an octagonal room, and on the roof platform -- very remarkable -- the fully revolving dome, the oldest of its type in the world, and still fully functional.

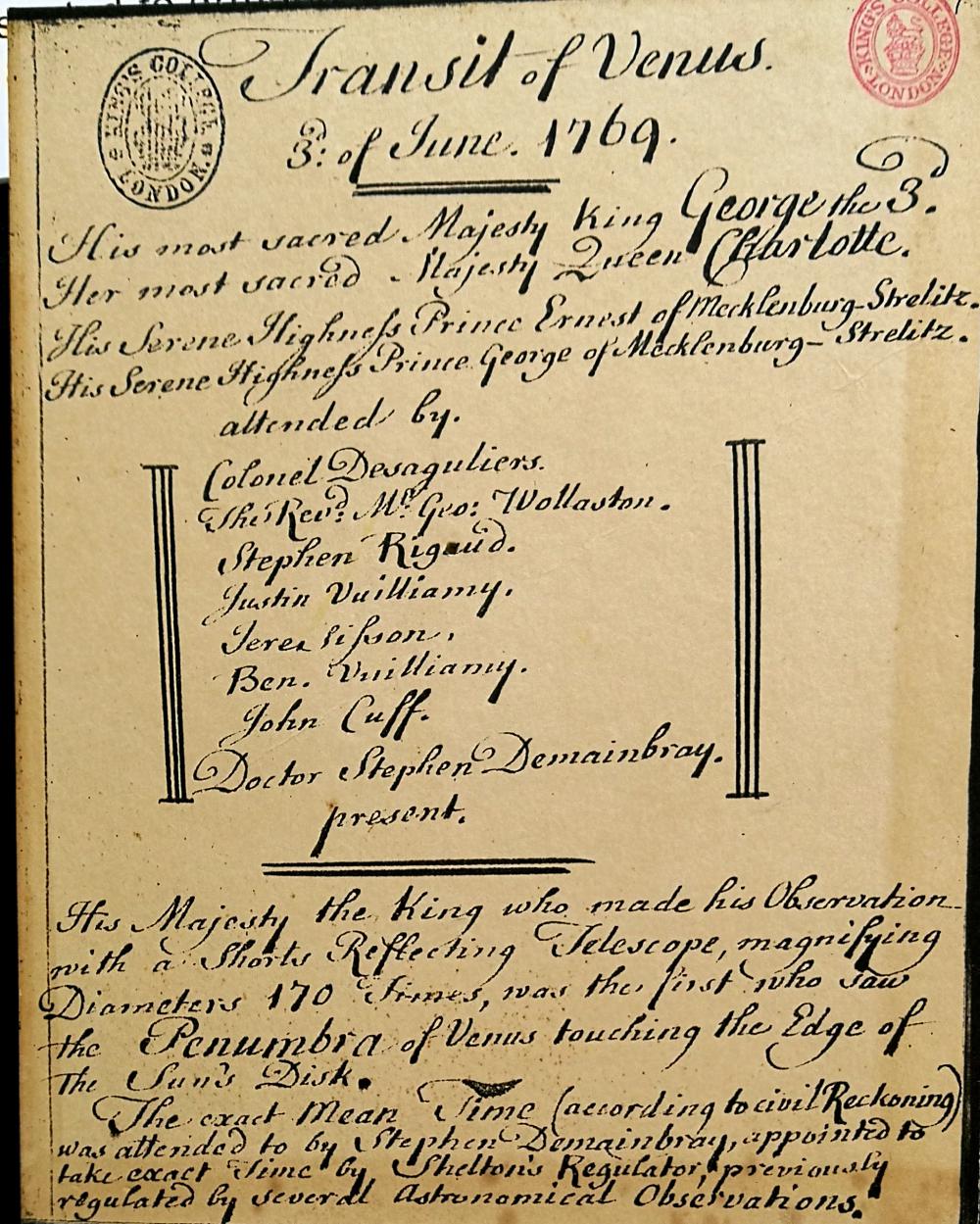

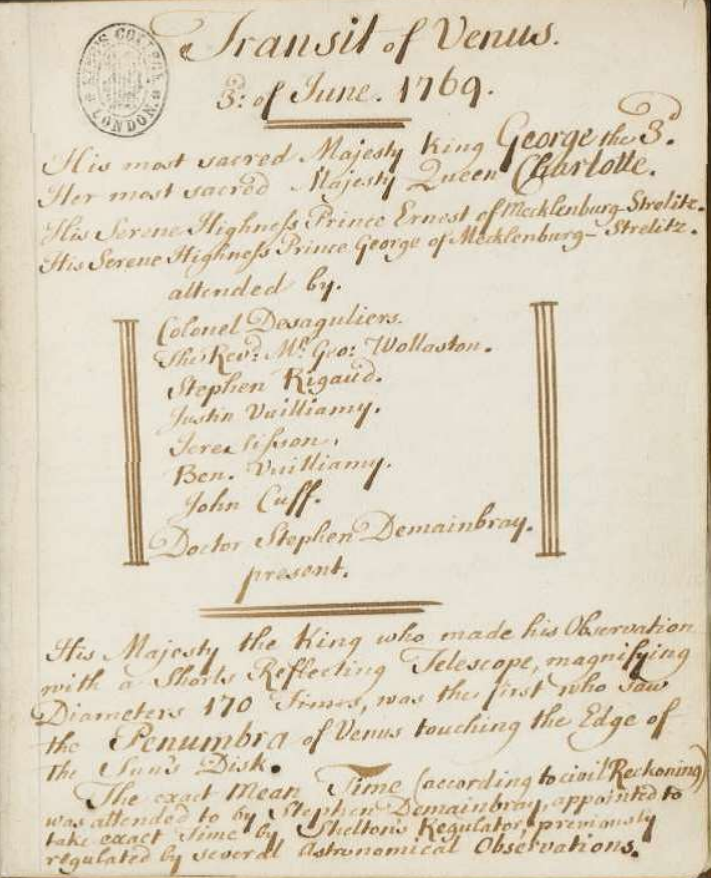

Fig. 2. Extract from Observations on the Transit of Venus (1769), a manuscript notebook from the collections of George III, showing George, Charlotte and those attending them (Wikipedia)

Kew Observatory influenced the architecture of two Irish observatories: Armagh Observatory (1790) and Dunsink Observatory Dublin (1785).

Three obelisks in the Old Deer Park are meridian marks were used for adjusting the transit instruments in the Observatory. Stephen Charles Triboudet Demainbray (1710--1782) was the the first Royal Observer from 1769 to 1782. In 1772, a Harrison watch was tested here.

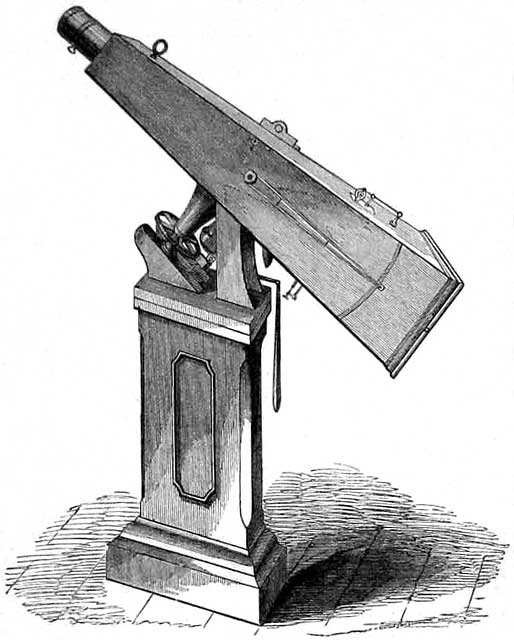

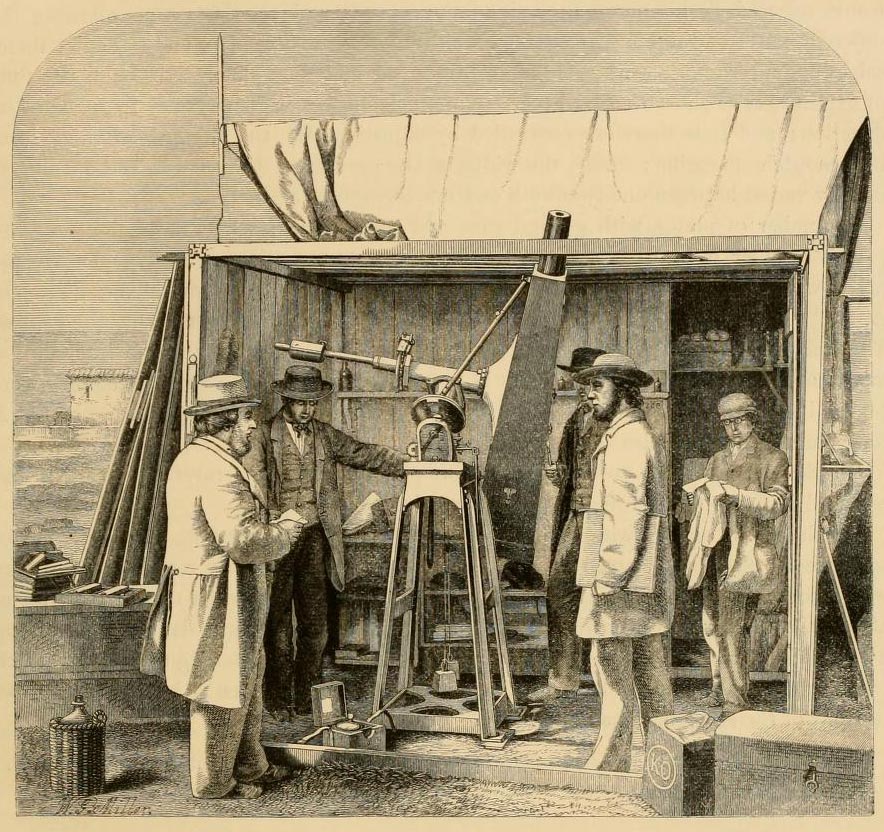

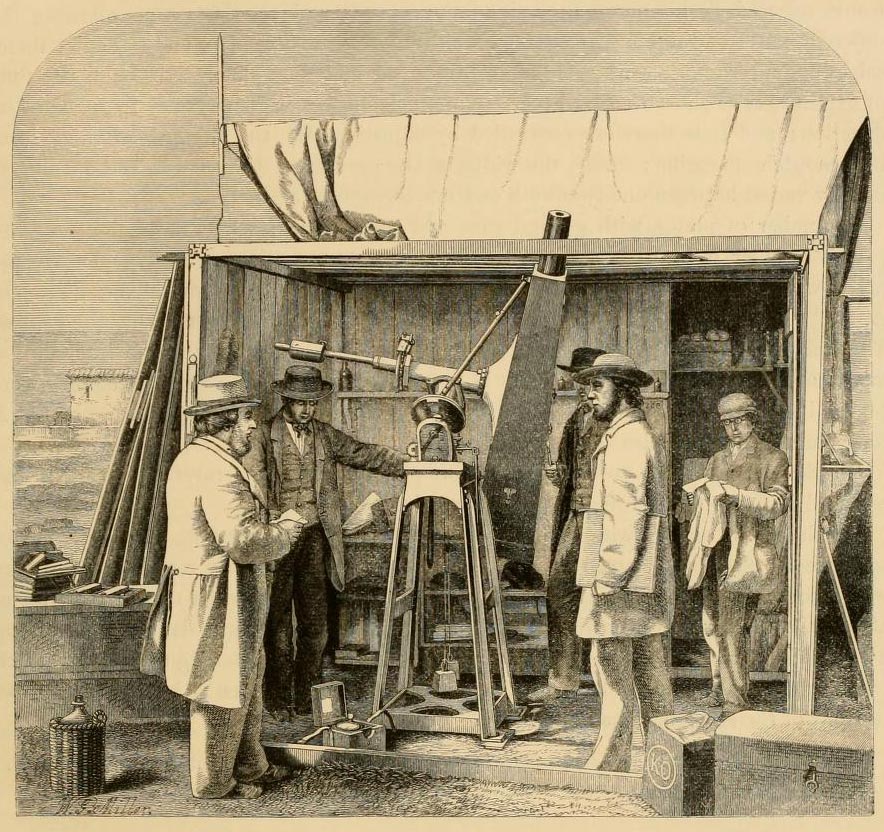

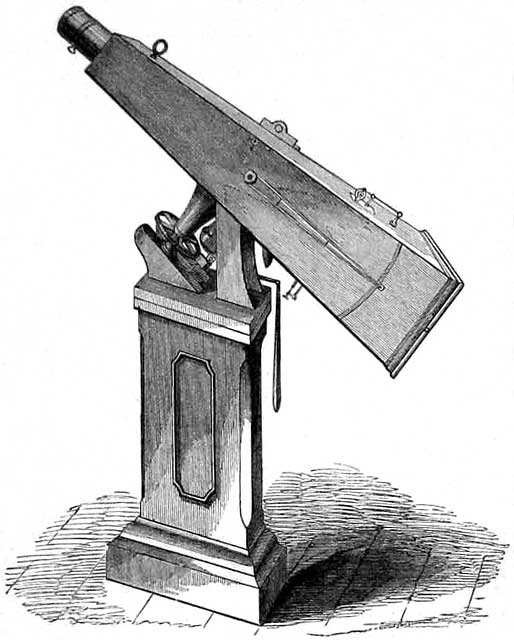

Fig. 3. Kew Photoheliograph, used by Warren de la Rue during the Total Solar Eclipse of July 18th, 1860, observed at Rivabellosa, Spain

(Warren de la Rue 1862, p. 31)

Fig. 3. Photo of the Sun during the Total Solar Eclipse, 1860 (Warren de la Rue 1862, plate)

With the Kew Photoheliograph, a pioneering instrument, invented by Warren de la Rue (1815--1889), made by A. Ross, London (1856), first light 1858, daily photographs of the Sun were made, between 1862 and 1872, a total of 1724 photographic plates; it continued until 1926.

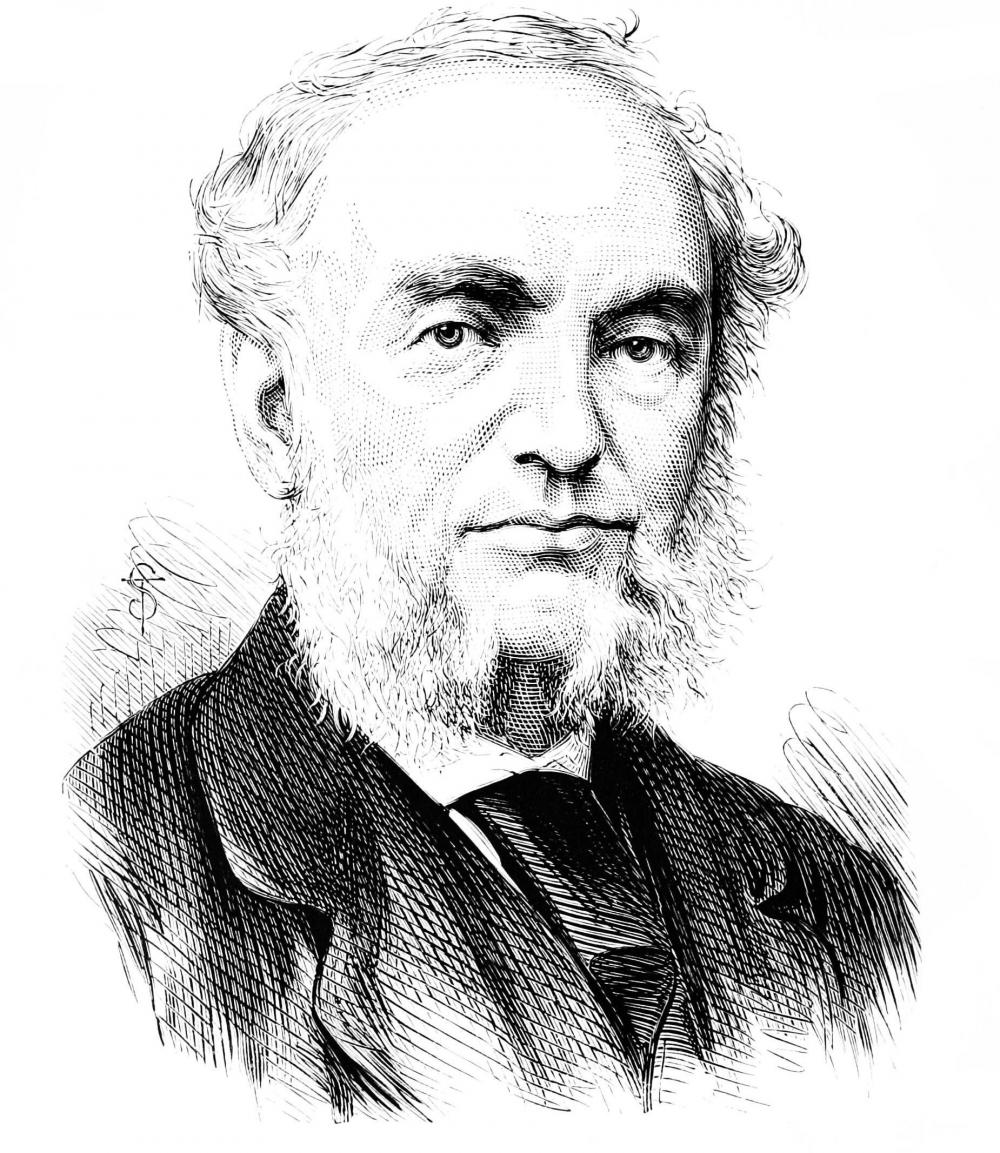

Balfour Stewart (1828--1887) noted in 1859 "magnetic disturbances of unusual violence and very wide extent" -- during the famous Carrington event, now known as an extremely bright Solar Flare. Already in 1851, Edward Sabine (1788--1883) had established a correlation between sunspots and magnetic storms.

Kew Observatory is an astronomical and terrestrial magnetic observatory; it was important for solar physics (the Kew Photoheliograph), meteorology, geomagnetism, and standardization (quality control of instruments, verification of sextants; they got a Kew’s hallmark). It was used for meteorological observations from 1773 to 1867; for geomagnetic measurements from 1842 to 1925; then it was too close to the electric train station. Also seismology was done there. Since 1923, meteorology used balloon, an early meteorological kite, later satellite and rockets in order to study the upper atmosphere.

Kew Observatory became one of the most important meteorological and geomagnetic observatories in the world. Kew’s electric and magnetic observatory made qualitiy control and verification of scientific instruments, and influenced the magnetic instruments e.g., of the East India Company Observatory Colaba near Bombay, Toronto, Stoneyhurst College, Lancashire, and Madrid Observatory (1790 to 1846).

It is a pity that the observatory was closed in 1841; a larger part of the George III’s collections of instruments were moved Armagh Observatory, and to King’s College in London, and are since 1926 in the Science Museum in London (Morton & Wess, 1993). The observatory was handed over to the British Association for the Advancement of Science from 1842 to 1871, then to the Royal Society as Kew Observatory. Since 1910 it is used as a Meteorological Office.

History

Fig. 4a. Kew Photoheliograph (The Engineer (23 Feb 1866), p. 137)

Fig. 4b. Warren de la Rue (1815--1889), albumen print, 1855 (Creative Commons 3.0)

Instruments

- Achromatic telescope (2.4m focal length)

- Achromatic telescope (smaller)

- Two reflecting telescopes: 4-inch-Gregorian and 6-inch-Reflector (61cm focal length),

made by Thomas Short of London (1769) -- donated by Queen Victoria to Armagh Observatory - Clock, Benjamin Vulliamy, clock-maker to the King

- Four clocks sold in 1916

- Transit instrument

- Positional astronomy instruments

- Photoheliograph, Warren de la Rue (1815--1889), made by A. Ross, London (1854/56), first light 1858

Fig. 4c. Short 6-inch-Reflector of King’s Observatory, used for the Venus Transit in 1869 -- now in Armagh Observatory (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt in Armagh)

Fig. 4d. Short 6-inch-Reflector of King’s Observatory, signature (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt in Armagh)

Fig. 4e. Short-4-inch-Gregorian of King’s Observatory, used for the Venus Transit in 1869 --

now in Armagh Observatory (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt in Armagh)

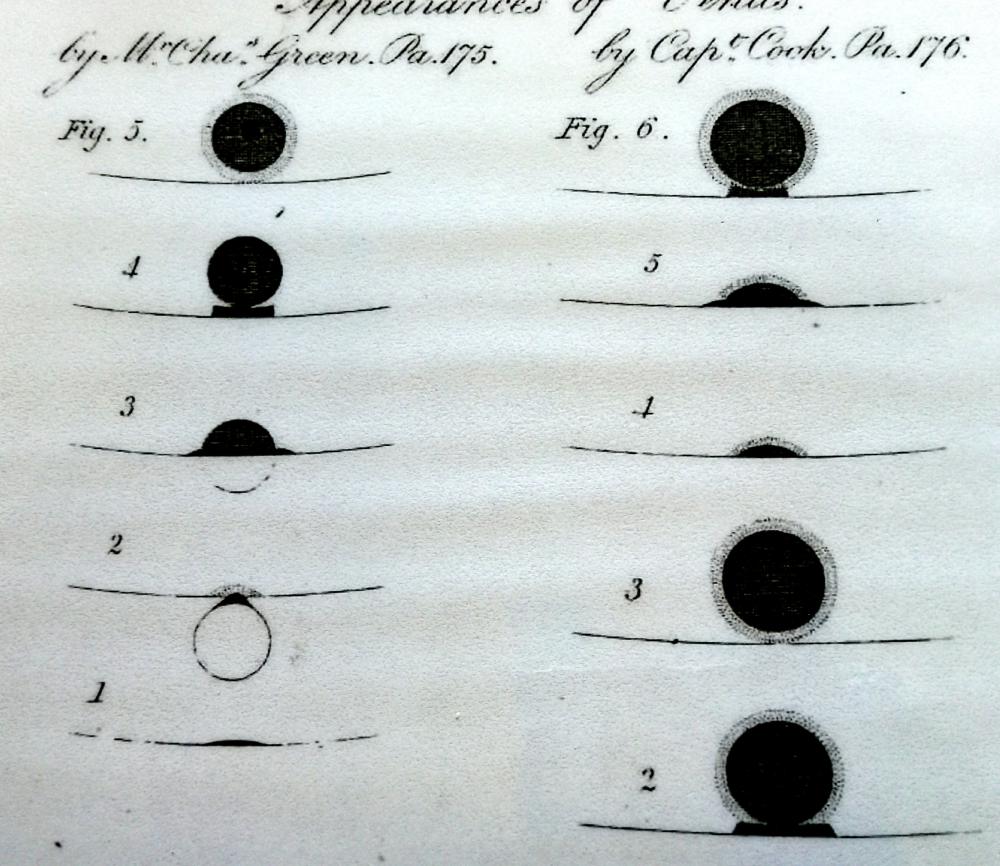

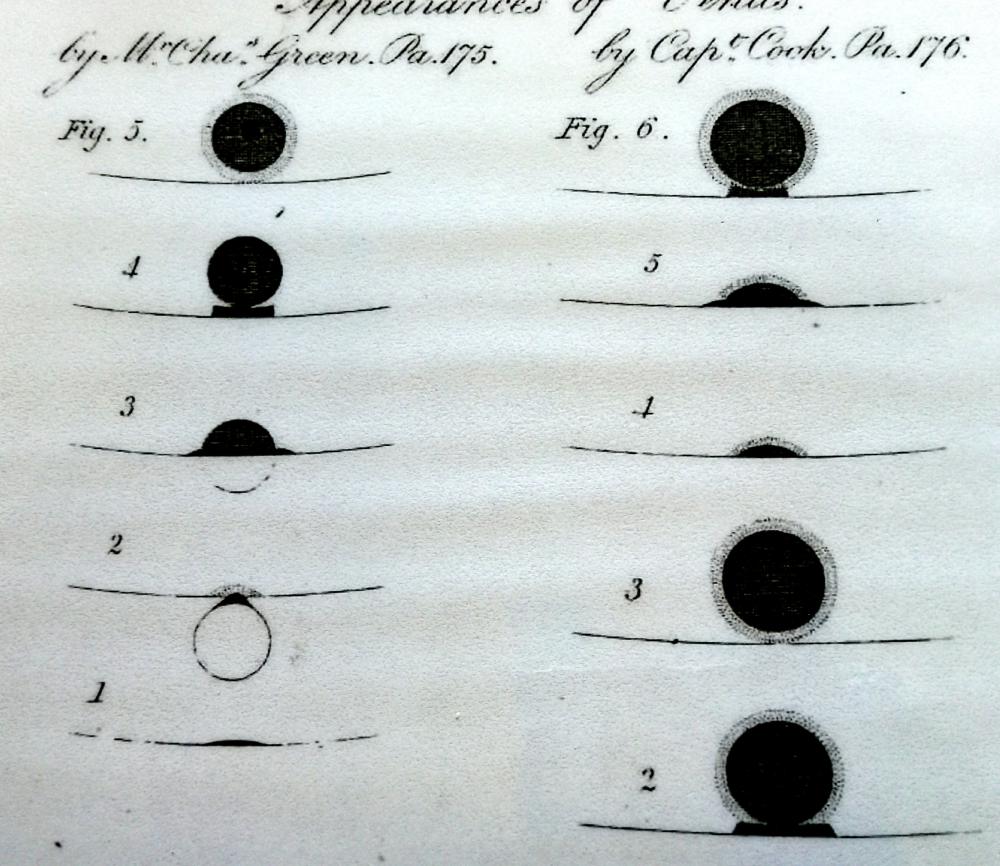

Fig. 4e. Transit of Venus (1769), (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 5. Kew’s hallmark for quality control of instruments, e.g. thermometers (1889)

- Meteorological instruments:

Thermometer, Thermograph, Barometer,

Hygrometer, Rain gauge, Ozonometer,

Anemometer, Anemograph, Sunshine recorder,

Electrograph -- measuring atmospheric electricity,

Thomson electrometer with photographic self registration - Dip-circle, Dip needle

- Inclinometer

- Declinometer

- Unifilar / Bifilar Magnetometers

- Horizontal force Magnetograph (self recording)

- Vertical force Magnetograph (self recording)

Fig. 6. Balfour Stewart (1828--1887) (Wikipedia)

Directors of King’s Observatory / Kew Observatory

- Stephen Charles Triboudet Demainbray (1710--1782), 1768 to 1782

- Francis Ronalds (1788--1873), 1842 to 1853

- John Welsh (1824--1859), 1853 to 1859

- Balfour Stewart (1828--1887), 1859 to 1887

- Charles Chree (1860--1928), 1893 to 1925

- Francis John Welsh Whipple (1876--1943), 1925 to 1939

- George Clarke Simpson (1878--1965), 1939 to 1947.

State of preservation

Fig. 7. King’s Observatory, William Chambers (1769) (courtesy of The King’s Observatory)

Kew Observatory is preserved well; it is a Grade I listed building (1357729) since 1950:

Designed by Sir William Chambers. Built 1768-69 when Dr Stephen Demainbray, a tutor to the royal family, persuaded George III to take an interest in a transit of Venus. Chambers conceived the design in terms of a small villa with canted bays on the northand south fronts creating a pair of conjoined octagonal rooms on one axis. Apart from the raising of the side roofs to the level ofthe observing chamber sometime after 1884 the building remains unaltered. Three storeys, including basement. Stuccoed. Five windows wide; staircase either side of first floor entrance. Basement rusticated. Cornices above first and second floors. Balustraded parapet. Square headed, moulded windows, some pedimented. Dome to roof, carrying observatory equipment.

The former famous observatory is now a private dwelling.

Comparison with related/similar sites

Fig. 7. King’s Observatory with the dome at night (1769) (courtesy of The King’s Observatory)

Kew Observatory is a one dome observatory of the 18th century; it has the earliest moveable dome known in architectural history.

Kew Observatory influenced the architecture of the two Irish observatories, Armagh Observatory (1790) and Dunsink Observatory Dublin (1785).

Fig. 8b. King’s Observatory with the earliest preserved observatory dome (© John Butler)

Fig. 8c. King’s Observatory -- inside of this early preserved dome (© John Butler)

Threats or potential threats

no threats

Present use

Fig. 9. King’s Observatory today (© John Butler)

Since 1910 it is used as a Meteorological Office, but scientific use has stopped.

In 2015, the building was restored and it is now available for residential lease.

Astronomical relevance today

No astronomical use today; Kew is famous for the Kew Photoheliograph, a pioneering instrument,

which was used for the daily photographs of the Sun (until 1926), now in Science Museum (Inventory No.1927-0124).

References

Bibliography (books and published articles)

- Bryden, D.J.: Qualitiy Control in the Making of Scientific Instruments. Kew Observatory and the Verification of Meteorological, Magnetic and Other Instruments, 1851--1899. In: Bulletin of the Scientific Instrument Society (2006, No. 88, p. 48--59.)

- Harris, J.; Crook, J Mordaunt & Eileen Harris: Sir William Chambers Knight of the Polar Star. London: A. Zwemmer 1970.

- Lindsay, Eric M.: The Astronomical Instruments of H.M. King George III presented to Armagh Observatory. In: Irish Astronomical Journal 9 (1969), p. 57--68.

- Macdonald, Lee T.: Kew Observatory and the Evolution of

Victorian Science, 1840--1910. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press (Science and Culture in the Nineteenth Century) 2018. - Morton, Alan Q. & Jane A. Wess: Public and Private Science. The King George III Collection. Oxford University Press, Science Museum 1993.

- Ronalds, B.F.: "The Beginnings of Continuous Scientific Recording using Photography: Sir Francis Ronalds’ Contribution." In: European Society for the History of Photography (2016).

- Watkin, David: The Architect King: George III and the Culture of the Enlightenment. London: Royal Collection Publications 2004.

- De la Rue, Warren: On Celestial Photography. In: Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 19 (1859), pp. 353- 358.

- De la Rue, Warren: The Bakerian Lecture: On the Total Solar Eclipse of July 18th, 1860, Observed at Rivabellosa, Near Miranda de Ebro, in Spain. In: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society London 152 (1862), pp. 333--416.

Links to external sites

- ""The Observatory and Obelisks, Kew (Old Deer Park)". In: Local history notes. London Borough of Richmond upon Thames.

- The Kew Photoheliograph (1854). Royal Observatory Greenwich.

- Scientific Instruments of George III. In: Nature 163 (1949), 631.

- "Ronalds, Francis (DNB00)." In: Dictionary of National Biography, Vol. 49 (1885--1900).

- Balfour Stewart. In: Fellows Directory. Biographical Index: Former Royal Society of Edinburgh (RSE) Fellows 1783--2002.

Links to external on-line pictures

Images - courtesy of

No multimedia content published

Currently there is no multimedia content published for this case study