Category of Astronomical Heritage: tangible immovable

Lilienthal Observatory, Germany

Description

Geographical position

Lilienthal Observatory, Lilienthal (near Bremen), Lower Saxony (not Schleswig-Holstein),

on the other side of Borgfelder Landhaus, crossing of Hauptstrasse and Warfer Landstrasse

Location

Lat. 53° 8′ 28.2984″ N, long. 8° 54′ 45.3996″ E, elevation 6m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code

280

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage

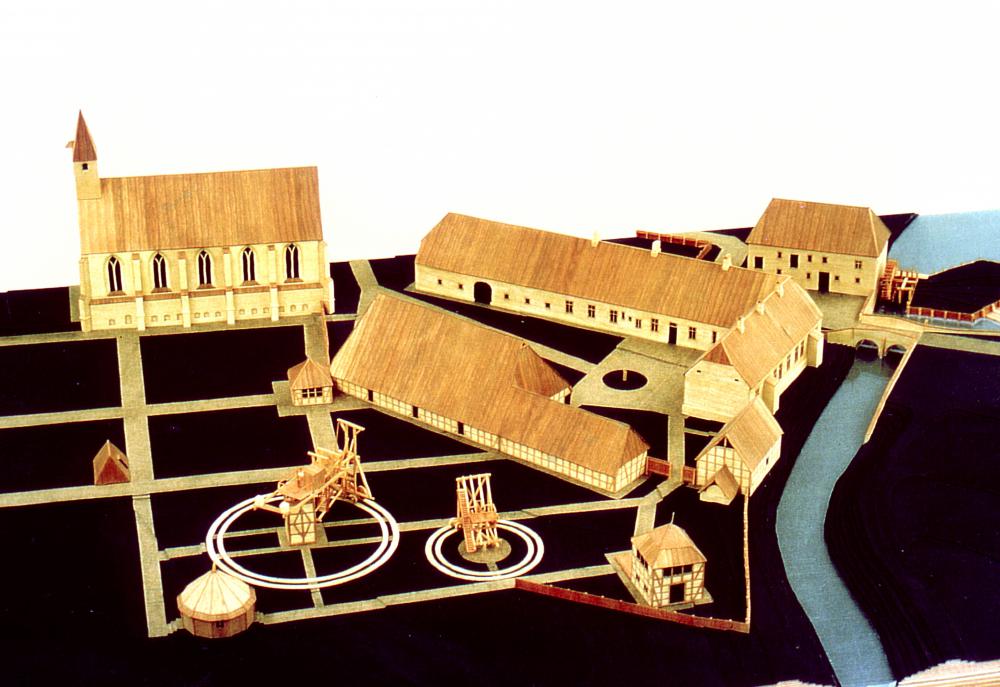

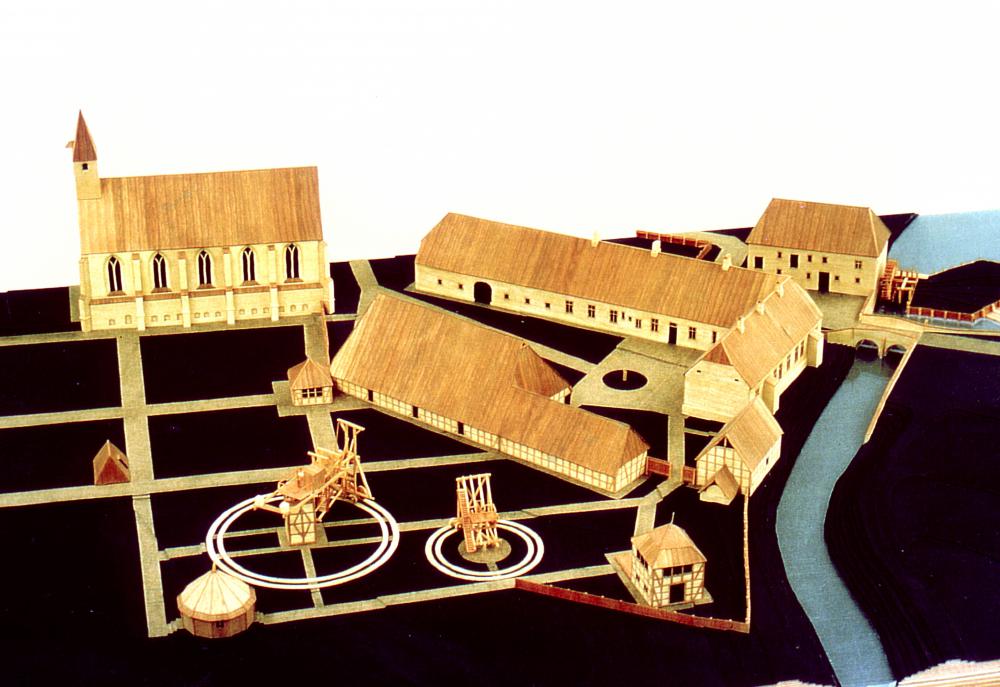

Fig. 1. Model of the observatories in Lilienthal, made by Felix Lühning, Berlin

Johann Hieronymus Schröter (1745–1816) built an impressive observatory with a giant 20-inch-telescope - it was the best equipped observatory on the continent, only surpassed by William Herschel’s (1738–1822) telescope.

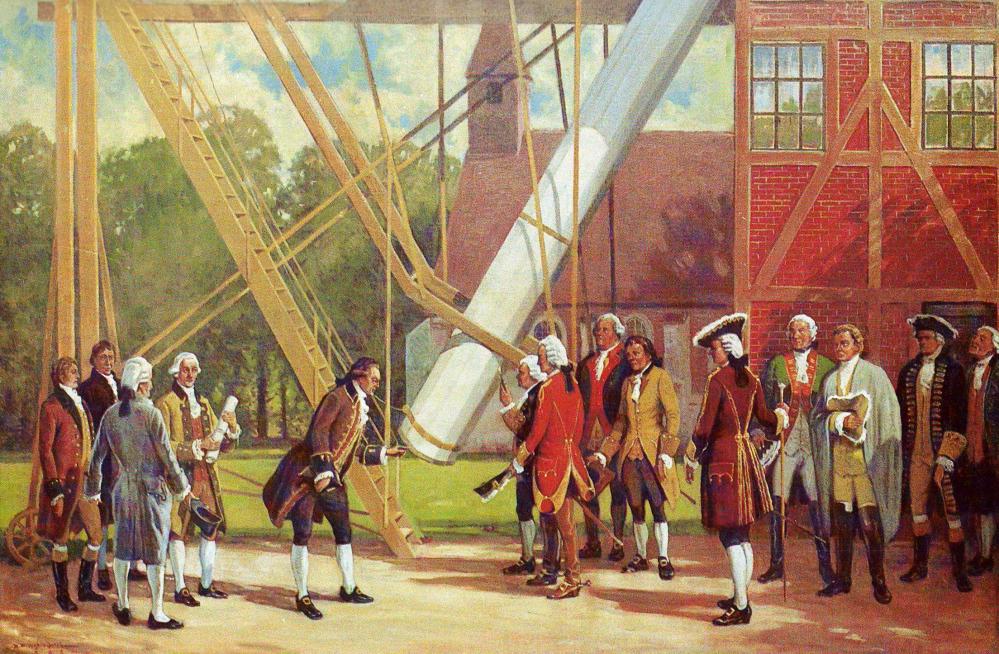

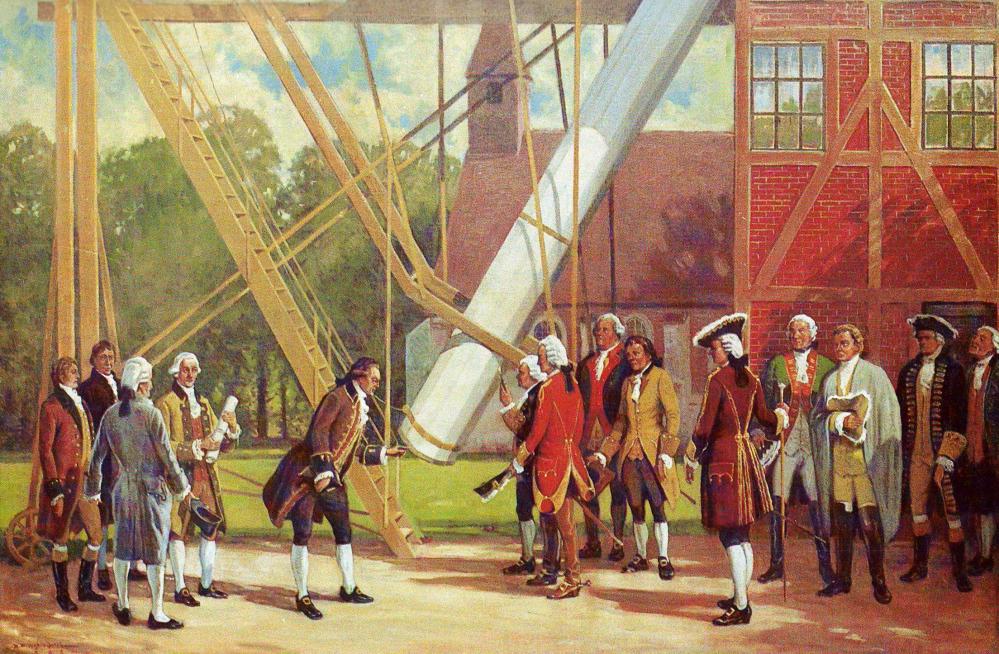

Fig. 2. Schröter presents his telescope for the visit of Prince Adolph Friedrich in 1800 - Painting: H.W. Vogt-Vilseck (1903-1996), 1988

Lilienthal became known worldwide not only because of the telescope but also because of the foundation of the "Vereinigte Astronomische Gesellschaft" (VAG, United Astronomical Society) in 1800. A group around Schroeter, Wilhelm Olbers (1758–1840) together with Franz Xaver von Zach (1754–1832) founded this astronomy association, the so-called "Himmelspolizey" (celestial police) in order to find the missing planet between Mars and Jupiter. The astronomy association had 24 top-ranking astronomers in Europe—two for each constellation. Each astronomer should search a segment of the ecliptic that was 15 degrees wide and extended about 7.5 degrees above and below the ecliptic. Schröter was elected as president of the VAG, Zach as secretary. The highlight of the founding meeting in Lilienthal (1800), however, was the visit of Prince Adolph Friedrich, son of King George III of England and Hanover, who later became governor-general and viceroy of the Hanoverian Lands. In the following years the members of this association found not only one planet but several asteroids, as they have become known since. The seal of the Lilienthal "United Astronomical Society" (VAG), founded on September 20, 1800, contains the motto Non frustra signorum obitus speculamur et ortus (We do not vainly observe the ascents and descents of the signs of the zodiac) (1802).

Fig. 3. Logo of the "Vereinigte Astronomische Gesellschaft" (VAG, United Astronomical Society), founded in 1800 in Lilienthal (Lilienthalsche Beobachtungen der neu entdeckten Planeten CERES, PALLAS und JUNO. Göttingen: Vandenhoek und Ruprecht 1805)

Half of the 24 founding members of the VAG were from non-German-speaking countries. Denmark, Sweden, Russia, France, England, and Italy were together as strongly represented as the ’German’ States, and three members came from the Habsburg lands (Vienna, Krakow, and Milan). They were:

- GERMAN States (11): Johann Hieronymus Schroeter (Lilienthal), Franz Xaver von Zach (Gotha), Karl Ludwig Harding (Lilienthal), Wilhelm Olbers (Bremen), Johann Gildemeister (1753-1837) (Bremen), Ferdinand Adolf Freiherr von Ende (1760-1816) (Celle), Johann Elert Bode (1747–1826) (Berlin), Prof. Johann Siegismund Gottfried Huth (1763-1818) (Frankfurt/Oder), Georg Simon Klügel (1739-1812) (Halle), Johann Friedrich Wurm (1760-1833) (Tübingen), Dr. Julius August Koch (1752-1817) (Danzig),

- HABSBURG Lands (3): Joseph Tobias Bürg (1766-1834) (Wien), Prof. Johann Sniadecki (1756-1830) (Krakau), Barnaba Oriani (1752-1832) (Milan),

- DENMARK (1): Thomas Bugge (1740-1815) (Copenhagen),

- SWEDEN (2): Prof. Daniel Melanderhielm (Stockholm) (1726-1810), Prof. Jöns Svanberg (1771-1851) (Uppsala),

- ENGLAND (2): William Herschel (1738-1822) (Slough), Nevil Maskelyne (1732-1811) (Greenwich),

- FRANCE (4): Pierre Méchain (1744-1804) (Paris), Charles Messier (1730-1817) (Paris), Johann Karl [Jean Charles] Burckhardt (1773-1825) (Paris), Jacques Thulis (1748-1810) (Marseille),

- ITALY (1): Giuseppe [Joseph] Piazzi (1746-1826) (Palermo),

- RUSSIA (1): Kollegienrath Friedrich Theodor von Schubert (1758-1825) (St. Petersburg).

Carl Friedrich Gauß (1777–1855), Braunschweig, became a member in 1801.

History

Johann Hieronymus Schröter (1745-1816) started studying theology in Erfurt in 1762, and later he studied law in Göttingen (finished in 1767), but all the time he also studied and practised astronomy. In Hannover he met members of the Herschel family and acquired his first telescope, a 3-foot Dollond achromatic refractor, in 1779, for observing the sun. Inspired by Herschel’s discovery of Uranus (1781), he started intensive observations.

Fig. 4. Johann Hieronymus Schröter (1745-1816)

In 1782, Johann Hieronymus Schröter became chief magistrate ("Amtmann") in Lilienthal. In addition to this administrative office, he also played an important role in promoting astronomy during his lifetime. In 1784 he built a first powerful reflector telescope with 12cm aperture and 4-foot (122cm) focal length. The mirror and eight eyepieces had been sent to him by William Herschel from England. Schröter named his observatory "Uranienlust" (1785), inspired by Tycho’s Uraniborg; it had a diameter of 5.1m. In 1786 he got further components from Herschel, which he used for another reflecting telescope with 16.5cm aperture and 7-foot (2.14m) focal length (1788).

Fig. 5a. Replica of Schröter’s 27 foot reflecting telescope (1793), 2015 (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 5b. Replica of Schröter’s 27 foot reflecting telescope (1793), 2015 (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Together with Johann Gottlieb Friedrich Schrader (1763-1833), professor for physics and chemistry, Schröter made experiments to construct reflecting telescopes of Newton type like William Herschel. Especially they tried to find a perfect whitish, brittle alloy of copper and tin, which they mixed with some arsenic. To increase the reflectivity, they vaporized an additional layer of arsenic. With this method they got telescopes with very good reflectivity. They made several 7-foot, 12-foot, and 13-foot telescopes, as well as the first mirror for the 27-foot large telescope. Schrader has made for himself the mirror of a 26-foot telescope, which he installed in 1794 in Kiel.

In the following years, Lilienthal Observatory was one of the best equipped observatories in the world with about ten telescopes.

In 1793 Schröter constructed his large two-storey observatory with 20m diameter and 8m height. His technological highlight was the "Riesenteleskop" (giant telescope) in 1793, a reflecting telescope with a 50cm (20 inch) aperture and 27 Hanover foot (7.9m) focal length. The telescope had a sophisticated azimuthal mounting.

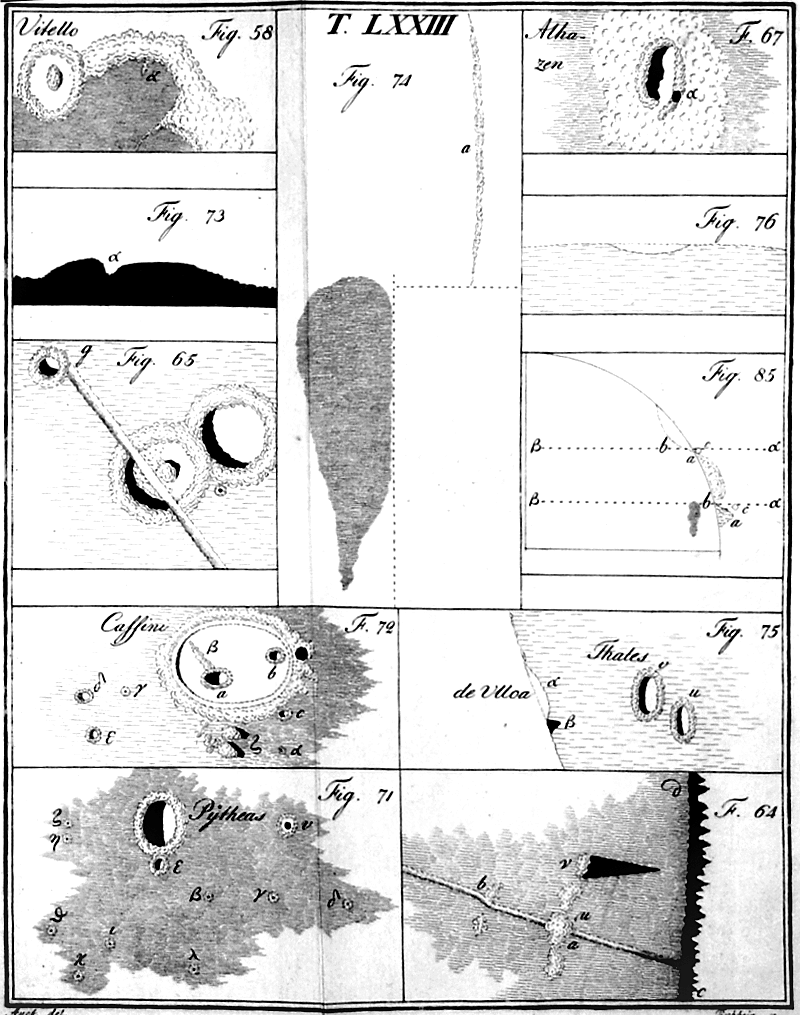

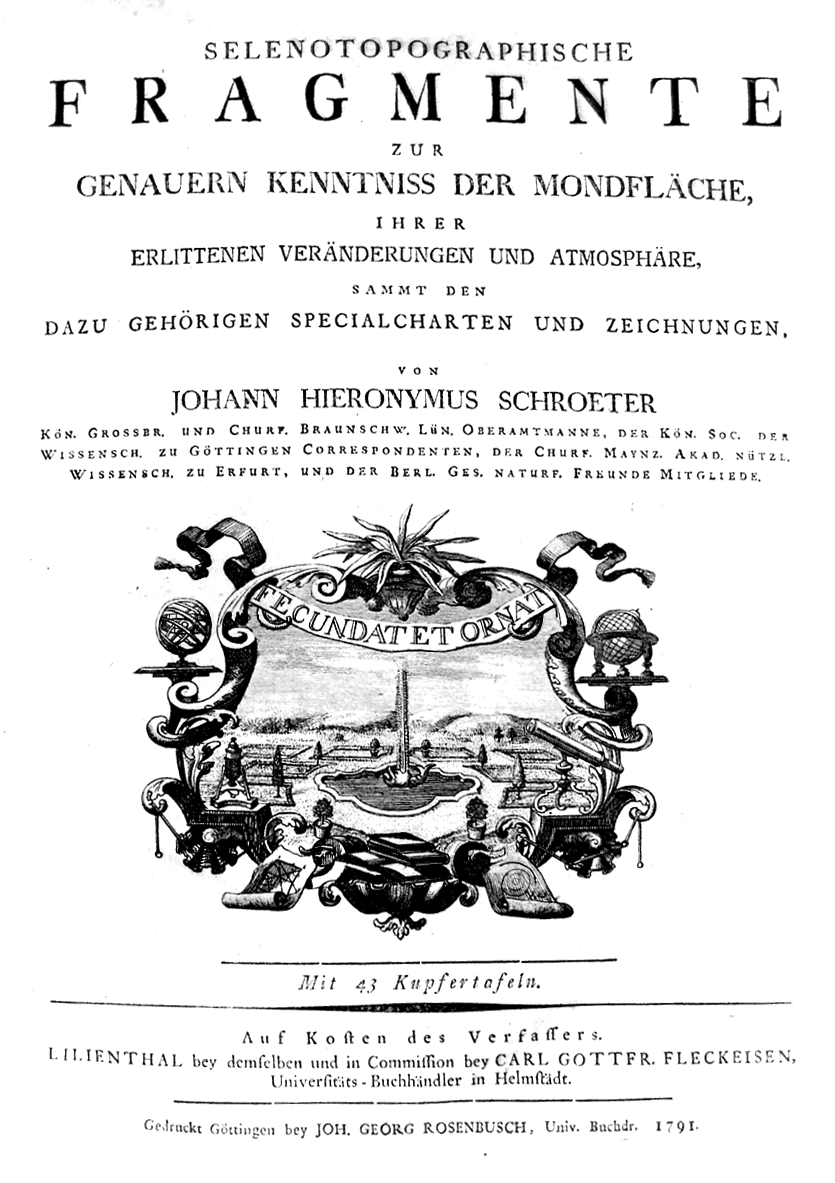

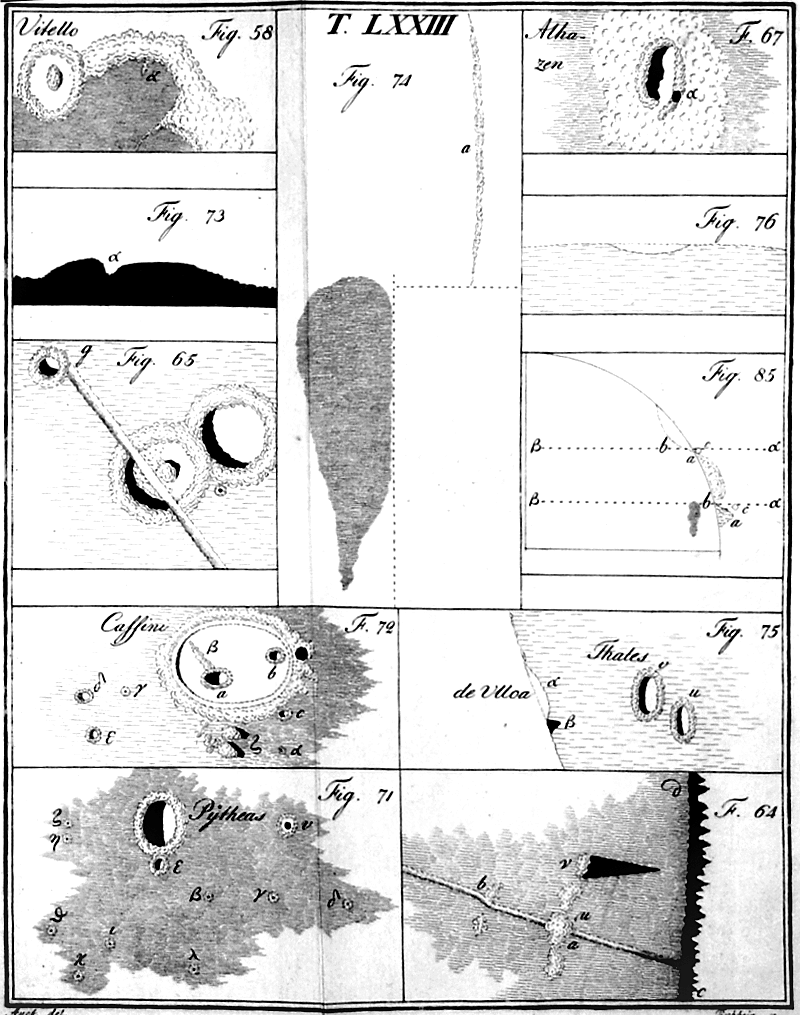

Schröter used his telescopes for observing planets, especially Venus, and studied the moon in detail; his cartography appeared as "Selenotopographische Fragmente" (1791-1802). In 1787 he was accepted as a member of the Erfurt and Göttingen Academies.

Due to this 27 foot telescope, Lilienthal became well-known and was contacted in matters of astronomy by government and military officials. Schröter stayed in contact with many of the important astronomers of the time. Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel got his first astronomical education and introduction there.

In 1795 Schröter built a third observatory, the "Urania-Tempel", for his 10 foot Dollond refractor, parallactically mounted. The Urania-Temple of 7m diameter looked like a nowadays observatory; instead of a dome there were 8 flaps, which could be opened separately and offered a window of 45’. Finally in 1807 he added another large 20 foot reflecting telescope of 31cm aperture.

Fig. 6a. Replica of Schröter’s 27 foot reflecting telescope (1793), 2015 (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 6b. Replica of Schröter’s 27 foot reflecting telescope (1793), 2015 (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Together with Wilhelm Olbers (1758-1840), who had a private observatory in Bremen, and other scholars, Schroeter founded the "Vereinigte Astronomische Gesellschaft" (astronomy association) in Lilienthal in 1800. The third asteroid Juno was discovered in 1804 by the observator Karl Ludwig Harding (1765-1834) at the Observatory, since 1805 professor in Göttingen university. Olbers discovered the second asteroid Pallas in 1802, and the fourth asteroid Vesta in 1807.

In 1799, Schroeter’s salary as senior official no longer sufficed for the maintenance of the observatory and the costs of its publications. Therefore he sold all the equipment to the English-Hanoverian King George III. (1738-1820). The instruments remained in Lilienthal. Schroeter received 1200 English guineas (today’s value about 150,000 euros), a pension of 300 talers and 200 talers to pay an "observatory inspector". After Schroeter’s death, the devices had to be presented to the University of Göttingen.

The Napoleonic War of Liberation in 1813 damaged Lilienthal severly, but the observatory was not burned down. But after Schröter’s death in 1816, the observatory fell into disrepair. In 1850 the remaining structure was destroyed. A large part of instruments and papers of Lilienthal observatory was sent to the University of Göttingen before the demolition.

The writer Arno Schmidt (1914-1979) planned a novel about the Lilienthal astronomers, which did not get ready. In his novel "Kaff", published in 1960, Schmidt also used part of the collected material for Mare Crisium, who plays in a "Kaff" (small village) in the Lüneburg Heath as well as on the Moon, in the area of Mare Crisium. Schmidt’s remaining designs of this Lilienthal novel were published in 1996 from the estate.

Fig. 7. Schröter’s Selenotopographische Fragmente (1791-1802)

Fig. 8. Schröter’s Selenotopographische Fragmente (1791-1802)

Fig. 9. A model of the four orbits of the asteroids was produced by J.E. Bode, Babelsberg observatory (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

State of preservation

Only some smaller instruments are preserved in the University of Göttingen. The second mirror, made for the 27-foot telescope in Lilienthal, is now in the Deutsches Museum in Munich.

Comparison with related/similar sites

This Lilienthal Observatory, organized by Johann Hieronymus Schroeter (1745--1816), was a unique place of telescope making and research.

The result, 27-ft reflecting telescope, was the largest telescope on the continent.

Schroeter’s large reflecting telescopes are only comparable with those of Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel ( 1738--1822).

Threats or potential threats

No threats, protected and activly used by TELESCOPIUM Lilienthal. The "Astronomische Vereinigung Lilienthal" (AVL), Working Group "TELESCOPIUM" provides historical information, and offers star gazing with the historical telescope.

Present use

A replica of Schroeter’s 27-ft reflecting telescope from 1794 in Lilienthal was made by Klaus-Dieter Uhden, and inaugurated in Nov. 2015; this telescope with a modern mirror, but all the old mounting and layout are constructed like in the case of the original telescope.

It is used as public observatory; the star gazing is organized by the Astronomical Association Lilienthal "Astronomische Vereinigung Lilienthal" (AVL), Working Group "TELESCOPIUM". One can also study historical observation methods.

Fig. 10a. Replica of Schröter’s 27 foot reflecting telescope (1793), 2015 (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 10b. Replica of Schröter’s 27 foot reflecting telescope (1793), 2015 (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 11. Replica of Schröter’s 27 foot reflecting telescope (1793), 2015 (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12a. Replica of Schröter’s 27 foot reflecting telescope (1793), 2015 (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Fig. 12b. Replica of Schröter’s 27 foot reflecting telescope (1793), 2015 (Photo: Gudrun Wolfschmidt)

Astronomical relevance today

No relevance for modern astronomy, but active in the history of astronomy. The TELESCOPIUM Lilienthal, .

References

Bibliography (books and published articles)

- Gerdes, Dieter: Die Geschichte der Astronomischen Gesellschaft. Heimatverein Lilienthal [1990].

- Gerdes, Dieter: Die Lilienthaler Sternwarte 1781 bis 1818. Machinae Coelestes Lilienthalienses. Die Instrumente. Eine zeitgeschichtliche Dokumentation.Lilienthal: Verlag M. Simmering 1991.

- Drews, Jörg & Heinrich Schwier (Hg.): "Lilienthal oder die Astronomen". Historische Materialien zu einem Projekt Arno Schmidts. Edition Text + Kritik. München 1984.

- Finkenzeller, U.: Sterne und Wortraum Arno Schmidts. Hintergründe zur Namensgebung des Kleinplaneten (12211) Arnoschmidt). In: Sterne und Weltraum (2007), Heft 8, p. 48-54

- Leue, Hans-Joachim: Neues vom Telescop(ium). In: Himmelspolizey 45 (Januar 2016), S. 4-8.

(https://www.avl-lilienthal.de/files/AVL/pdf/hipo2015_03.pdf)

- Lühning, Felix: Schrader, Johann Gottlieb Friedrich. In: Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB), Band 23. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot 2007, p. 510.

- Schroeter, Johann Hieronymus: Selenotopographische Fragmente Zur Genauern Kenntniss Der Mondfläche, Ihrer Erlittenen Veränderungen Und Atmosphäre, Sammt Den Dazu Gehörigen Specialcharten [...]. Lilienthal: Auf Kosten des Verfassers: bey demselben und in Commission bey Carl Cottfr. Fleckeineisen, Universitäts-Buchhändler in Helmstädt: in Commission der Vandenhoeck- und Ruprechtischen Buchhandlung; Göttingen: Grdruckt bey Joh. Georg Rosenbusch, Univ. Buchdr.: Gedr. in der Barmeierischen Universit. Buchdruckerey, 1791-1802.

- Schumacher, Hermann A .: Die Lilienthaler Sternwarte. Ein Bild aus der Geschichte der Himmelskunde in Deutschland. In: Festschrift zur Feier des fünfundzwanzigjährigen Bestehens des Naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins zu Bremen, 1889, S. 39-170. (https://archive.org/stream/abhandlungenhera11natu#page/38/mode/2up)

- Voigt, Hans-Heinrich: Hieronymus Schroeter - Lilienthal - Astronomische Gesellschaft. In: Sterne und Weltraum 12/2000, p. 1040-1047.

- Witt, Volker: Erinnerungen an die Sternwarte Lilienthal. In: Sterne und Weltraum (2006), Heft 12, p. 84-93.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Die Bedeutung der Mädlerschen Mondkarten in der Entwicklung der Mondtopographie. In: Wissenschaftliches Jahrbuch des Deutschen Museums, München (Abhandlungen und Berichte N.F. 7) 1990, S. 132-154, p. 156-158.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: ,,Internationalität von der VAG (1800) bis zur Astronomischen Gesellschaft.’’ In: Dick, Wolfgang R. und Jürgen Hamel (Hg.): Astronomie von Olbers bis Schwarzschild. Nationale Entwicklungen und Internationale Beziehungen im 19. Jahrhundert. Frankfurt am Main: Harri Deutsch (Acta Historica Astronomiae Vol. 14) 2002, p. 182-203.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Mondtopographie und Längengrad. In: Tobias-Mayer-Symposium anläßlich des 250. Todestages von Tobias Mayer. Hg. von Erhard Anthes und Armin Hüttermann. Leipzig: AVA - Akademische Verlagsanstalt (Acta Historica Astronomiae, Band 48) 2013, p. 161-210.

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Astronomy and History of Science in European Context - a Network for Edutainment. Proceedings of the 1st European IHPST Regional Conference, Flensburg, 22.--25. August 2016, Science as Culture in the European Context: Historical, Philosophical, and Educational Perspectives. In: Science & Education (2019), p. 109-123. (ISBN 978-3-939858-39-3).

- Wolfschmidt, Gudrun: Internationalität in der astronomischen Forschung vom 17. bis zum 21. Jahrhundert. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (Hg.): Internationalität in der astronomischen Forschung (18. bis 21. Jahrhundert). Proceedings der Tagung des Arbeitskreises Astronomiegeschichte in der Astronomischen Gesellschaft in Wien 2018. Hamburg: tredition 2020, S. 22-115.

Links to external sites

TELESCOPIUM Lilienthal

Astronomische Vereinigung Lilienthal e.V. (AVL)

Astronomische Stätten in Lilienthal

No multimedia content published

Currently there is no multimedia content published for this case study