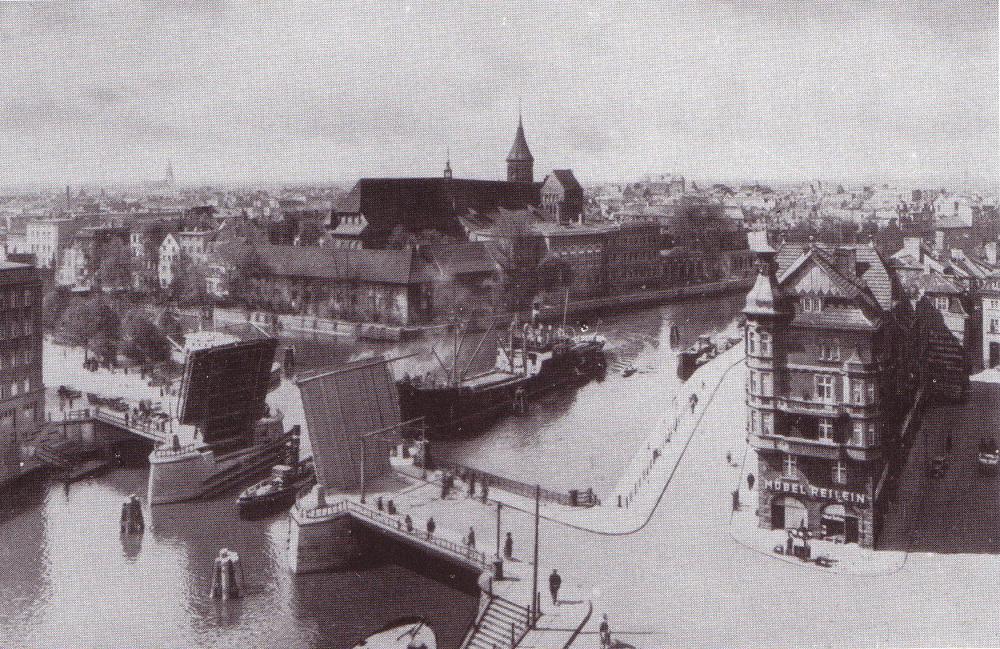

Category of Astronomical Heritage: tangible immovable

Königsberg Observatory, Russia

Description

Geographical position

Astronomical Bastion in Kaliningrad, place near Königsberg Observatory (1810 to 1945), Königsberg, Prussia, today Kaliningrad, Russia

Location

Lat. 54° 42′ 47.0016″ N, long. 20° 29′ 39.9984″ E, elevation 16m above mean sea level.

IAU observatory code

058

Description of (scientific/cultural/natural) heritage

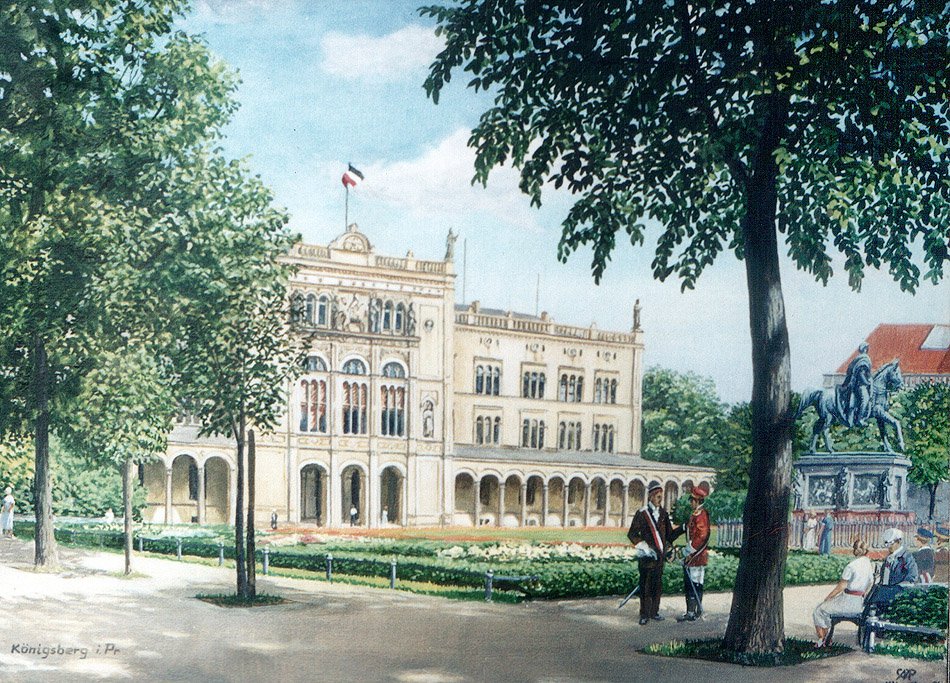

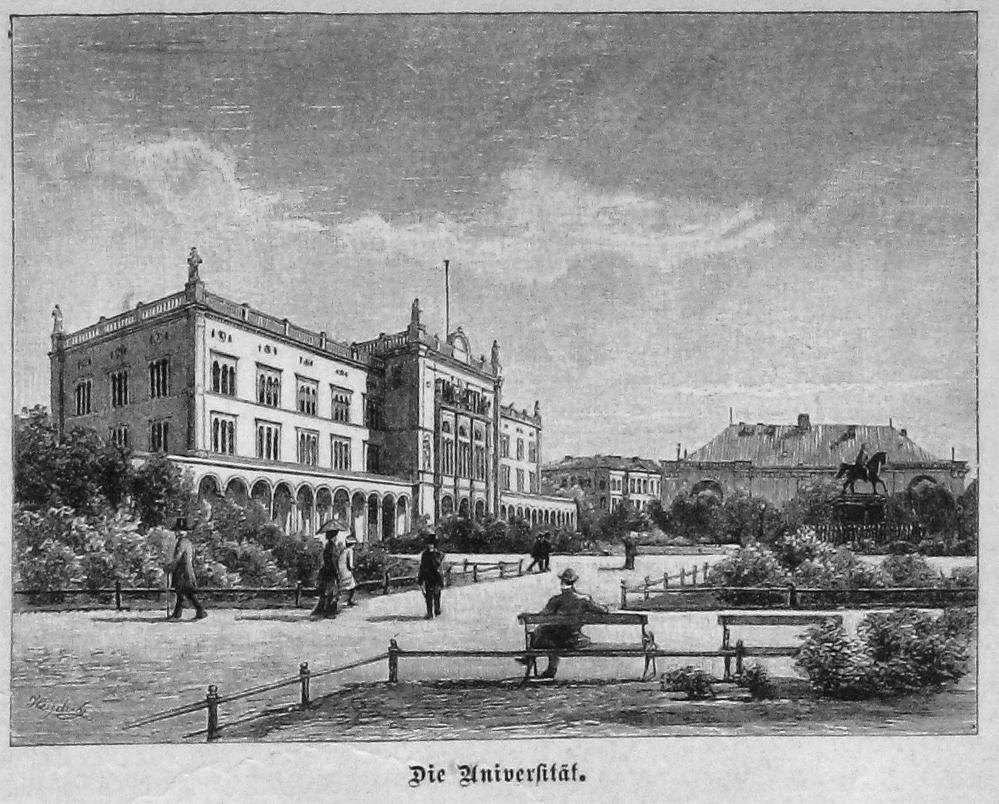

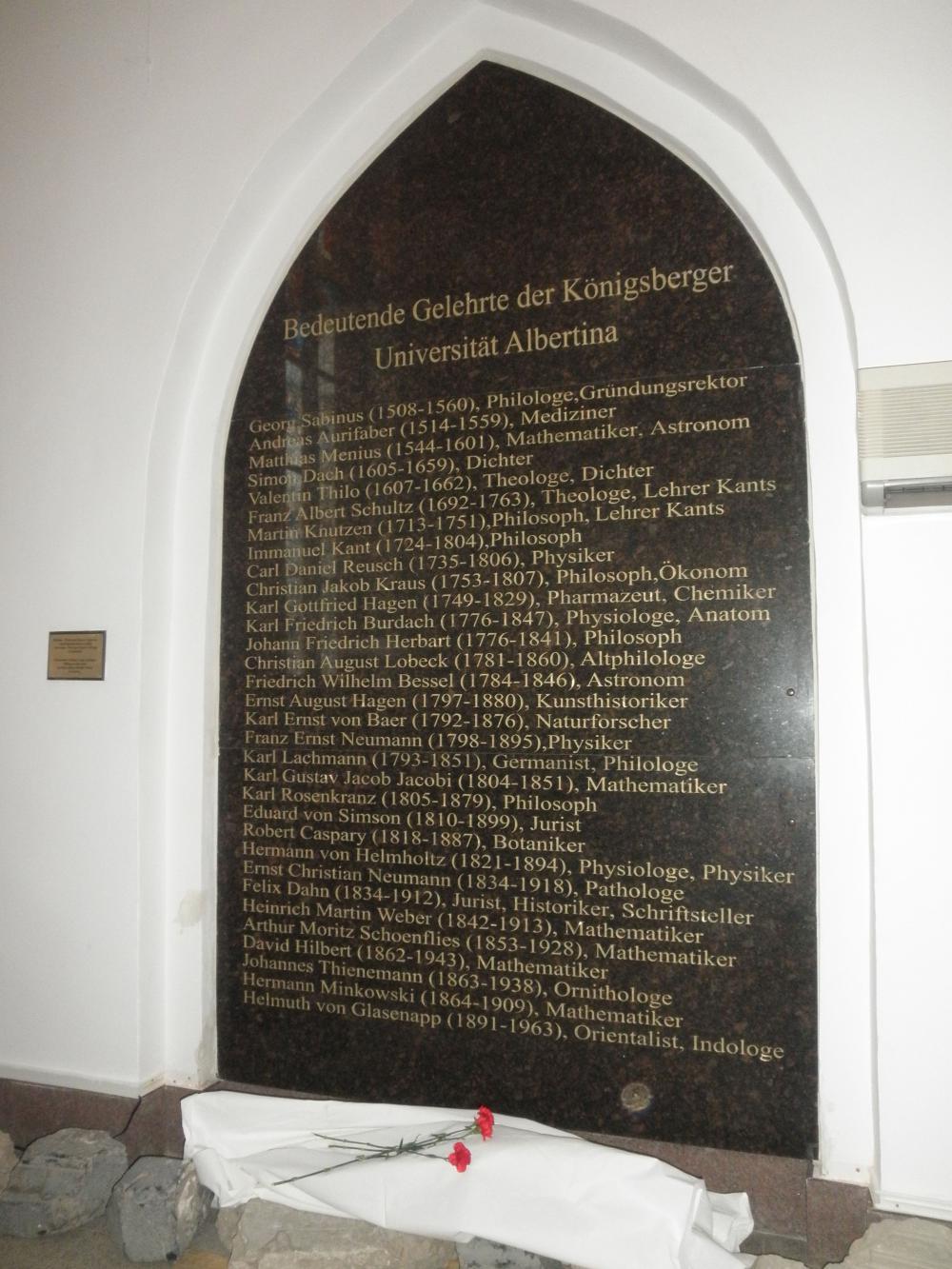

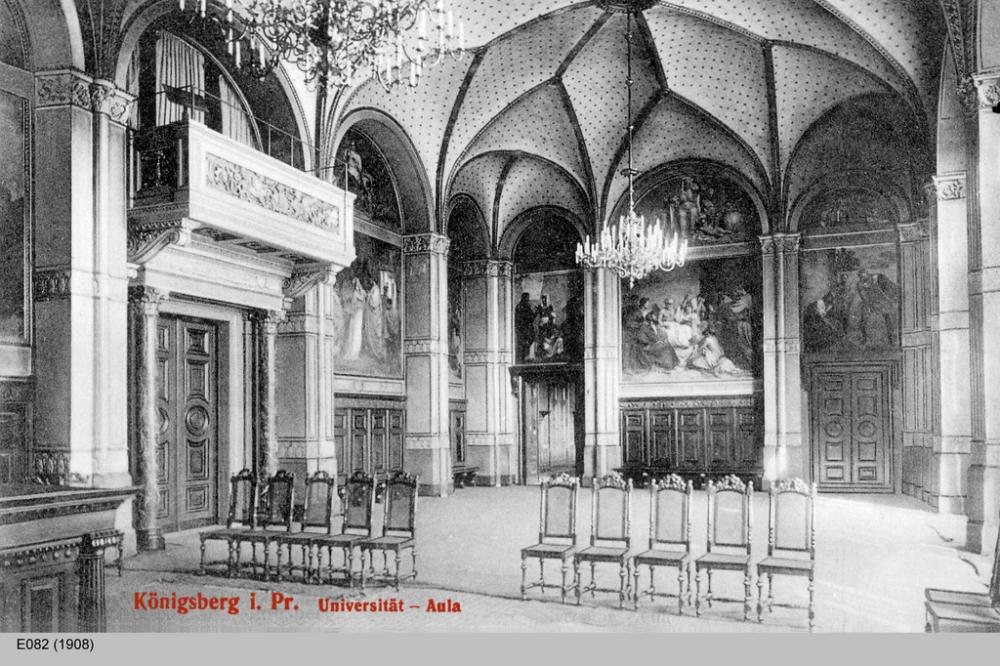

Fig. 1a. Königsberg University Albertina, new main building (1844/62), (creative commons)

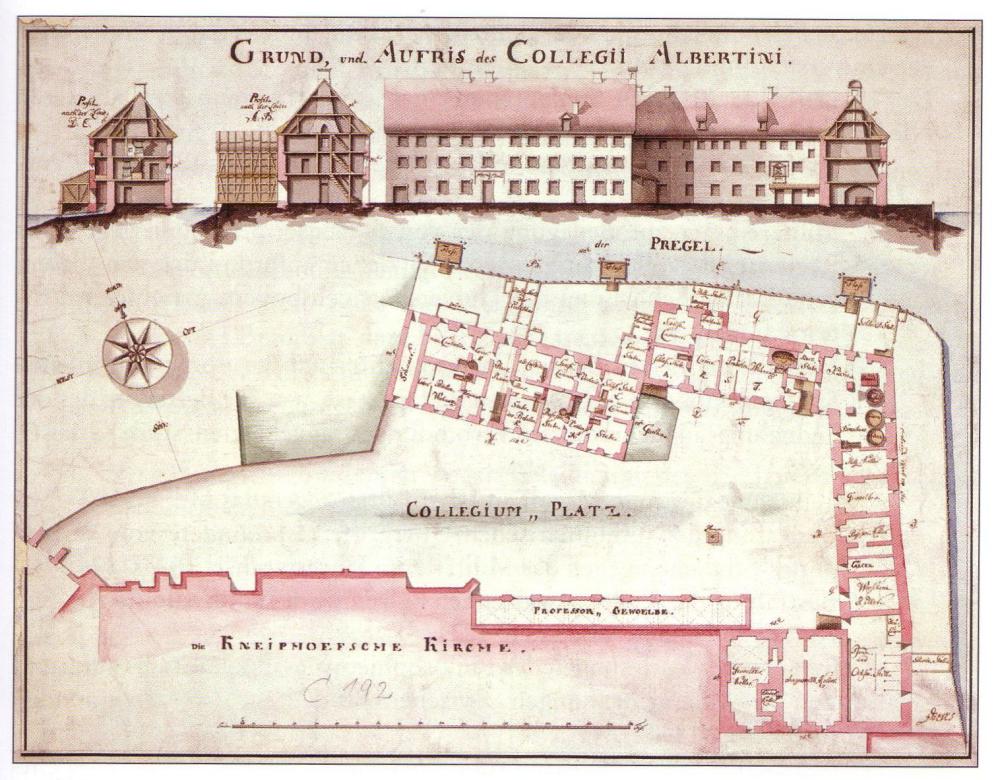

Fig. 1b. Seal of the Königsberg University Albertina (creative commons)

The famous University Albertina in Königsberg was founded in 1544 as the second Protestant university after Marburg. In 1844, King Frederick William IV of Prussia (1795--1861) laid the foundation for the new main building of the Albertina -- according to plans designed by the Prussian architect Friedrich August Stüler (1800--1865); the building in Neo-Renaissance style was inaugurated in 1862.

In 1809/1810, in the middle of the Napoleonic wars, the Prussian government, King Wilhelm III., wanted to build an observatory in the East Prussian capital Königsberg. At that time Wilhelm von Humboldt (1767--1835) in Prussia promoted extensive reforms in education and administration. Young scientists got the opportunity in universities and academies.

Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (1784--1846), active in Lilienthal Observatory, got the call as professor in 1809, and arrived on May 11, 1810 in Königsberg.

On the financial outlay, Bessel remarked:

"Es kann sonderbar scheinen, dass in den jetzigen Zeiten so viel an eine Sternwarte verwandt wird; allein die Zeiten, wo das Militair alles wegnahm, sind vorbei, und so wird denn das lebhafte Interesse an wissenschaftlichen Sachen erklärlicher. Unsere Regierung ist in dieser Hinsicht allen anderen ein Muster." ("It may seem strange that in the present times so much is spent on an observatory; but the times when the military took everything away are over, and so the lively interest in scientific things becomes more explainable. Our government is a model for all others in this respect.")

(Königlich Preußische Akademie der Wissenschaften (ed.): Briefwechsel zwischen Gauss und Bessel. Leipzig 1880, p. 144, Letter from Bessel to Gauß dated 10 March 1811).

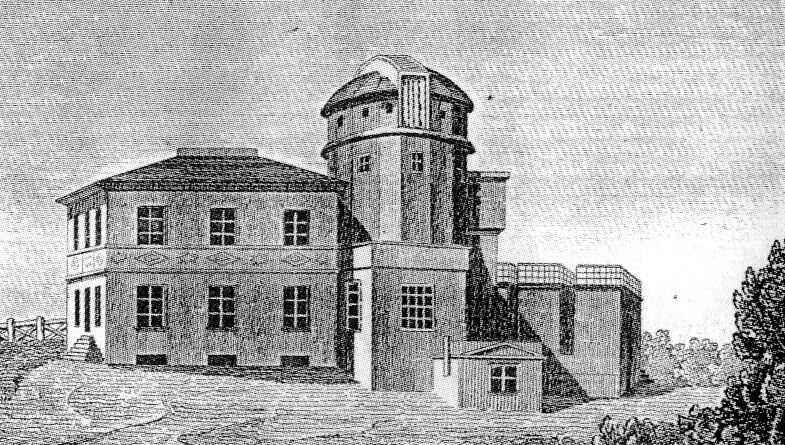

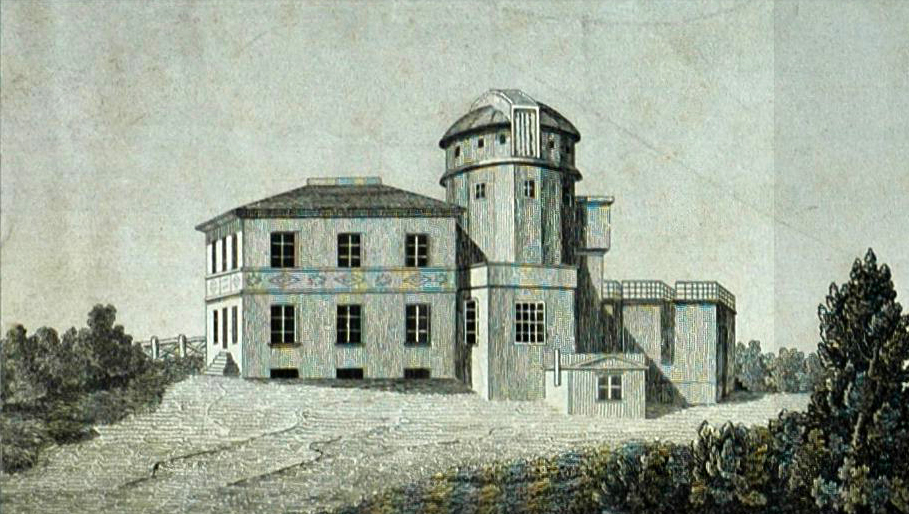

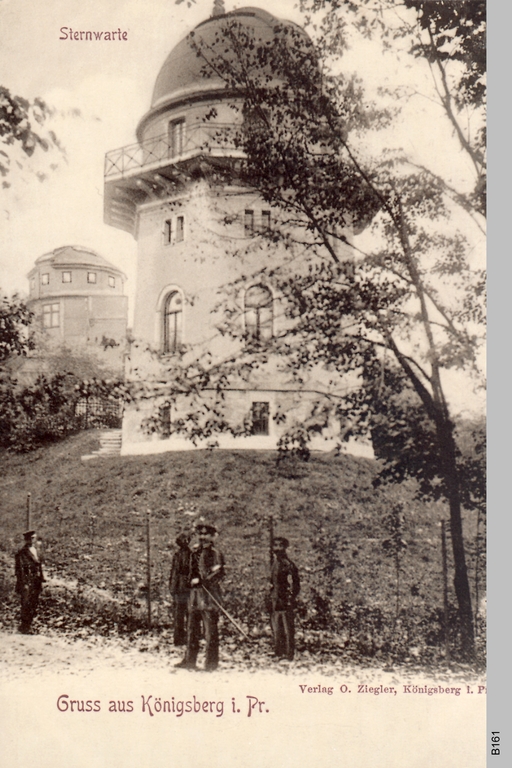

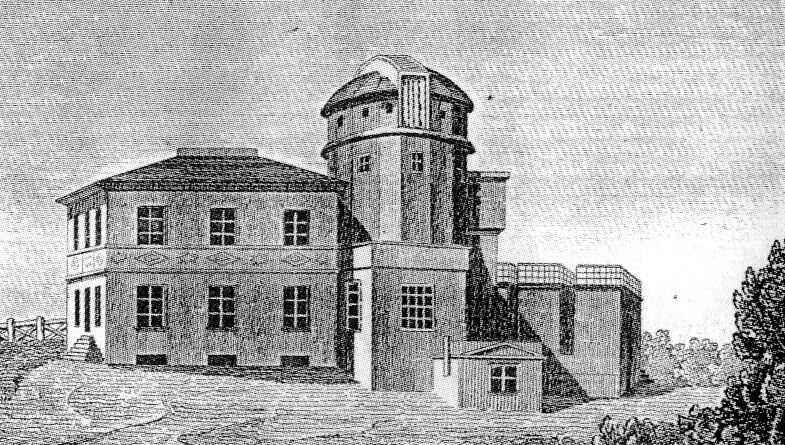

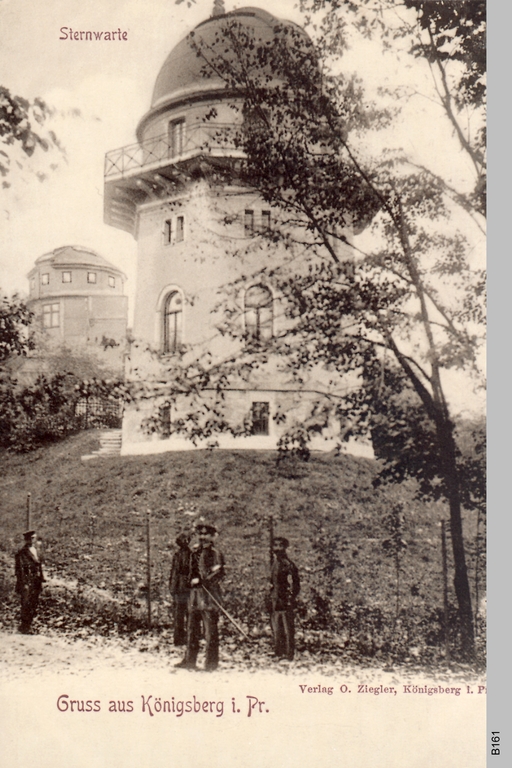

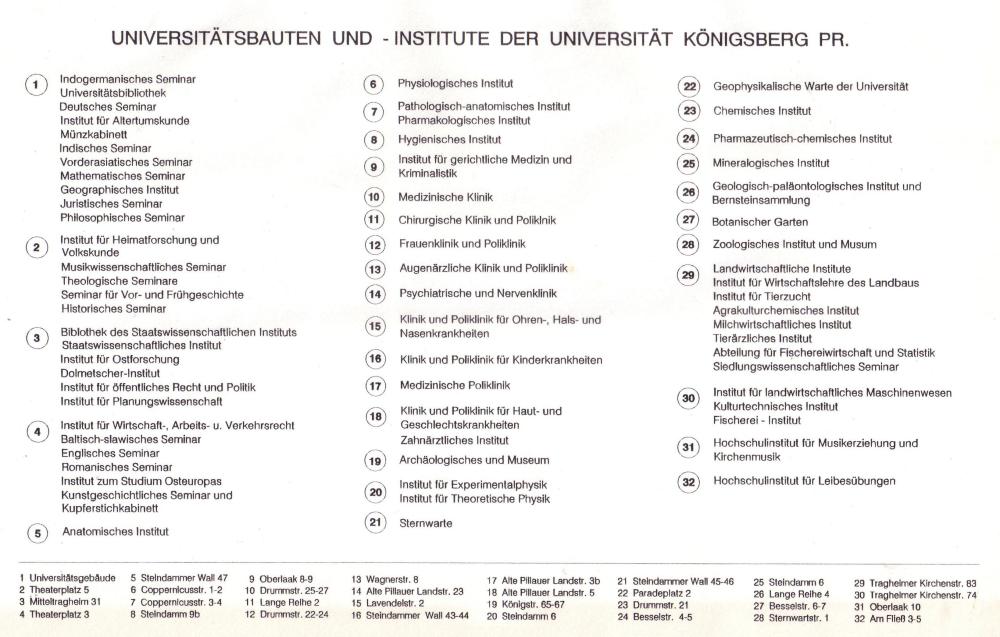

Fig. 2a. Königsberg Observatory with heliometer tower, around 1830 (Wikipedia)

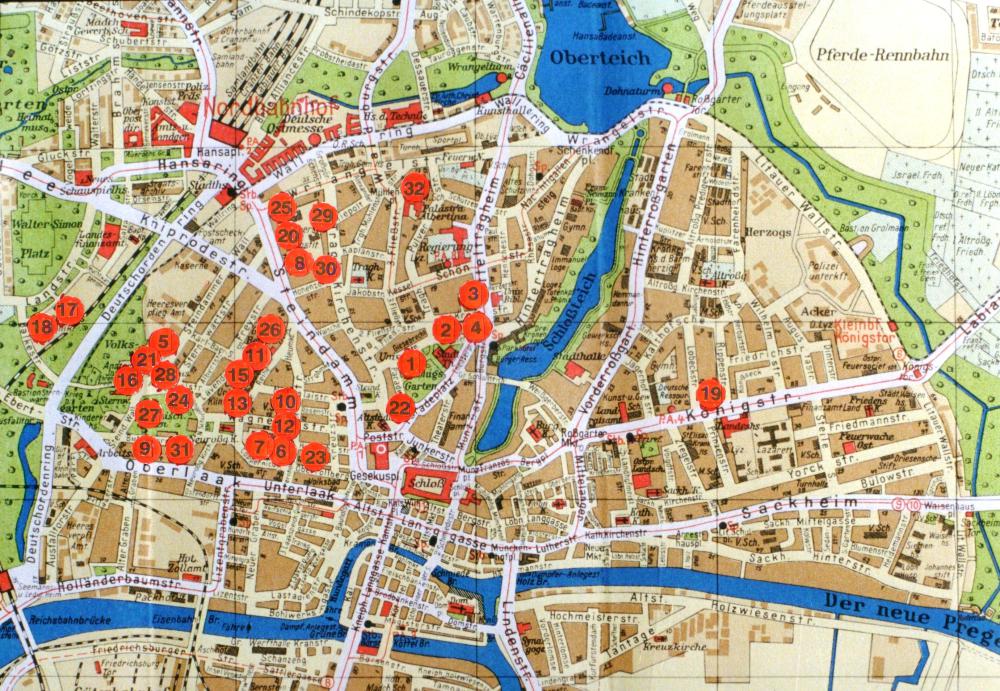

In addition to the academic teaching, the first focus of Bessel’s work was building an observatory. He chose the site on the former fortifications (Butterberg) in the Northwest of the city. Then he designed a plan for the architecture, which he had to defend against the different plans of the Berlin government. On November 10, 1813, he was able to move into the completed observatory.

The first equipment consisted mainly of used instruments, which the Prussian state acquired in 1809 from the estate of Friedrich von Hahn (1742--1805) of Remplin Observatory. By procurement of the director of the Berlin Observatory, Johann Elert Bode (1747--1826), the instruments were donated to the new Observatory Königsberg (1810):

- 2-inch-Cary circle (25-inch diameter of the circle, focal length 33-inch) is used for meridian observations; this instrument is now in the Deutsches Museum Munich - an instrument allowing the highest precision in determining the positions of the stars,

- 2.7-inch-"Mittagsfernrohr" (4-inch-"Meridian/Transit telescope"), made by Dollond (1.3m focal length), today in Breslau - an instrument allowing the highest precision in determining the positions of the stars,

- Comet seeker, 1-inch-"equatorial telescope" (33cm short focal length telescope),

- 12’’ and 6’’ mirror-based sextants (reflecting circle)

- Pendulum clock for sidereal time.

Because the large instruments were not yet available, Bessel began evaluating the observations of the British astronomer James Bradley (1692--1762) and created a star catalogue with 3,000 stars. The fundamental work entitled "Fundamenta astronomiae" was published in 1818.

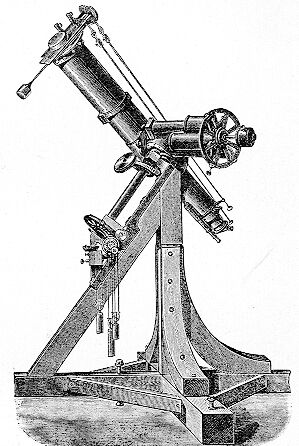

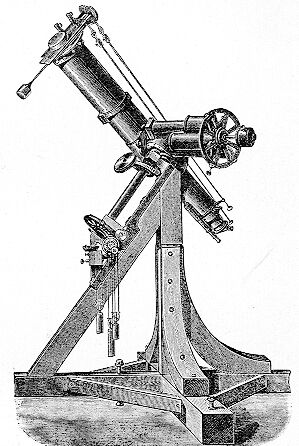

Fig. 2b. Heliometer of Königsberg Observatory, 1829 (Wikipedia)

- 13-inch-Refractor (33cm focal length), (1819) - this was the main instrument of the observatory

- Meridian circle with a Fraunhofer objective, made by Georg von Reichenbach of Munich, (1818/19)

- Heliometer, made by Utzschneider & Fraunhofer, Georg Merz & Franz Joseph Mahler of Munich (1829)

- Meridian circle, Adolf Repsold of Hamburg (1841).

The Bessel zone observations with the meridian circle (positions of 30,000 stars) later found their continuation in the famous Bonner Durchmusterung of Friedrich Wilhelm August Argelander (1799--1875), who was Bessel’s assistant from 1820 to 1823 -- in the early days of zone observation.

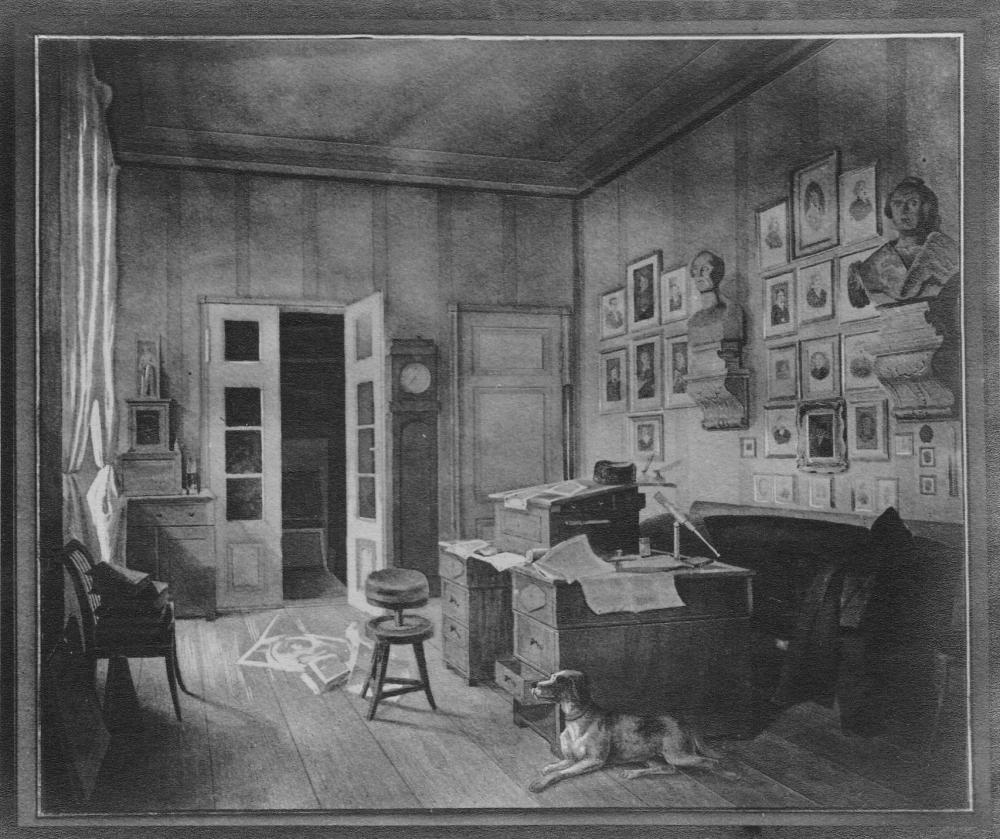

Fig. 3a. Bessel’s study in Königsberg Observatory (Daguerreotype, estate of the astronomer Fritz Hinderer, Creative Commons)

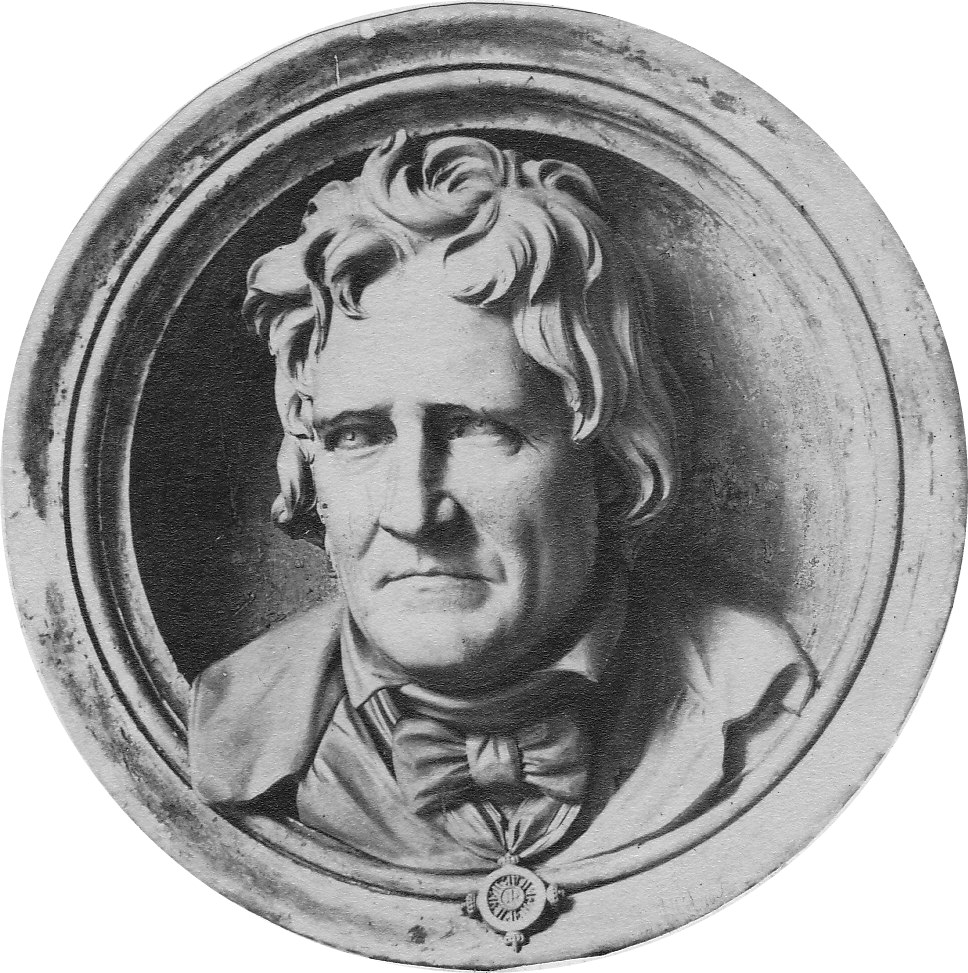

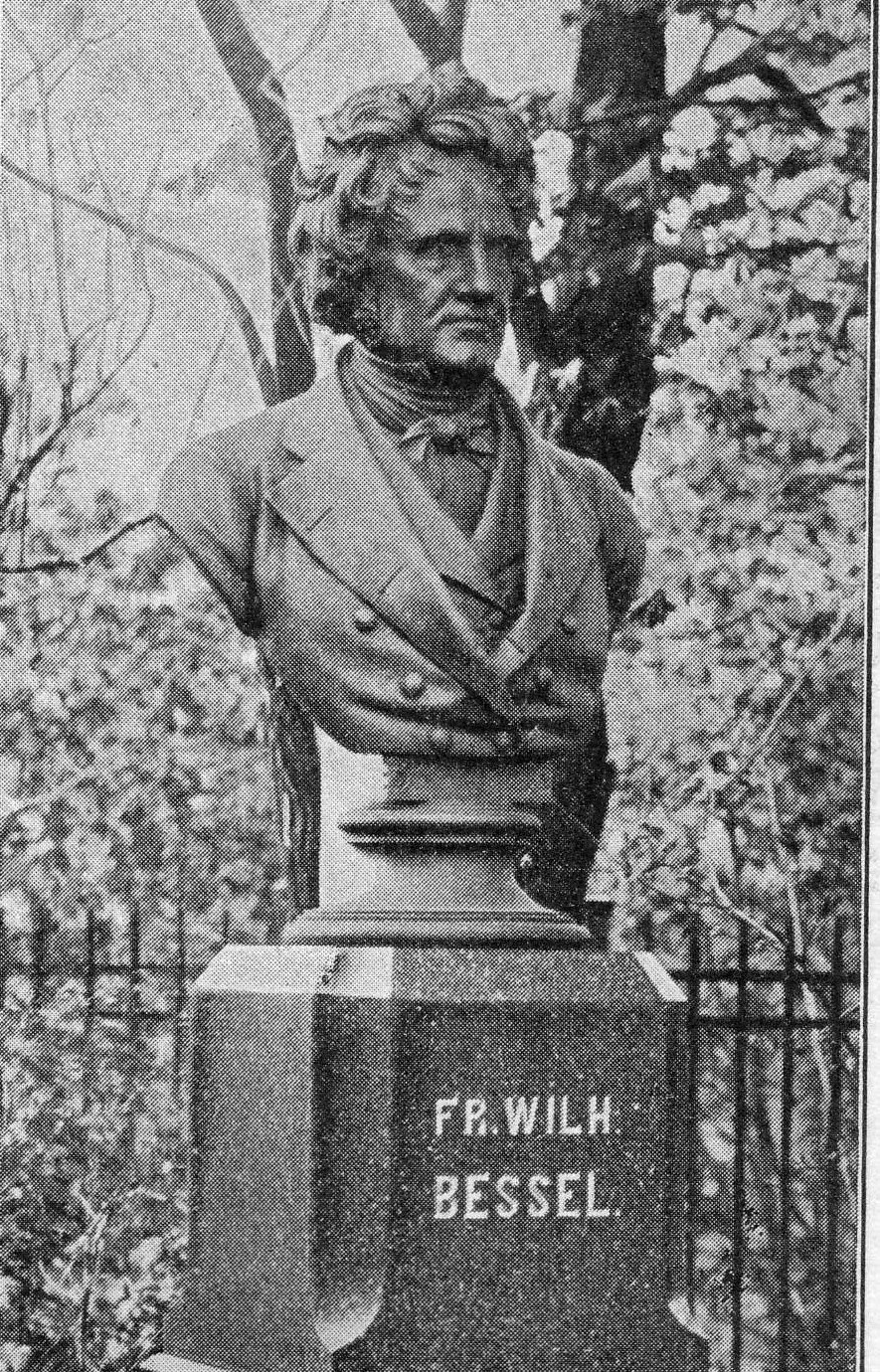

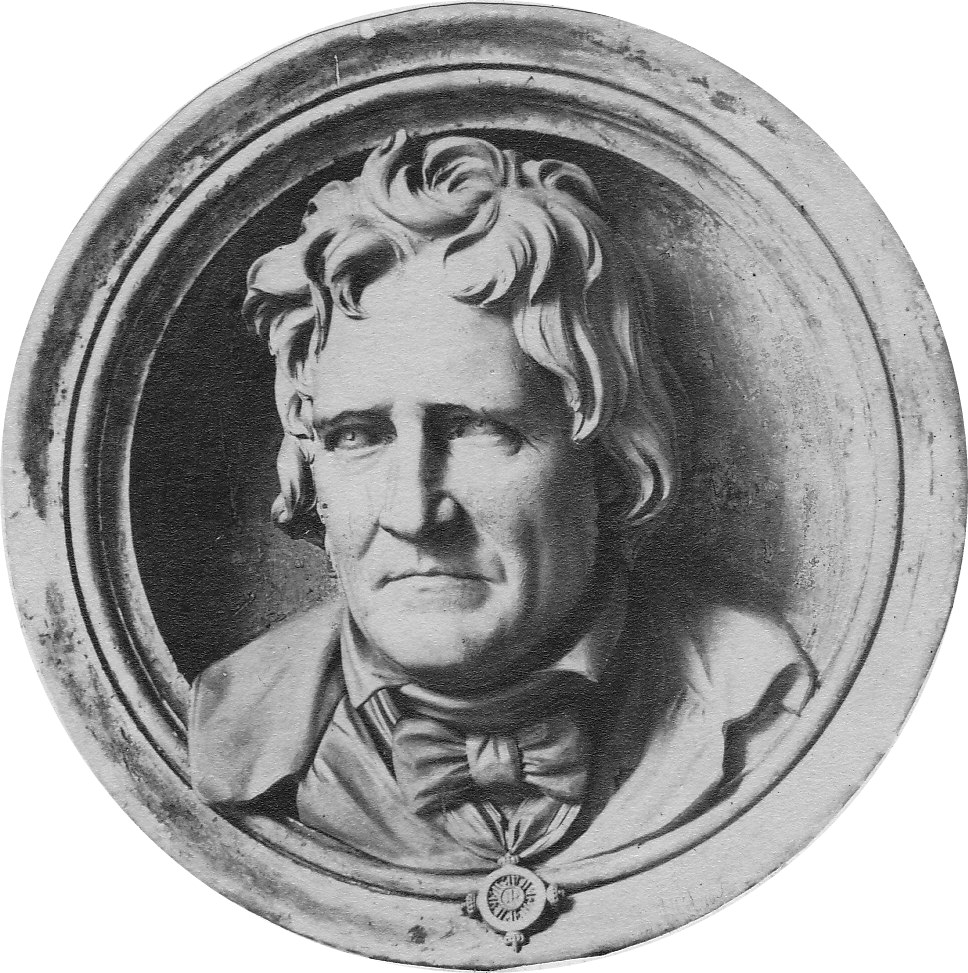

Fig. 3b. Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (1784--1846), relief by Rudolf Siemering, 1900 (Creative Commons)

The Royal Königsberg Observatory was an astronomical research institute affiliated to the Albertus University of Königsberg (1544 to 1946). Bessel trained scholars from all over Europe to become practical astronomers. Many of them were later directors of astronomical institutions in Europe.

Königsberg became one of the leading research centers of astronomy in Europe through Bessel’s work. The highlight was: Bessel was the first astronomer to determine the exact distance of a fixed star.

Fig. 4a. Karl Hermann von Struve (1854--1920) (Creative Commons)

Fig. 4b. Eduard Luther (1816--1887) (Creative Commons)

Also after Bessel famous astronomers like Friedrich Wilhelm Argelander, Arthur Auwers (1838--1915), Karl Hermann von Struve (1854--1920) and Eduard Luther (1816--1887) worked there.

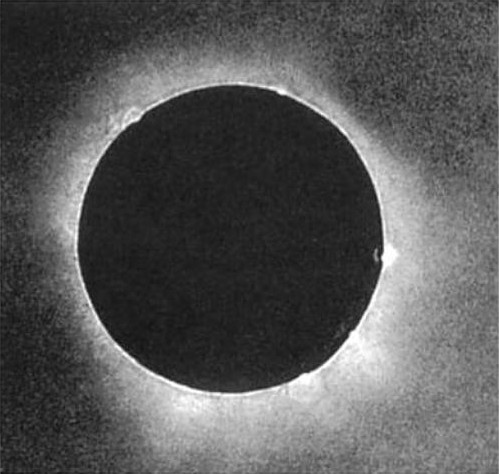

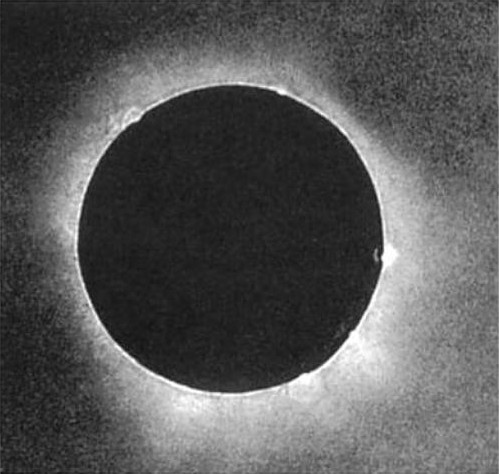

Fig. 5. First photograph of a total solar eclipse (1851) in Königsberg Observatory (daguerreotype by Julius Berkowski on July 28, 1851)

Another highlight of Königsberg Observatory was the first photograph of a total solar eclipse, taken as a daguerreotype by Julius Berkowski on July 28, 1851.

Fig. 6. Astronomical Bastion in Kaliningrad, place of Königsberg Observatory (CC3, Alexander Grebenkov)

The air raids on Königsberg in August 1944 severely damaged the observatory as well as numerous other university buildings.

Russia today tries to keep the memory of the names and the remarkable achievements of the famous mostly German astronomers alive in the Russian city of Kaliningrad.

History

Fig. 7. Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (1784-1846), painting by Christian Albrecht Jensen, 1846 (Creative Commons)

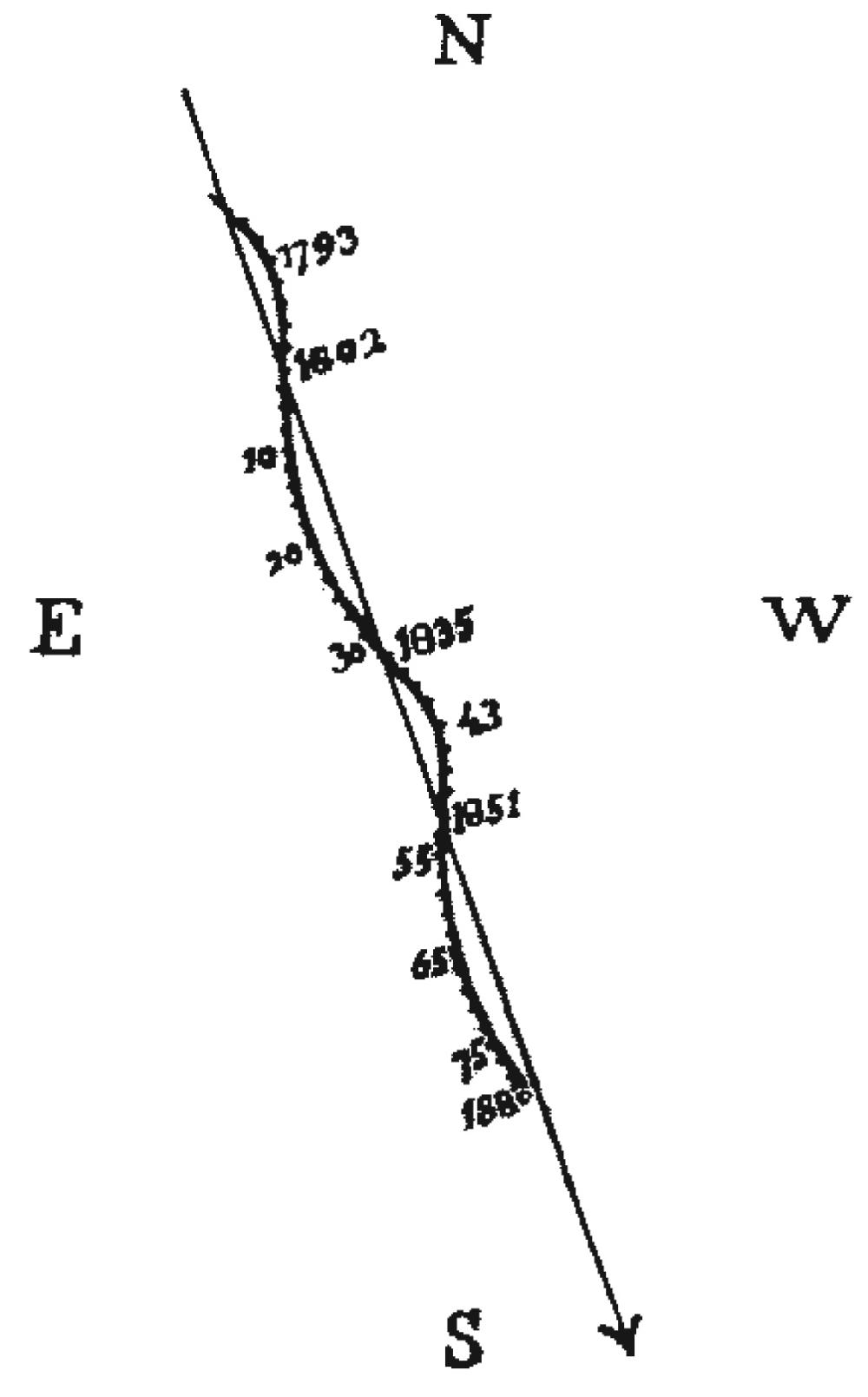

Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (1784--1846) succeeded in 1838 in measuring the first fixed star parallax. Alreday in 1802, Johann Hieronymus Schroeter (1745--1816) estimated the upper limit of the parallax for the nearest stars to be quite reliable at 0.75 seconds of arc. Bessel realized that the parallax he wanted had to be well below 1’’. He also knew that the accuracy of the instruments of that time, like a meridian circle, was far from sufficient. Only his Fraunhofer Heliometer (1829) offered - in addition to the large Fraunhofer refractor with equatorial mounting and clockwork drive in Dorpat -- the possibility for an accurate measurement. Bessel began the series of measurements in August 1837 and finished them in October 1838. He determined the parallax value of 0.3136’’ with a mean error of 0.0202’’. In addition, Bessel had cleverly chosen the double star 61 Cygni -- the star with the largest known proper motion. As an illustrative comparison for the distance of 61 Cygni, Bessel calculated "the time which the light needs to travel this distance" to be 10.28 years.

A modern comparison: The most accurate parallax value for 61 Cygni was measured in 2015 by the Hipparcos astrometry satellite at 0.286’’, which corresponds to a distance of 11.4 light years.

An additional result was: The Copernican world view was proven by measurement, which had long been accepted by experts.

Fig. 8. Königsberg Observatory (Creative Commons)

Practically at the same time, Friedrich Georg Wilhelm von Struve (1793--1864) determined the parallax of the Vega in 1837 with his Fraunhofer refractor in Dorpat (today Tartu), Estonia, with his Fraunhofer refractor. And the Royal astronomer Thomas James Henderson (1798--1844) published in 1839 in Edinburgh a parallax value for the binary Alpha Centauri, which he had observed in 1832/1833 in Cape Town.

By the end of the 19th century, only about 60 stellar parallaxes had been obtained, using a filar micrometer. Even with modern techniques in astrometry, the limits of precise measurement is about 300 light years. With the Hipparcos satellite (launched in 1989) the the number of parallaxes and proper motions of nearby stars were increased considerably. In addition, the stellar parallaxes measured to milliarcsecond accuracy was increased a thousandfold. Hipparcos is only able to measure parallax angles for stars up to about 1,600 light-years away, a little more than one percent of the diameter of the Milky Way Galaxy.

State of preservation

Fig. 9a. Königsberg Observatory (Creative Commons)

Fig. 9b. Destroyed Königsberg Observatory (1954) (photo: Dietmar Fürst)

Königsberg Observatory was severely damaged in August 1944 and never rebuilt.

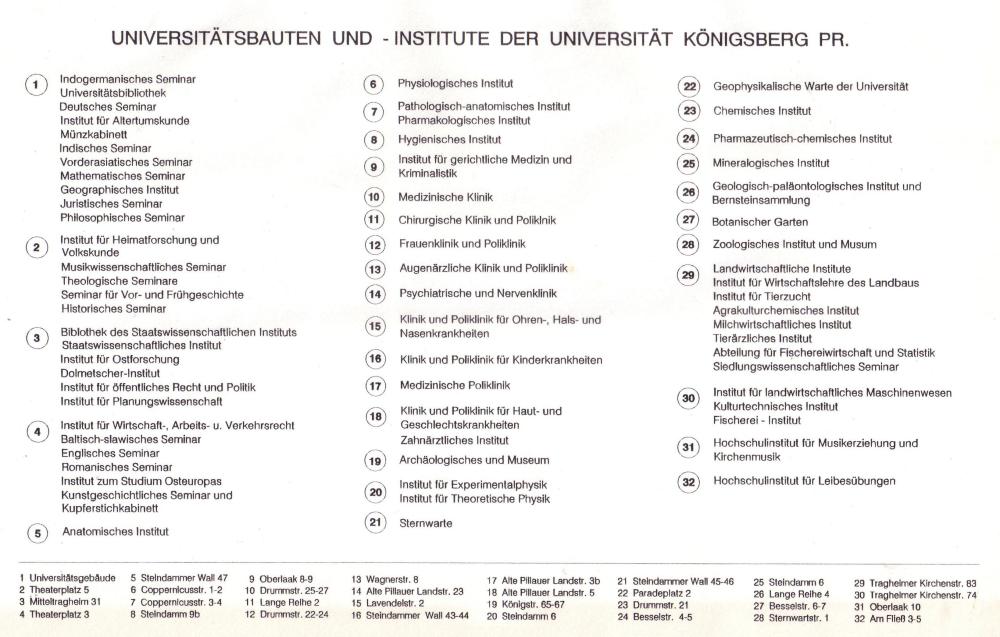

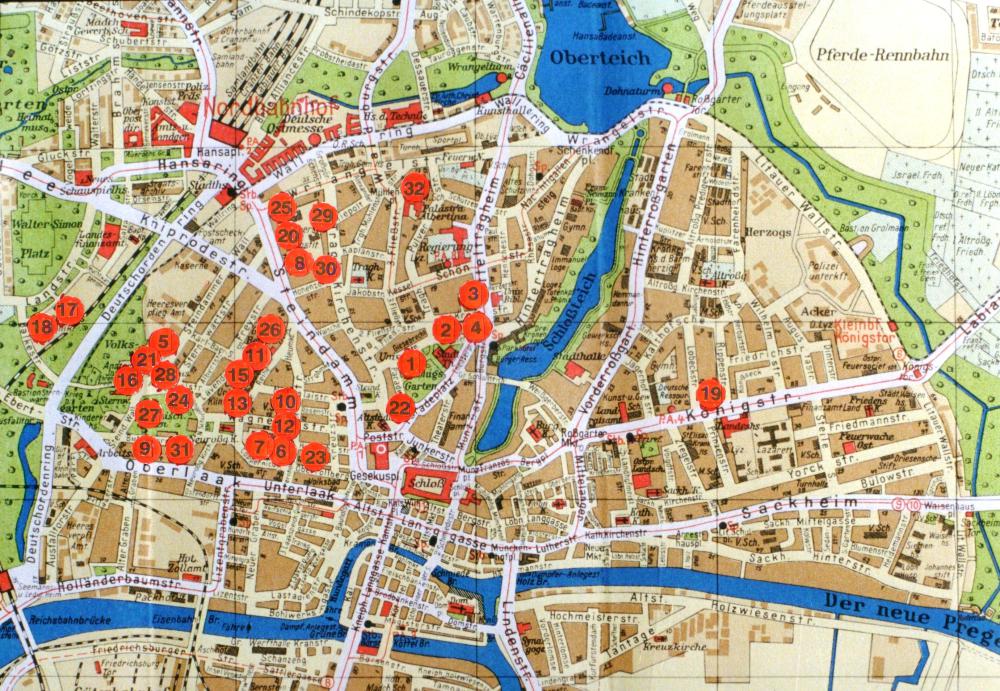

Fig. 9c. Königsberg Observatory, Nr. 21, near Astronomical Bastion, Königsberg map of 1931 (Creative Commons)

Fig. 9d. Königsberg University buildings, Observatory, Nr. 21 (Creative Commons)

Comparison with related/similar sites

Fig. 9a. Königsberg Observatory with Heliometer tower in Bessel’s time, 1830 (Creative Commons)

Königsberg Observatory (1810/13) is similar to Dorpat (today Tartu), Estonia (1810), a one dome observatory, nearly built at the same time.

Threats or potential threats

Königsberg Observatory is no longer existing, destroyed in WW II.

Present use

Königsberg Observatory is no longer existing.

Astronomical relevance today

Königsberg Observatory is no longer existing and cannot be used.

References

Bibliography (books and published articles)

- Bessel, Friedrich Wilhelm: Bestimmung der Entfernung des 61.sten Sterns des Schwans (1838), p. 65--96.

- Fürst, Dietmar: Die Gründung der Königsberger Sternwarte im Lichte der Akten des Preußischen Staates (1. Teil, bis zur Ankunft von Bessel in Königsberg). In: Acta Historica Astronomiae: Beiträge zur Astronomiegeschichte 1 (1998), p. 79-106.

- Fürst, Dietmar: Die Gründung der Königsberger Sternwarte im Lichte der Akten des Preußischen Staates (2. Teil, von der Ankunft Bessels in Königsberg bis zum Baubeginn der Sternwarte). In: Acta Historica Astronomiae: Beiträge zur Astronomiegeschichte 2 (1999), p. 145-188.

- Fürst, Dietmar: Die Gründung der Königsberger Sternwarte im Lichte der Akten des preußischen Staates. (3. Teil: Die Baugeschichte der Sternwarte) In: Acta Historica Astronomiae: Beiträge zur Astronomiegeschichte 3 (2000), p. 22-67.

- Fürst, Dietmar: Die Geschichte des Heliometers der Sternwarte Königsberg. In: Beiträge zur Astronomiegeschichte, vol. 6 (2003), p. 90-136.

- Fürst, Dietmar: ├äußerungen von Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel in seinen Briefen über die Bedeutung der astronomischen Beobachtung und einige kritische Bemerkungen über das preußische Bildungssystem. In: Acta Historica Astronomiae: Beiträge zur Astronomiegeschichte 10 (2010), S. 218-235.

- Fürst, Dietmar: Das sich verändernde Verhältnis zwischen Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel und Johann Franz Encke - Ein Versuch der Erklärung. In: Acta Historica Astronomiae: Lebensläufe und Himmelsbahnen 52 (2014), S. 159-204.

- Fürst, Dietmar: Die Geschichte der Sternwarte Königsberg - Glanz und Untergang einer astronomischen Metropole. In: Wolfschmidt, Gudrun (ed.): Astronomie im Ostseeraum - Astronomy in the Baltic. Hamburg: tredition (Nuncius Hamburgensis; Vol. 38) 2018, p. 262-264.

- Herrmann, Dieter B.: Bessels Bibliothek an der Königsberger Sternwarte. In: Die Sterne. Band 61 (1985), p. 96-103.

- Lawrynowicz, K.: Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel 1784--1846. Aus dem Russischen übersetzt von Katja Hansen-Matyssek und Heinz Matyssek. Basel, Boston, Berlin, Birkhäuser (Vita mathematica; Bd. 9) 1995.

- Schielicke, Reinhard & Wittmann, Axel D.: "On the Berkowski daguerreotype (Königsberg, 1851 July 28): the first correctly-exposed photograph of the solar corona". In: Acta Historica Astronomiae 25 (2005), p. 128.

Links to external sites

- Gemälde von Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (1784-1846), Christian Albrecht Jensen (1846) (Wikipedia)

- Büste von Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (1784-1846), Johann Friedrich Reusch (1882) (Wikipedia)

- Kaliningrad, Astronomical Bastion (Sternwarte, Observatory), Gornaya ul. 3 (Wikipedia)

- Kaliningrad, Friedrich Bessel monument, Ul. Galitskogo

- Johann Julius Friedrich Berkowski made the first solar eclipse photograph on July 28, 1851, also using the daguerrotype process, at the Royal Observatory in Königsberg, Prussia (now Kalinigrad in Russia). Berkowski, a local daguerrotypist, observed at the Royal Observatory. A small 6-cm refracting telescope was attached to the 15.8-cm Fraunhofer heliometer and a 84-second exposure was taken shortly after the beginning of totality. (Wikipedia)

No multimedia content published

Currently there is no multimedia content published for this case study